Season three of Netflix’s The Crown kicked off this past Sunday, steeped in tales of espionage and intrigue lurking behind palace doors. There’s a surprising focus on art throughout the first episode, which centers on the real-life figure of Anthony Blunt, who functioned under the guise of chief curator to the Royal Collection—all while truly serving as a Soviet spy.

From the outset, the season opener is rife with the sense of paranoia over Soviet intervention that permeated royal dealings beginning in 1964, when Harold Wilson—long suspected, but never confirmed, to be a KGB spy—was elected Prime Minister to lead the Labour Party in forming a new government.

Yet, while whisperings about Wilson abounded, the suspicion was ultimately misdirected. That same year, it was Anthony Blunt who was revealed as the true Soviet sympathizer; he had been providing intelligence to the Soviets (passing along an estimated 1,771 documents throughout WWII) since long before Queen Elizabeth even ascended to the throne.

Beginning in 1945, and for nearly the next twenty years, Blunt hid in plain sight in his role as Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, a responsibility that required him to care for the vast number of artworks in the Royal Collection. His hiring is, in itself, shrouded in conspiracy theories. The most prominent of these speculates that Blunt’s appointment was made in exchange for a secret mission he conducted to Germany following the Nazi surrender, with the goal of retrieving a stash of letters purported to hold incriminating information on the King’s brother, the Duke of Windsor.

While he may have been a spy, Blunt wasn’t faking his genuine passion for the arts, and he excelled in his position at Buckingham Palace and beyond. Alongside his 1945 curatorial appointment to the Royal Collection, he was also named Director of London’s Courtauld Institute of Art in that year, and is credited for having developed the organization into the world-renowned institution it is today. Moreover, he spearheaded the groundbreaking implementation of the Queen’s Gallery, which opened in 1961 to allow public access to the Royal Collection.

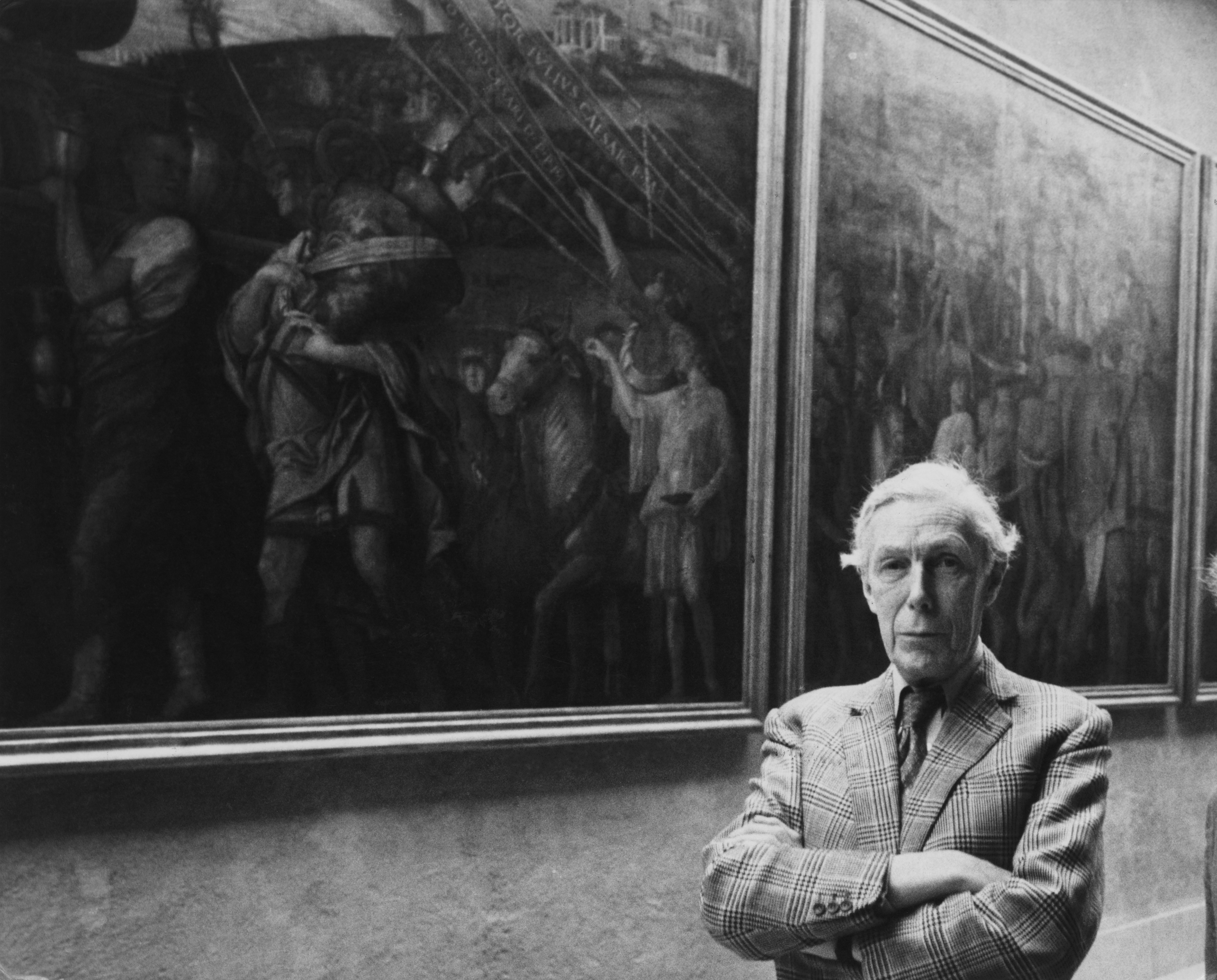

1958: Sir Anthony Blunt and Princess Margaret examining a detail on an antique trunk in the Lee Collection of the Courtauld Institute of Art. (Photo by Edward Miller/Keystone/Getty Images)

Blunt had a special affection for Baroque art, citing Nicolas Poussin and Pietro da Cortona as two of his favorite artists. He curated a Poussin retrospective at the Louvre in 1960—the artist’s first at the iconic museum—and composed a monograph on the artist’s work, now considered by academics to be the most significant text on Poussin to date.

Though mostly factually accurate, The Crown‘s season opener glaringly overlooks how the high-stakes incident unfolded in real life.

A postscript following the episode informs the audience that after the Queen was made aware of Blunt’s treasonous acts, she not only granted full immunity, but also allowed him to maintain his knighthood (which he had been bestowed in 1954), in addition to remaining in his high-profile curatorial post until his retirement in 1972.

While all true, this omits what came a bit later, none of which was good for Blunt. In 1979, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher publicly outed Blunt in the House of Commons, exposing him as a traitor, and setting off a chain reaction that saw the Queen strip him of his knighthood.

Blunt died of a heart attack in 1983, having spent the final four years of his life in disgrace. Despite this, his unwavering commitment to art remained steadfast throughout. Though he was said to have considered suicide on multiple occasions, Blunt nevertheless held on in order to complete his final project: a book on Baroque architect Pietro da Cortona.