Wendy Watriss, Vietnam Veterans Day in Texas. Dan Jordan, Vietnam War veteran, and his son Chad Jordan, after a speech about Agent Orange outside the Texas State Capitol, Austin, Texas, 1981. From the Agent Orange series.

Courtesy of the artist.

Wendy Watriss and Fred Baldwin’s relationship with the Menil Collection goes way, way back. Dominique de Menil gave the globetrotting photojournalists a show at Rice University in 1976. Watriss and Baldwin have lived in a house on the Menil’s Houston campus since the early 1980s. Since 1983 they have been running FotoFest, one of the world’s largest recurring exhibitions of photography and photo-related work, the latest edition of which opened on March 15th. This year the city’s revered temple to modernism isn’t hosting one of the photography festival’s exhibitions, but it is honoring its founders with an exhibition surveying their politically engaged, powerfully composed, and still-vivid photos from the 1950s through the ’80s.

“They received a lifetime achievement award at the Houston Fine Arts Festival last fall, FotoFest was founded in 1983, they have a new director [Steven Evans], and it seemed like we ought to pay attention to some great artists and leaders in our own community,” Toby Kamps, the Menil’s curator of modern and contemporary art, who curated “In the Midst of Things—Fred Baldwin and Wendy Watriss,” told artnet News. “They’re both so articulate, and they’re both people who are rebels—rebels against the limitations of class and race and gender, and way ahead of their time. I think we could all learn from them.”

Wendy Watriss and Frederick C. Baldwin, Railroad Street, East Texas, 1978.

Courtesy of the artists.

The very focused presentation at the Menil consists of just 17 photos, with one or two works offering a glimpse of some of Watriss and Baldwin’s best-known series. While their pictures are firmly rooted in photojournalism, Watriss does see formal correspondences between her and Baldwin’s work, and that of the more conceptual artists featured in this year’s biennial, which is devoted to Middle Eastern artists.

“The work chosen at the Menil, even when it’s funny or ironic, has serious content,” Watriss said. “There is depth to the content, and in that respect there is a resonance with the work in FotoFest.”

The duo’s extensive projects documenting rural poverty and African-American family reunions in Texas during the late ’70s are each represented by a pair of images. At the Menil, Baldwin’s intimate snapshot of Martin Luther King resting before a 1964 speech in Savannah, Georgia, is placed next to the artist’s photo of a Ku Klux Klan rally in Reidsville, Georgia, from 1957. Two images from Watriss’s series on the Vietnam War Memorial show grieving families gathered in front of Maya Lin’s somber monument. Another, from Watriss’s groundbreaking work on the effects of Agent Orange on US soldiers, shows a Vietnam veteran holding his crying son during a rally at the Texas state capitol in Austin. Like many of Watriss and Baldwin’s most powerful images, it shows a moment of communion or relative calm, and lets historical, geographic, and political context supply the tension and drama.

“Very seminal to my work is the ‘Agent Orange’ series, and the fact that not only did that work receive a lot of attention and awards, but most importantly the work was used to actually get legislation both at the state level and then at the federal level to provide healthcare and recognition of chemical exposure as a health issue for veterans,” Watriss said. “The Texas work was really strong because we actually were immersed with those people’s lives and the different cultural frontiers of Texas, which was in a sense used by us as a microcosm to US American history and understanding our own roots as citizens of the United States after having been outside the United States for so long for much of our work.”

Wendy Watriss and Frederick C. Baldwin, Family reunion, East Texas, 1975.

Courtesy of the artists.

Collectively, the images in the Menil exhibition testify to a half-century spent documenting social upheaval in the US. Kamps worked very closely with the artists to select pieces for the show.

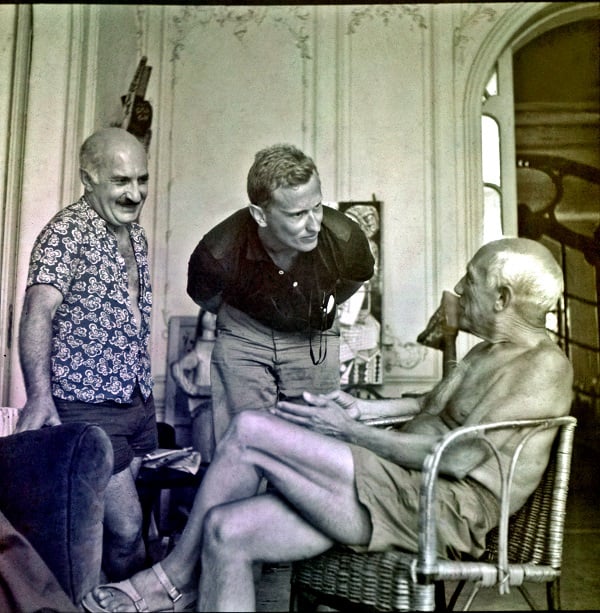

“I went over to their house, they pulled out boxes, and we started talking,” he said. “There are bodies of work—there’s the Civil Rights movement, there’s the Texas hill country, there’s East Texas family reunions, the Agent Orange work that Wendy did, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial work, then there are some early photographs of Picasso that Fred took. So we started talking about their career in terms of bodies of work. I had pretty strong opinions about individual works, but it seemed like trying to hit all the major series was important.”

Watriss agreed, citing some especially dear series of hers and Baldwin’s that were nonetheless omitted.

“Among our most important series, there are one or two pictures from each of those,” she said. “What wasn’t included that I think is very strong is Fred’s work from a place called Tiger Ridge in Georgia, that showed the poverty and conditions of white people in the 1960s, and my work from Nicaragua during the civil conflict in the early ’80s. And there are smaller essays of good work that both of us did—his work in Mexico on a huge horse ranch in northern Mexico, and some of my work in West Africa—but the show at Menil, which is very small, touches upon the particularly important series of works that we’ve done.”

The majority of the work in the exhibition is very political in nature, whether overtly or implicitly, but the inclusion of Baldwin’s two 1955 photographs of Pablo Picasso—along with a small ceramic bird sculpture by the Cubist and a facsimile of a letter Baldwin sent him—may seem anomalous. For Kamps, however, these images and artifacts are crucial to understanding Baldwin’s career and his subsequent collaborations with Watriss.

Frederick C. Baldwin, Self-portrait with Picasso, 1955/2014.

Courtesy of the artist.

“Sitting down with Fred, he told me about the Picasso mantra,” the curator recounts. “He was a college student, I think he was in his last semester at Columbia, he didn’t know what to do with his life, because of his diplomatic upbringing he was drifting around Europe. His own father died when he was young and he kind of envisioned Picasso as his imaginary father, a hero figure, fearless, charismatic, you name it. And he went on this quest to meet Picasso, and was eventually successful. Picasso lets him in and they take a couple of pictures, and Fred has a mantra which is: You have to have the dream, you have to use your imagination, you have to overcome your fear, and you have to act. And that breakthrough, the first thing he accomplished on his own, set the course—that if he used his wits, his creativity, and his courage, he could make things happen. That’s what launched this career.”

From those formative works, and Watriss’s own solo pursuits of the ’80s, the exhibition hones in on their many collaborative projects documenting periods of tumult and injustice in recent American history.

“This was really about trying to focus on them,” Kamps said. “They’ve been helping photographers all these years, and this was really to shine the light on them, and a life in art and collaboration, and a tremendous service to artists and the public.”

“In the Midst of Things—Wendy Watriss and Fred Baldwin” continues at the Menil Collection through July 6, 2014. FotoFest 2014 continues at venues throughout Houston until April 27.