Robert Longo’s drawing of Cindy Sherman

The big ‘80s show that just opened at the Modern in Fort Worth—“Urban Theater: New York Art in the 1980s”— is good, to my relief. It is, as expected, big and graphic and punchy. The iconic work is here; it’s what turns on curator Michael Auping, who really belongs to this era, and his rekindled fondness for certain aspects of the decade transfers to the viewer. If you walk into the show with trepidation, you’ll probably walk out feeling at least a little better about this uneven and unsettling moment in recent art history. I would have loved for it to have been even bigger; it could have easily engulfed the whole museum and then some, but then Auping would have been dealing with a lot more of the patchiness of ‘80s art. Here, limited by space, it comes off as cohesive.

I don’t know if this concentration of the “good” stuff helps or hurts the show’s overall energy level; it may be more formal than I’d like. But, as I told a colleague right after I saw the show, I may not be the most objective judge of an ‘80s show, because like a duckling, this era is my primary imprint. It was when I first started really looking at contemporary art. Cindy Sherman was my first memorable museum outing as a teenager (at the DMA). In high school, I wore my limited edition Haring Swatch until it broke. And in college we were all obsessed with David Salle and Eric Fischl and Nan Goldin. Etcetera.

By art history standards, the ‘80s legacy is unsettled still, though not for much longer. While hipster Millenials have been joyfully and not ironically borrowing style cues from that decade since even before Vice Magazine arrived in NYC in 1999, those of us who came of age in the ‘80s or lived through it as adults have had a complicated and sometimes dread-inducing association with that time.

Keith Haring

A lot of what’s problematic about the ‘80s—deregulation and Reagonomics, the unchecked hunger of a new art economy, the beginning of the narcissistic marketing of oneself, the AIDS crisis that killed so many bright stars and created a seemingly endless creative vacuum—still resonates today. Lee Atwater’s evil master plan for co-opting the religious right and rural vote for the GOP happened then; we see where that got us. And the kind of ugly, post-modern free-for-all in design and clothing and music and architecture got going in the ‘80s. Things started to feel plasticky and superficial and unrigorous around that time. Pop music production was (despite an almost worldwide ongoing love affair with hits of early MTV) terrible—super synthetic and flattened. There are several generations of adults who just don’t want to revisit all that, and they certainly don’t like to look at photos of themselves taken in 1985. Yeesh.

So some would like to dismiss the whole decade, including much of the art. At the same time, right now the ravenous and excavating appetite of collectors and connoisseurs keeps looking backward, and the art of the 1980s is up for reexamination in a big way. Longo’s “Men in the Cities” felt dated six years ago, but I’ve started to see a lot of ‘80s Longo and Kruger imagery being used illustratively in current pop culture. There’s a sensibility there that’s starting to feel fresh again. Of course. Thank Supreme, I guess. Follow the trickle up. Or just accept that the internet has made every well-documented decade accessible to all of us all the time, and anything earlier than 2001 is up for the nostalgia treatment.

Jean-Michel Basquiat

But pre-internet, a lot of the artists in the ‘80s, especially those in New York, were dealing with their own here-and-now in a reflexive and boisterous way, and, again, the best thing any exhibition could communicate is that energy. And I do think the Modern show, almost by default, captures a bit of it. Street art came into its own at that time, of course, and the big, braggadocious gestures of Schnabel and Mary Boone’s macho stable were everywhere too. These big Haring tarps and some of Basquiat’s work and Schnabel’s broken plate paintings are at the Modern, and one of the best things in the show is an environment made by Kenny Scharf (I was surprised, because though Scharf was always a downtown super-connector, his art is generally unconvincing) —you can walk into his dayglo cave-like time-machine and it reignites some of the nightclubby, counterintuitive optimism of the time. One should keep in mind that the changes between the early ‘80s and the late ‘80s meant the difference between downtown post-punk DIY-ness of Fab 5 Freddy—he and his cohort were still reeling from and riffing on recession—and the ultra-slick cocaine-fueled narcissism of Koons and “American Psycho,” which is a breathtaking range of aesthetics and concerns. You can’t pin the whole of the ‘80s on Holzer’s earliest Inflammatory Essays (circa 1980) any more than you can on Mapplethorpe’s photos of gimps (1985), or Christopher Wool’s resilient text paintings (1990). It all unfolded in due time on one tiny island.

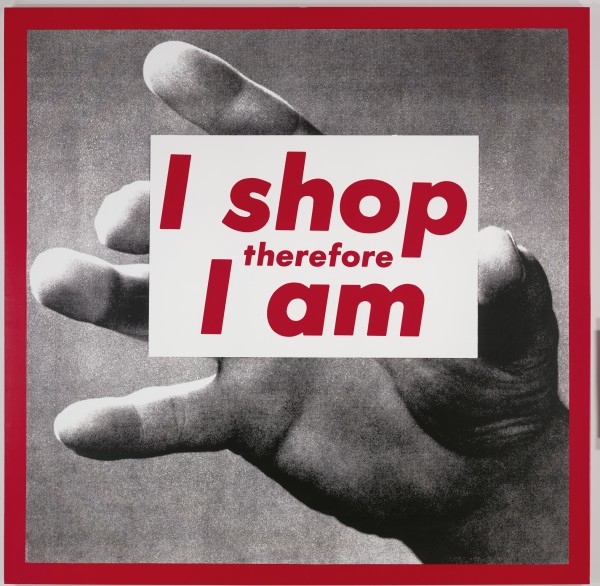

Barbara Kruger

Auping secured some things I was happy to see. A whole room of Goldin’s aesthetically un-aestheticized photos of her and her scruffy friends burning themselves out; a wall dedicated to Colab’s seminal “Times Square Show”; three of Longo’s best jerking Men (including one woman, who just happens to be Cindy Sherman, his better half at the time); another room given over to the Guerrilla Girls via documentation and still-charged ephemera. Ross Bleckner’s heartbreaking “Sanctuary”—one of the best paintings of the era, is here. Laurie Anderson bangs away on her own body in a big video installation of a segment from “Home of the Brave.” (I do wish there was more video in this show.) And ’80s graphics still look sophisticated, and well-suited to delivering messages. Fifteen years ago I sort of agreed with Robert Hughes in dismissing Kruger’s designer-y soundbites, but now she seems so prescient and wise, because we’re still dealing with the dirty politics and distressing takeover of consumer culture and war on women she was addressing back then. The Clinton years and Generation X may have offered a moment of relief, but now these issues and the way money and power flows is worse than ever.

Kenny Sharf

The clear takeaway is that these artists were fearless. They called it like they saw it. Politics didn’t scare them, and they knew how to use media because they were the first generation to grow up inundated by it. They called out the powerful, and often gained their own power in the process. And the tandem rise of the art dealer and art collector is telling. Economically, the decade was dizzying.

Oh, New York! For a lot of fans of the city, the ’80s were the last years of it being fertile and open-ended, and also the first time the city hinted at what it might become. The movie “Smithereens,” directed by Susan Seidelman, was shot in 1982, and downtown looks like an unrecognizable, post-apocalyptic (but very interesting) shit hole. The ‘80s windows in Warhol’s diaries and Interview Magazine are a great resource for watching the decade unfold in real time, downtown and up, and while I flip through these at home for the millionth time, I’m also starting to think: But what about the 1990s? For they, too, are upon us. So go see this show before we move on.

Urban Theater: New York Art in the 1980s at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Sept. 21-Jan. 4, 2015.

This post originally appeared on Glasstire on Friday, September 19, 2014.