Television painting icon Bob Ross famously said, “It’s the imperfections that make something beautiful.” In “Ugly Pretty,” leading artists, art professionals, and creatives delve into the idea of imperfect beauty by analyzing a single artwork. Through their perspectives, we uncover how these unique works reshape the way we view the world. Listen as they describe the artwork in their own words.

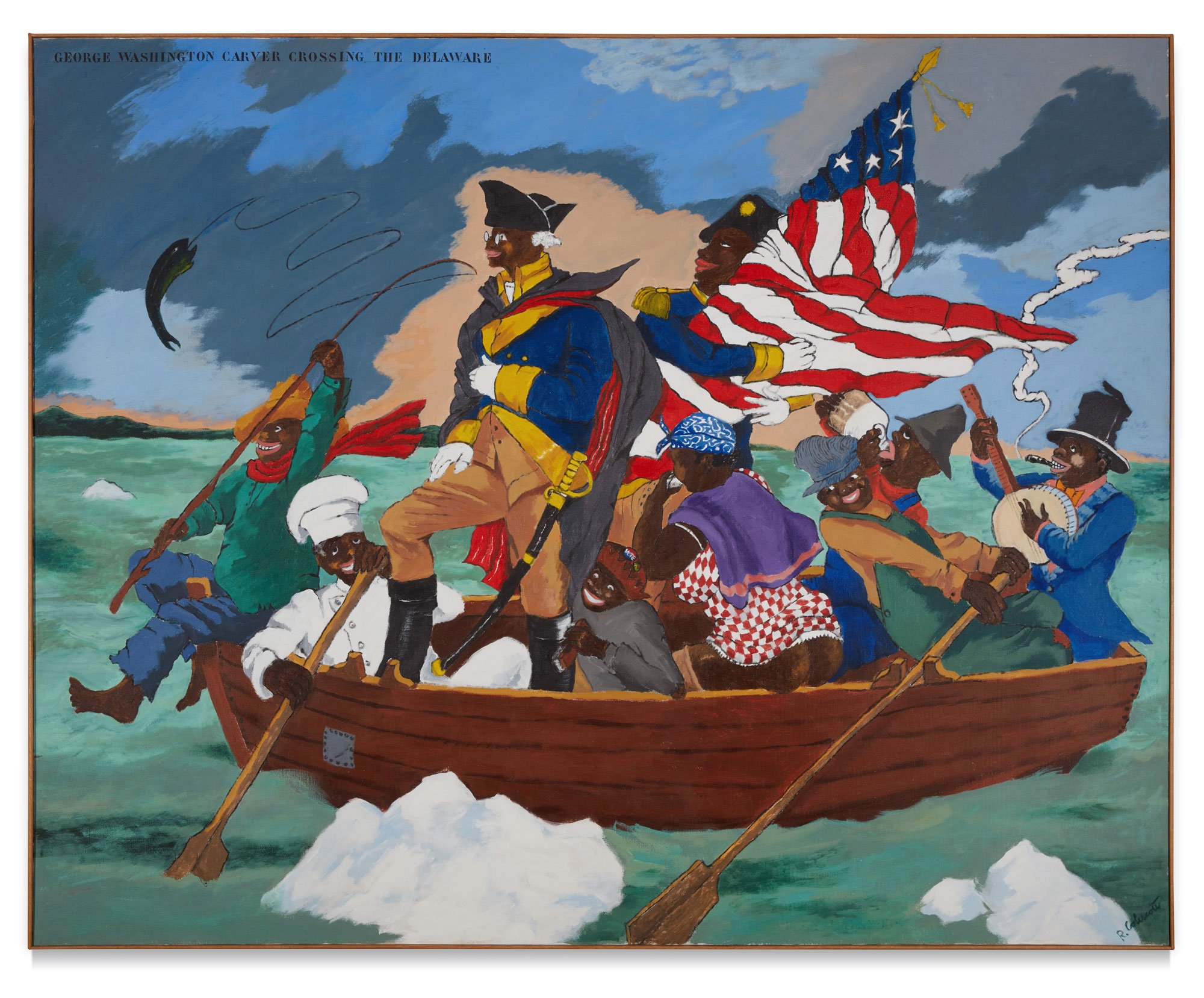

I think Robert Colescott’s George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware embodies an idea of imperfect beauty. The work is inspired by and serves as a commentary on George Washington Crossing the Delaware, the iconic painting by Emanuel Leutze from 1851. That painting depicts George Washington crossing the Delaware River, heading toward the Jersey shore in a moment that symbolizes the founding of America during the Revolutionary War.

In Colescott’s piece, George Washington Carver, one of the most prominent black scientists of the early 20th century, takes the place of George Washington. The boat is surrounded by icebergs, but what’s striking is the replacement of the historical figures in Leutze’s painting with caricatures and stereotypes. Instead, it’s Aunt Jemima, it’s Uncle Ben. It’s all of these Black stereotype figures that have been resident in the minds of the American public through mass produced images. So this is an ugly pretty painting to me for so many reasons, because it represents the ugly underbelly of the U.S. and how these images have shaped who we are and how we see the world. It’s pretty, because I think it actually does that really important work of opening up uncomfortable conversations that allow people to make a better world to live in.

I first encountered George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware in The Black Male exhibition curated by Thelma Golden. Later, as a curatorial fellow at the Whitney, I included it in a show I co-curated called As Time Goes By. That was in the ’90s. My initial reaction was, “Wow, seriously? This is in a museum?” The discomfort it evoked felt both historical and contemporary. It’s a very painterly work—the brushstrokes, the vibrant colors—it feels freshly painted. You can sense Colescott’s hand in it. But the themes it addresses—anger, a call to action, and a sense of promise—are what really stuck with me. It’s exhilarating to think art can labor on behalf of world issues and personal struggles.

Robert Colescott, Miss Liberty (1980). Courtesy of Bonhams.

Colescott’s practice centered on the Black figure, addressing not just representation but the social realities of the time. His work recontextualizes mass-produced images, like Aunt Jemima, which carried subliminal messages of domesticity and inferiority. Yet, these figures also have revolutionary histories. There’s so much discourse layered into his work—it’s a history painting and one of the greatest American works, challenging us to question comfort and propaganda.

If imagery can shape us negatively, it surely has the potential to do the opposite—to inspire positive change. I believe art can change the world because it changes people, and people change the world. I think that museums are more than repositories of artifacts or arbiters of taste. They exist in the spaces between the comfortable and the uncomfortable, the positive and the negative, the imagined and the real. I believe museums can serve as safer spaces for uncomfortable conversations—not necessarily “safe spaces” in the absolute sense, but spaces where people feel encouraged to discuss tough issues and consider ways to enact change.

As told to Margaret Carrigan at Art For Tomorrow in Venice (June 5–7, 2024), where Artnet was an official content partner. Audio production provided by executive producer Sonia Manalili.

Sandra Jackson-Dumont is the director and CEO of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art since 2020, which opens to the public in 2026. She previously held roles at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Seattle Art Museum.