New Yorker Jose Mugrabi and his sons Alberto and David illustrate how individuals with great wealth can become art market participants who influence prices. The Mugrabis have the biggest Warhol collection in the world outside of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. The count is at least 800, with some estimates higher. Jose Mugrabi was the consignor of Warhol’s Men in Her Life, which sold at $63 million.

Jose, 73 at the time of writing, is the son of Syrian Jews who ran a grocery store in Jerusalem. At the age of 16 he was sent to Bogota, Colombia, to live with an uncle and work in the fashion industry. At 22 he started a wholesale fabric business that flourished. Colombia, he says, was a dangerous place to raise children. “A little kidnapping, you have to go with a bodyguard, you have to have an armored car.” The family moved to New York.

The transition from textiles to art started in 1987, four months after Warhol’s death. Mugrabi was visiting Art Basel when he saw his first paintings by the artist. “I liked the pictures,” Jose says, “the paintings impact me. The feeling I had about the others, nothing. Then [with Warhol], I feel something.” Jose bought the four-painting Warhol version of da Vinci’s Last Supper for $144,000 each. In 2009 he estimated their value at $4 to $6 million.

The Mugrabis built their collection over 25 years. They credit their collecting model to Charles Saatchi, an English art patron turned private dealer (his story is next). But Saatchi purchased multiple works from a great many artists while the Mugrabis collect only a preferred few.

Jose’s interest lies with the Pop movement. Alberto, 42, and David, 40, are more interested in younger artists like Damien Hirst, Richard Prince, and Jeff Koons. Jose describes the family’s preferences as artists who represent what America gives the world (Warhol’s Coca-Cola), or artists that represent its commercial culture (Prince, Koons, Hirst, and Basquiat).

The family is best known for their Warhols. Beyond those, the Mugrabis own what is believed to be one of the most valuable private collections of contemporary art in the world. It includes 3,000 works; 100 or more by each of Hirst, Basquiat, George Condo, and Tom Wesselmann. Before the 2008 economic downturn, the Mugrabis estimated the value of the collection as “approaching a billion dollars.”

The family are private dealers on a massive scale. “We’re market makers,” Alberto is quoted as saying. “You cannot have an impact buying one or two pictures per artist. We want inventory; [it] gives you staying power.” In the commodities sector, an analogy would be controlling enough of the futures market in silver to be able to move the price. The Mugrabis buy and sell works directly, through dealers, and in as many as 50 auctions a year. During contemporary auction weeks in New York, the family has been known to have 30 works offered among three auction houses.

During the 2007–2009 art recession, David Mugrabi said the family did a lot more buying and much less selling. In November 2008 they acquired Warhol’s Marilyn (Twenty Times) (1962) for $3.98 million. In 2013 the painting might be worth more than $40 million. A few months later, and for under $5 million, they purchased 38 Warhols bearing images of Marilyn Monroe from Zurich dealer Bruno Bischofberger. “A down market is when you find bargains.”

In 2009 the Abu Dhabi Royal Family reportedly offered the Mugrabis “several hundred million dollars” for their 15 best Warhols, including Marilyn (Twenty Times), for the planned Abu Dhabi Guggenheim Museum. Jose reportedly countered with a price of $500 million and was turned down. Alberto has said that nearly everything in their collection is for sale. “If we don’t want to sell a picture, we ask like three times what the estimate would be.” In the Abu Dhabi case, $500 million was probably not far off the 2009 market value and a bit less than the value of the 15 in 2013.

It is accepted in the art world that the Mugrabis and one or two others account for 30 to 40 percent of all Warhol purchases at auction each year. The family attends most major evening contemporary auctions. Jose is famous for his auction uniform: blue jeans, a black T-shirt, and a baseball cap. He never bothers with an auction paddle; the auctioneer knows who and where he is. Although most important collectors bid from the privacy of an auction skybox or via telephone, the Mugrabis want to be seen as involved when a Warhol comes up. They want a visible bidding war, not a bargain. Dealer Francis Naumann says, “What threatens them at an auction is not the presence of other aggressive bidders, but cautious bidders.” Alberto said, “If it’s good for Christie’s and Sotheby’s, it’s good for us.”

Northern California art dealer Richard Polsky says that in 2006 he consigned a Warhol Flower painting. “The estimate was $1 million, but the Sotheby’s auctioneer made it clear that the Mugrabis would be in the audience and would like to see it get $1.5 million. And that was almost exactly what it ended up selling for.” The Mugrabis apparently bid until Flower reached the desired price point. Jose Mugrabi defends his efforts to prop up prices rather than seeking bargains as being in the best interest of other Warhol collectors and the market in general.

Most of their collection is stored in two warehouses, one in Newark, New Jersey, the other in a duty-free zone in Zurich. The warehouses are required not only because of the number of works, but also because some have special storage needs. For example, Damien Hirst sharks and sheep in tanks need to be dismantled and refrigerated. Unlike others who have assembled huge collections—Charles Saatchi, or Don and Mera Rubell in Miami—the Mugrabis have no plans to open a museum of their own.

The family’s influence is such that an artist or art trend is sometimes described simply as “That was bought by the Mugrabis,” or “The Mugrabis did not want it.” Because of the number of times Warhols appear at auction, his prices have become, according to The Economist, a bellwether for the art market, the Dow Jones index for contemporary art prices. This raises the question, What happens if the Mugrabis, for whatever reason, decide to dump Warhol, or Hirst, or Basquiat, or one of their other artists-held-inbulk, and the word becomes “The Mugrabis are selling”? Would that shake confidence in the entire contemporary art market? Would other Warhol collectors-in-bulk—Peter Brant or S.I. Newhouse, for example—also bail because no one wanted to be last out the door?

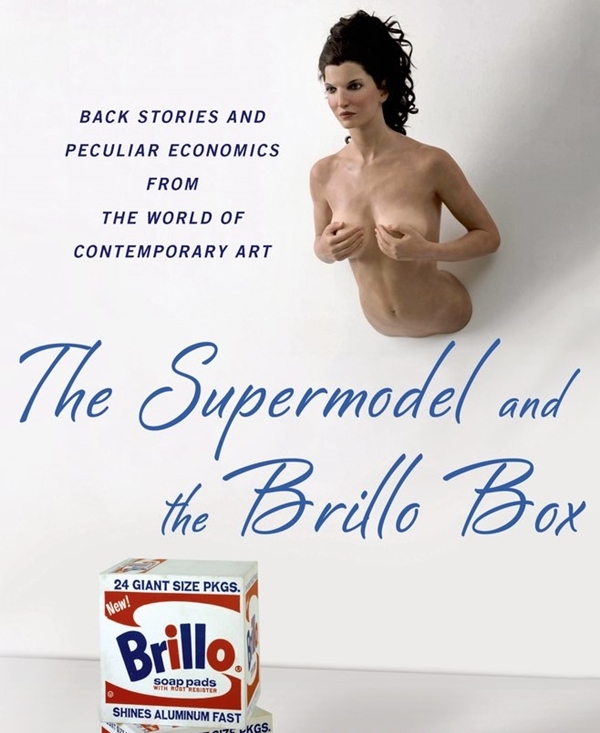

Excerpted from The Supermodel and the Brillo Box, by Don Thompson. Copyright © 2014 by the author and reprinted by permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.