Toys are loaded with emotion. These playthings reveal something about society; Barbie, for example, may pass on an unrealistic bodily ideal to a young child. A soft bear, on the other hand, may begin to teach a child about care and compassion. And in the quirks of handmade toys, something is revealed about the psychology of their maker.

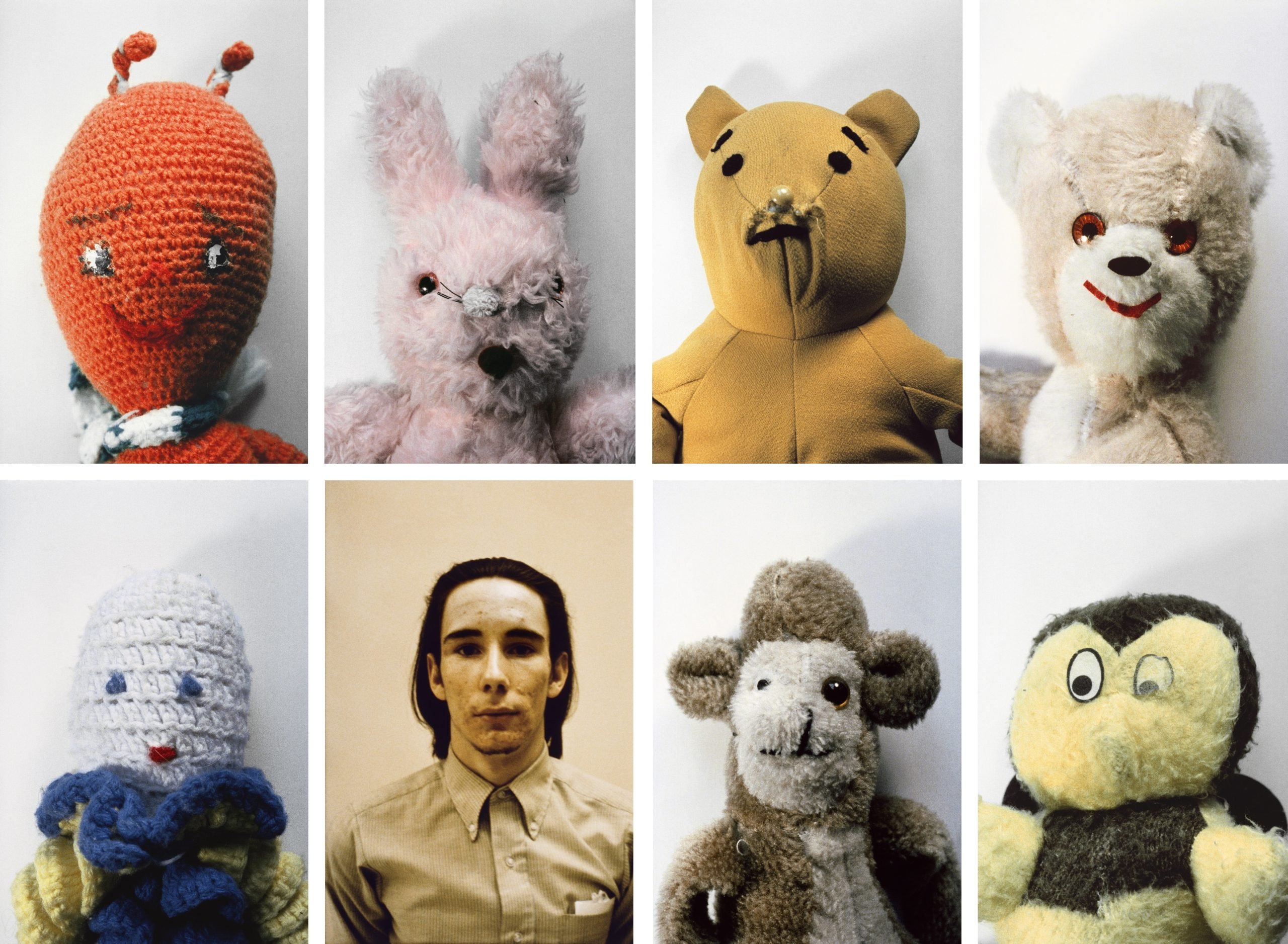

This was of particular interest to conceptual artist Mike Kelley, whose posthumous touring exhibition “Ghost and Spirit” opened last month at Tate Modern. Several key works use second-hand toys: there are bears, bunnies, and monkeys sourced in thrift stores, and many appear to have been loved to the point of near destruction. The American artist described toys as “the adult’s perfect model of a child,” implying the expectations of purity and cuteness that are often projected onto young people. Kelley wanted to talk about the darker side of childhood, which can be full of trauma and fear. His toys addressed the difficulties of early life, sometimes shown in a mass huddle together, as in the 1987 More Love Hours Than Can Be Repaid and the Wages of Sin. He photographed them in lifelike portraits, like the aptly titled Ahh…Youth! from 1991.

One of Kelley’s works, Eviscerated Corpse (1989), is especially chilling, featuring a tangle of gut-like toys spilling across the floor, led by a pink, soft snake with cartoon eyes. The work simultaneously evokes the playful aesthetics of youth and the violence of disemboweling, calling to mind the confusion of childhood trauma. “Dolls are designed to be projected onto as generically human,” he told BOMB magazine in 1992. “Handmade toys have a really strange presence especially when you compare them to the commercially made ones that are standardized. This is why they’re so weird, I think they are unconscious projections of the maker.”

Mike Kelley, More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and The Wages of Sin (1987). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee 89.13a-d. © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved/VAGA at ARS, NY and DACS, London 2024

Some artists have eschewed readymade toys and produced their own. Paula Rego famously made soft toys as visual material to replace human figures in some of her works. These objects were painted into images that dealt with traumatic subject matter, such as war, female genital mutilation, and human trafficking. In these intensely challenging paintings, human representatives such as toy rabbits, like in War (2003) or the puppet-like giants of Human Cargo (2007), enable viewers to bear looking at these scenes because of their single step removal from reality.

Rego’s works confront a form of evil that most people are afraid to see. In choosing toys for these unsettling and jarring works, she referenced both the brutality of the violent acts implied, and the innocence of their victims. The artist did not shy away from her own understanding of psychological darkness and was drawn to forms of twisted play. “I cut off my dolls’ fingers, all of them,” she told the White Review in 2011. “My parents bought me a very lovely doll from Paris. It was very soft, it was supposed to be like flesh. I got hold of some scissors and cut off all of its fingers.”

Liorah Tchiprout also paints dolls that she has made, following puppetry training during her art degree. She was inspired by the dolls created for a Yiddish theater in New York, which were used for traditional tales and satire. “I thought they were really beautiful and expressive,” she said in an interview with Artnet News. Within her paintings, dolls conjure the emotions of everyday life. She recently showed at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery; in these paintings, the dolls occupy a fine line between personhood and objecthood, portraying human feelings with stilted physicality.

Paula Rego with her doll-like sculptures in the background. Photo courtesy of Victoria Miro, London.

“I think of the dolls as tools to make figurative art,” she said. “The intonation of a head or movement can become imbued with so much emotion. The dolls I make are very rudimentary, they’re almost like a grid to hang these emotions on.” Tchiprout enjoys the safety of working with dolls, as they are ultimately protected from painful experiences and carry less baggage than a living body.

“I do have a feeling of joy or playing when I’m working with them,” she said. “They’re dolls, they can’t be subjected to violence or sexual assault. Underneath their clothes is just wood and wire, they’re not real. They really crystallized a lot of things I was thinking about painting women. I come from a more traditional Jewish background; when I was at university, the Rabbi and his wife would come to shows. I wondered if I could I make contemporary painting that is interesting, that has something to say, but that is still tznuit, modest. Can you make work for multiple people to engage with on different levels?”

Renate Müller is a traditional toy maker and an artist, whose work is heavily rooted in scientific research. Since the early 1960s, she has been making therapeutic toys from leather and jute to help with balance training and orthopedic exercises for children. These toys make the challenging spaces of psychiatric and physio wards more palatable, bringing joy and comfort to mental and physical training. Many of her pieces are used within clinical settings, but her colorful elephants, hippos, and seals have become collectible artworks, leading to museum exhibitions and publications, highlighting their emotional power.

Jordan Wolfson, Colored sculpture (2016). Mixed media, overall dimensions vary with each installation. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London and David Zwirner, New York. Photo by Josh White

Animatronics are frequently used to chilling effect by artists, dynamically bringing toys to life. Precious Okoyomon marries the form of soft toys with technological invention. Their giant stuffed bear in the sun eats her children at Sant’ Andrea de Scaphis, Rome in 2023 was dressed in a diaper with a large white bow on its head. Surrounded by living plants and decaying brickwork, the bear would wake up at random intervals and let out an existential scream. This large toy, which is an ongoing icon for the artist, combined kitsch innocence with lost terror, surrounded by a world falling apart. There is something significant in this choice of a bear too—so terrifying and powerful in the natural world yet tamed and made cutesy in its frequent casting as a child’s toy.

Jordan Wolfson also works with animatronics, potently combining the magic of tales like Toy Story with the horror of possessed toys, characterized by the Chucky franchise. His Coloured Sculpture (2018) at Tate Modern bordered upon the unacceptable for some gallery-goers. It featured a larger-than-life boy puppet being thrown around upon its computer-automated chains. The boy would spin in the air before being hurled violently to the ground, often requiring replacement body parts. The puppet could be seen as an innocent victim, but it also had a chilling supernatural power, with glowing eyes and bared teeth. In keeping with Wolfson’s oeuvre, the artist enjoyed pushing visitors’ capacity for barbarity with this mutilated boy. “This is real violence,” he told the Guardian at the time. “It’s real abuse, not a simulation.”

Children’s toys are often created as miniature versions of people. They allow us to see ourselves mirrored and offer young people early interactions in which they can play out love, tenderness, and, in some cases, destructive violence. Their use in art, then, is always going to bring us back to what is resolutely human. Through these stand-ins, and our reactions to them, we are able to see our limits and psychology reflected back to us. At times, this can be too painfully haunting to look at.