The Middle Ages were not the ‘dark’ and somber antithesis to the Enlightenment that clichés may have us believe. It was also a time of fantasy and certainly playful humor. Now, a comedic character ubiquitous to medieval culture—the fool—is taking center stage as the subject of a Louvre exhibit in Paris titled, “Figures of the Fool,” from October 16 to February 3, 2025.

From witty jesters to lascivious buffoons, men gone mad and subversive artists who live on the margins of society, the show takes a fresh look at how this figure was regularly depicted from the 13th to the 16th century, and then again during the Romantic era. In the imaginations of those who painted, carved, and wove these figures of folly on everything from tableaux to, literally, bells and whistles, these subjects served as a canvas for exploring a world turned on its head. A mirror to the absurdity and contradictions of life that were hard to face, but important to express and attempt to understand. In the form of the fool, this was most often voiced through humor—possibly the ultimate, and only real salve to the weight of life’s troubles.

After Hyeronimus Bosch, Concert in the Egg Former Netherlands, mid XVIth century.© RMN-Grand Palais (Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille). Stéphane Maréchalle

If this all sounds like it could as easily apply to contemporary life, it’s no coincidence. The jester —inspiration for the playing card, the Joker, more on that below—has continued to capture our imaginations for many of the same reasons. The Louvre exhibit, featuring over 300 artworks from Northern Europe, sheds new light on why that may be.

Who or what exactly is the fool, as it originated in the Middle Ages? A common depiction comes from the characters described in Sebastian Brant’s Ship of Fools (1494), a hugely popular and influential, German satirical allegory. There, the fool, “plays a key role, because he is an outlet during a time of crisis in the church, and amid the mutations of a society in full upheaval, notably with the emergence of capitalism,” said Elisabeth Antoine-König, senior curator in the Department of Decorative Arts in an e-mail written in French. “The fool allows for a figurative representation of questions troubling society,” she added. Later, during the Romantic period, the fool—usually a male figure—is identified with the artist, and their struggle with inner thoughts and emotions.

The fool is “one thing and its opposite, he is the rejected marginalized figure, and the one who unites us, and bears the ridicule and anger of others,” added Antoine-König, who compares these ambivalent traits with the supervillain Joker, of DC Comics.

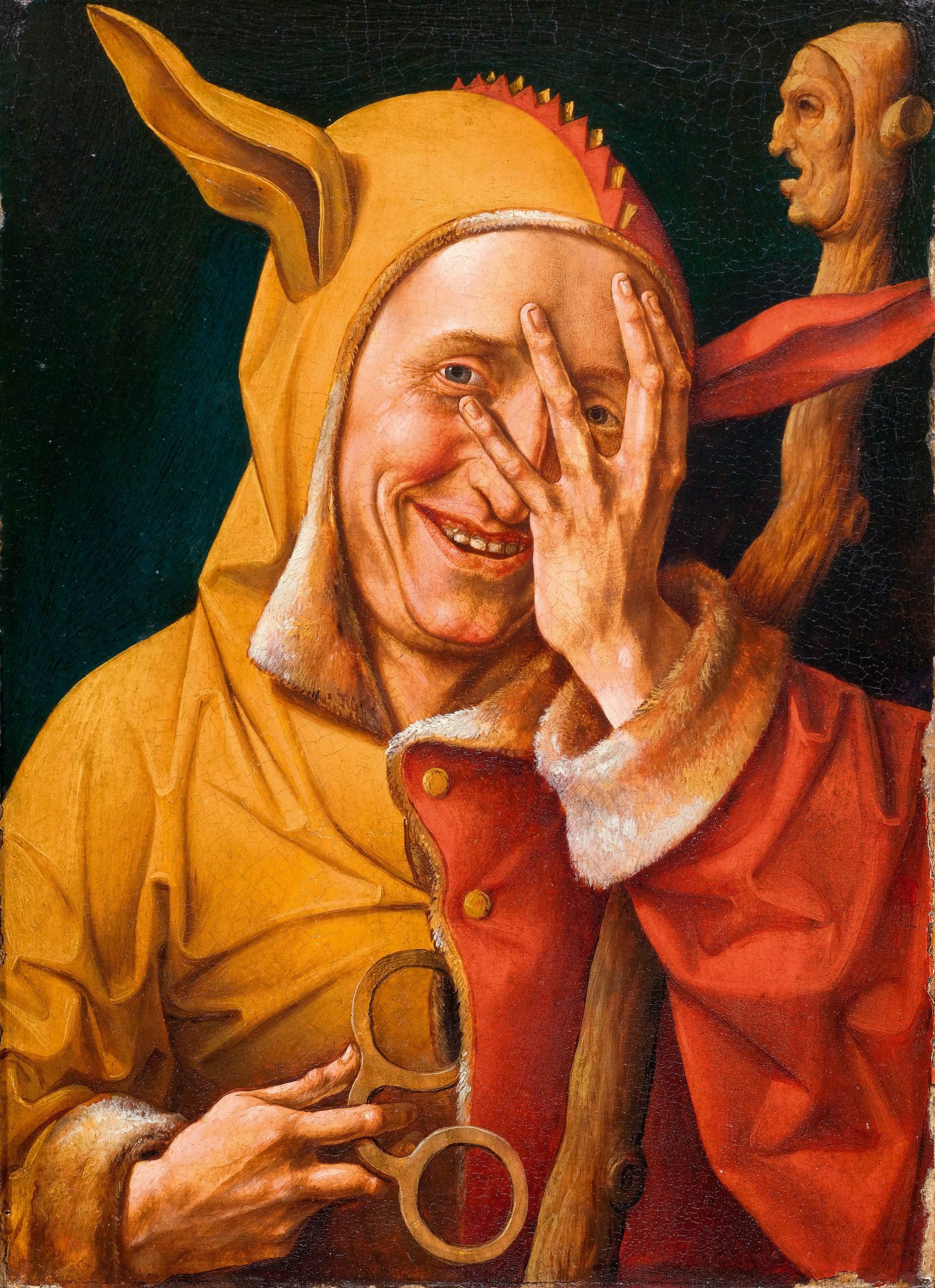

Marx Reichlich, A Jester. Tyrol (ca. 1519-1520). © Yale University Art Gallery.

By coincidence, Todd Philipps’s new film, Joker: Folie a Deux has come out at about the same time as the Louvre’s exhibit, though the latter was apparently in the making for over ten years. Far be it from the world’s largest museum to pass up a golden opportunity. The Louvre partnered with Warner Bros Pictures on a short clip promoting both endeavors. Lady Gaga, who stars in the Joker film, can be seen in the clip wandering through the Louvre halls at night, and painting a red lipstick smile over the glass protecting the Mona Lisa. From the right angle, it transforms La Joconde’s modest, soft smile, into a wide, cartoonish grin. Plus, La Joconde, as she is called in French, sounds a lot like Joker, points out the museum in a statement. Touché.

Aquamanile : Aristotle and Phyllis. South Netherlandish, (ca. 1380). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Yet as captivating and troublesome a figure as the fool still is, Antoine-König wonders whether there is still much we can learn from the fool of yesteryear, when it played a much more prominent role in social life. “I feel that the figure of the fool, as it existed in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance is lacking today, in helping us face the crises we are experiencing… During that period [13th to 16th centuries], most subjects could be interpreted in a variety of ways. Today, we reflect little on the exercise of seeing things from different angles.”

Jan Matejko, Stanczyk during a ball at the court of Queen Bona in the face of the loss of Smolensk. Krakow, (1862). © Varsovie, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie / Piotr Ligier

Antoine-König, who co-curated the Louvre exhibit with Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, also compares our current, fraught experience with digital technology and social media to the radical transformations brought by the invention of the printer. “But who is helping us manage this turning point?” She asks. “In the artworks we are exhibiting, the artists, and through them, the people of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, allowed themselves to laugh about a lot of particularly difficult things.”