I have, on my desktop at home, a folder called “John Berger Letters” full of unsent fan letters to John Berger.

I had been failing to write him a letter for about two years. I had questions for him about his life and work. As is true of one’s idols, I knew that they were actually questions I had about myself, and I never came up with a way to make them sound like they weren’t.

Nothing seemed good enough. And I don’t know what will seem good enough now, after he passed on Monday, at the age of 90.

Plenty of good obituaries have been written about him already. Elsewhere, I’ve already written quite a bit about both the strengths and the weaknesses of his example as a guide for the present (in “Ways of Seeing Instagram” and “The Work of Art in the Age of… Something,” respectively).

Here, I’ll just try to mention a couple of the questions he leaves behind.

The combination of death and celebrity usually inspires an outpouring of unction. Berger was a beloved figure, even by his critics—though at the same time, he doesn’t quite seem to fit in any neat box, which is how I prefer to remember him.

Upon the release in 1972 of the TV show Ways of Seeing—his pioneering, Marxist-feminist introduction to visual culture—the Guardian’s critic, Norbert Lynton, accused him of debasing the classics: “I often cannot believe Berger… it is clear from his writings that he is a sensitive man and in many ways a wise one, and that he is willing to lie about art to make his political points.”

The line was repeated in the same paper’s obit this week, the author seeming to approve of it, considering Berger, for all his success, a case of wasted potential: “how perceptive he could have been as a critic had he not been so prescriptive.”

This is the classic rap on Berger: great writer, don’t you know; shame about all that stuff concerning human liberation.

At the same time, from the view of the academy, he was seen as too sentimental, unsystematic, and conservative in his tastes at a time when Conceptualism was considered the privileged path of radical art.

In a wide-ranging 2002 essay in the London Review of Books responding to Berger’s Selected Essays, Peter Wollen accused him of imagining art only in “conventionally optical terms,” to such an extent that “much of the art of the 20th century has passed him by.”

Berger was, in other words, thought by one camp to be mutilating tradition, and to be too reverent towards it by the other.

Ways of Seeing itself reflects this tension internally. It is, famously, a celebration of modern media’s ability to transform perception. At the same time, it shows an almost prophetic faith in the power of Old Masters like Hals and Rubens as artists whose “ways of seeing” pushed against the ruling ideas of their age.

Thus, Ways of Seeing, a classic attack on traditional art and an influence on the emergent field of cultural studies, also happens to have been an amazing popular ambassador for that same tradition, making art history seem astoundingly relevant.

In essence, the series looked at once forward to a media-smart future and back to a romantic past (a strange conjunction mirrored, biographically, by the fact that his ascent to media personality coincided closely with a move to small-town Switzerland and an increasing interest in rural life).

A second weird thing about John Berger: there are very few popular art critics who are less influential for their actual opinions about art. Even Berger’s romantic-socialist politics are less divisive, perhaps, than his eclectic taste.

He acknowledges this himself, in a review, written a few years ago about his friend, the Czech painter Rostislav Kunovsky:

Journalists in the world press occasionally refer to me as one of the most influential voices writing about the visual arts. Yet I’ve never been able to influence any gallery or exhibition curator to do anything about Kunovsky’s work. For the investment and promotion circuits I have no voice. So be it.

Kunovsky, indeed, is so obscure that Berger was obliged to imagine a gallery show for himself to review, complete with an imaginary performance by Tom Waits!

Rostislav Kunovsky, Fenêtres Lettres (2011). Image courtesy www.kunovsky.com.

His taste is tough to follow. In the ‘60s, he wrote a useful little book (important to me) on an icon, The Success and Failure of Picasso, only to follow it up with Art and Revolution, a serious study of the Soviet artist Ernst Neizvestny, who is now often considered rearguard.

Reading the recent collection of his reviews, Portraits, you are struck by an eccentric constellation of subjects, as well as the way that monographic considerations overspill the form in the directions of both literature and polemic. It begins with a lyrical and philosophical essay on the Chauvet cave painters, and ends with a tribute to the (again obscure) Palestinian artist Randah Mdah (b. 1983), which doubles as a blistering reflection on conditions of life under occupation.

Randah Mdah, Puppet Theater (2008). Image courtesy randamdah.blogspot.com.

Berger’s eclectic temperament is lovable in itself. His writing is so charismatic that you can forgive him his blind spots and soft spots alike.

But there’s also a method to all this. Berger was not just unconcerned with the art critic’s traditional role of policing a canon of Good Taste—he actually thought that it reduced what art could be. Indeed, he didn’t even like being called a “critic,” saying the term “suggests somebody deciding how many marks out of 20 to give.”

In Ways of Seeing, he drew a sharp line between “a total approach to art which attempts to relate it to every aspect of experience” (his own), “and the esoteric approach of a few specialized experts who are the clerks of the nostalgia of a ruling class in decline.”

What his detractors take as his bad or eccentric taste is just a reflection of this: weighed against the average critic, he’s much less precious about questions of taste, and much more interested in the human stories that exist through and around works of art.

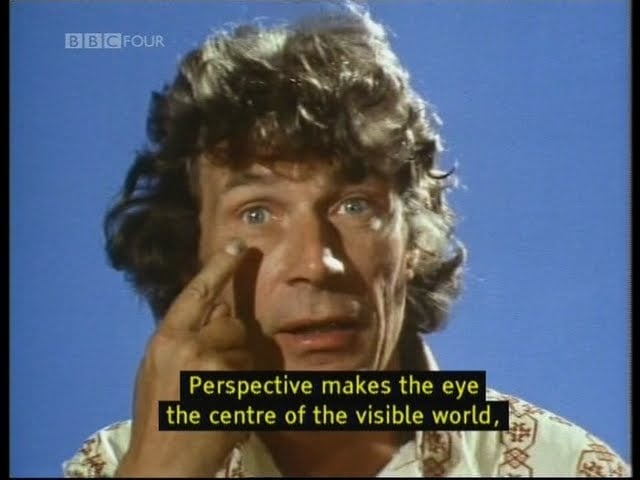

Some of this is clouded by the fact that, in Ways of Seeing, his exemplars are conventionally respected museum masterpieces. But consider this example from the second episode of Ways of Seeing—the most famous one, on the “male gaze” in art history—which is all the more powerful because it is not spoken by Berger himself: its presence reflects his will not just to express his own opinion on art, but to understand how art might function for others.

That episode concludes with a panel of women talking about their experiences of objectification and self-scrutiny. The documentary gives the last word, however, to a woman who abruptly turns the conversation deep into art history, to a detail of a lesser-known Renaissance painting, The Allegory of Good Government (1338-39) by Sienese artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti:

There are some paintings, I think at this moment of one in particular, where there is a woman wearing a garment… that is so loose, so comfortable, so easy, and it is my idea that it is very much a picture of what a picture for women might be like… It’s a fresco, it’s very, very old. It’s a picture of a woman who is supposed to represent Peace… She could be one of the liberated, or trying to be liberated, young women today. She is at ease, she is relaxed, she is not playing any part at all. She is able to combine pleasure with thought and with dreaming, and she might spring into action at any moment. For me, she has much, much more to do with nakedness, with the truth about oneself, than any number of nudes that I have seen.

You have to appreciate how jarring, on one level, this claim is from a strictly art-historical point of view. An image meant to make woman into allegorical symbol is read, startlingly, as an icon of women’s liberation from the male gaze.

And yet, this reading is as genuinely moving as it is strange. An obscure reference suddenly becomes activated and lit up by the present.

Ways of Seeing, and Berger in general, are not beyond criticism. Some of his formulations feel dated; some are confusing when you really try to follow them. A new-media obsessed world has meant that his reflections on technology look both prophetic and in need of an update, even as the predatory, toxic capitalism and nasty politics of the present make his humane radicalism seem more and more like a vital resource.

Berger wouldn’t want to be beyond criticism. “[F]inally, what I’ve shown and what I’ve said, like everything else that is shown or said through these means of reproduction, must be judged against your own experience”—those are the final lines of the series.

He leaves me with a desktop full of unanswered questions. How did he resolve the flexibility of his democratic approach to taste with his redemptive claims for artistic greats? Were the latter, in the end, just examples of art-historical storytelling?

But the point is—and this is what I really think everyone who is an advocate for art can learn from him—is that he made you want to ask these questions.

Through the steadiness of his convictions, through the humanity that filled everything he wrote, through the force of his example as someone who was at ease with being non-conformist, he made the questions of art seem worth grappling with as part of grappling with the questions of the world we live in. That is beyond reproach.