Courtesy of

Anyone familiar with the story of modern art has probably heard of Tristan Tzara. Often described as one of Dada’s zany pioneers—along with Hugo Ball and Emmy Jennings, who had, in fact, already created the nonsense-endorsing movement’s signature platform, the Cabaret Voltaire, before meeting Tzara in Zurich around 1917—he has a place in the history books that is secure.

Max Ernst, Le Rossignol Chinois, Collection particulière.

Image: Courtesy of the City Museum of Strasbourg.

He has never, however, been treated as a singular subject of any interest, until now. The show, “Tristan Tzara, poet, art writer, collector: The Approximate Man,” which just opened at the City Museum of Strasbourg, is the first exhibition ever devoted to this complex character, a beating heart at the center of Europe’s creative and intellectual landscape in the first half of the 20th century. Curated by critic and scholar Serge Fauchereau with the collaboration of members of the Romanian government and the Bibliothéque litteraire Jacques Doucet, the 450-work show takes a serious look at the man behind the madcap performances and rambling manifestos.

Robert Delaunay, La Fenêtre (1912).

Image: Courtesy of the City Museum of Strasbourg.

Approximate, it turns out, is an apt way to characterize most widely held notions about Tzara, a Romanian in Paris. There is a second story to be told, and a third, and a fourth: that of Tzara né Samuel Rosenstock in 1896, to a Jewish family of means. That of young Tzara, the trilingual (he spoke Romanian, French, and German), a prolific writer, and an avid consumer of international literature from Christian Morgenstern to Stephane Mallarmé, who founded Simbolul magazine at the age of 16 with two schoolmates (one would later become the writer Ion Vinea, the other the painter and architect known as Marcel Janco). There is Tzara the essayist, playwright, literary critic, composer, film director, Tzara the collector of art négre (African art), and Tzara the Parisian gallerist. And there is Tzara the left-wing activist, who fought with the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, protested for Hungary’s liberalization and later denounced French actions in the Algerian War.

Jean Arp, La mise et papillons (1916/17).

Image: Courtesy of the City Museum of Strasbourg.

Ultimately, the show is short on Tzara’s own writings (these have been seen before, Faucherau maintains) and long on paintings, sculptures, photographs, and editions by a vast constellation of his friends and collaborators. The crew’s all here, of course, a stunning collection of little-known works in every medium by Man Ray, Constantin Brancusi, Pablo Picasso, Sonia Delaunay, Joan Miro, Marcel Duchamp, Hans Arp, Paul Klee, Marc Chagall, and Tzara had a hand in it all.

Joan Miró, detail of a lithograph, Parler seul poème Tristan Tzara (1950).

Image: Courtesy of the City Museum of Strasbourg.

“The Approximate Man” also features rare examples of the formative materials that inspired him—early editions of Le Chat Noir, paintings by Romanian Symbolists Arthur Segal and Corneliu Michailescu that evoke Fauvist landscapes by André Derain and Matisse’s portraits—many procured from small Romanian villages or lent to the show by family members. The blueprints for the flashy, avant-garde home Tzara designed with celebrated architect Adolf Loos in Montmartre are here, as well as photographs of his book-cluttered library and his collection of Mesopotamian art—not at all common for collectors of his time.

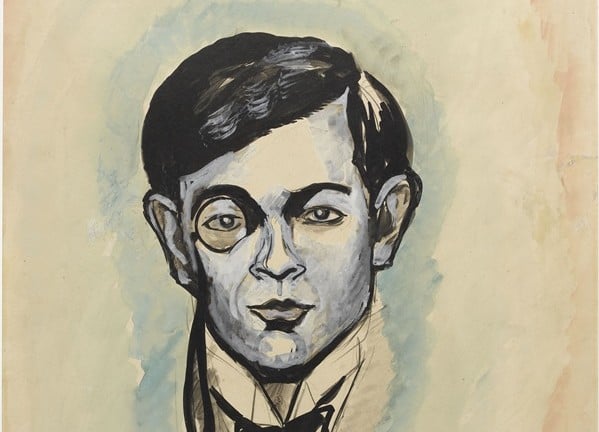

Marcel Janco, Portrait of Tristan Tzara (1919).

Image: Courtesy of the City Museum of Strasbourg.

“Tzara was a man of great charisma, with an enormous laugh, who did not take himself seriously,” Faucherau told press at the vernissage. “We wanted to create a broader Tzara, a more complex Tzara, who goes much deeper than the wacky, nonchalant character many imagine him to be. He will never be a popular auteur, that’s for sure—but I think this show will make him more comprehensible.”