In the summer of 1879, Vincent van Gogh was living in the Borinage, a poor coal mining region of Belgium, working as a priest. He sat down to write a letter of gratitude to his brother, Theo, who had recently come for a visit.

“Like everyone else,” he wrote. “I have need of relationships of friendship or affection or trusting companionship, and am not like a street pump or lamp-post, whether of stone or iron, so that I can’t do without them without perceiving an emptiness and feeling their lack, like any other generally civilized and highly respectable man.”

Through such feelings of connection to others, Van Gogh wrote, “one is aware that one has a reason for being, that one might not be entirely worthless and superfluous but perhaps good for one thing or another.”

Helewise Berger, curator of the exhibition “Van Gogh’s Inner Circle: Friends, Family, Models” at the Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch, which opens tomorrow and runs until January 12, 2020, said that it was time for a museum to “do justice to the broad group of people around Van Gogh.” The show sets out to explore how his network of family and friends supported him—emotionally, fiscally, and socially.

Speaking at a press conference on Thursday, Berger said the museum is trying to refresh the longstanding image of the Dutch artist: “We aim to put an end to the image of Van Gogh as a lonely, tormented artist, who was never appreciated in his own days.”

Woman (‘Sien’) seated near the stove by Vincent van Gogh, (1882). Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

Van Gogh, the Myth

Through nearly 100 objects, including 16 original Van Gogh paintings and 17 of his works on paper, as well as personal letters and paintings by his friends, the show presents an intimate view of his friendships with fellow artists such as Émile Bernard, Paul Signac, and Anthon van Rappard, who was his boss at Goupil & Cie art gallery’s branch in The Hague. The perspectives of his pupils, who described him as strict but playful, are also included, along with the voices of several important women in his life.

“The image of the artist as doomed, and a lone wolf who went unappreciated through life is simply not true,” said Sjraar van Heugten, the exhibition’s guest curator, and a leading authority on Van Gogh. Although scholars have long known that Van Gogh was very well connected in artistic circles and that he had close ties to his family, the outcast image has persisted in the public, said van Huegten. Popular films, from Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 “Lust for Life” to Julian Schnabel’s 2018 “At Eternity’s Gate,” have sustained this myth.

The curator said the idea of this exhibition was catalyzed by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s biography, Van Gogh: The Life from 1994. That work became the definitive guide to the artist for the ensuing decades, despite the fact that Van Heugten felt it cast the artist as “a complete maniac.”

“He was a difficult man,” Van Heugten concedes. “He was not very huggable; he was not a teddy bear. But he was also someone who was very much appreciated by people in his life, and that was very important to him.”

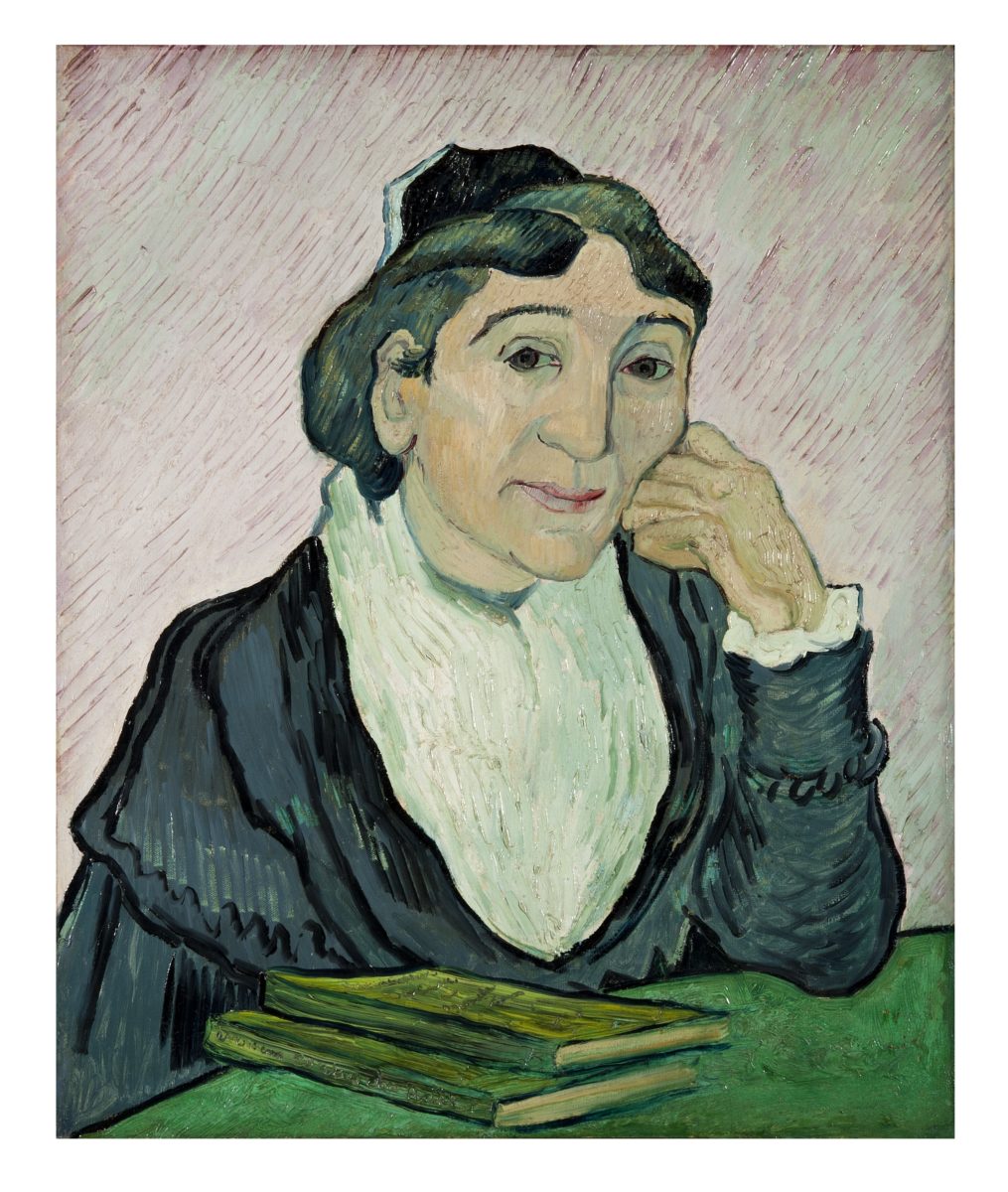

Madame Roulin Rocking the Cradle (La berceuse) by Vincent van Gogh, (1889). The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection.

The Inner Circle

Van Gogh was the son of a vicar. His family was religious and socially prominent. “They had to be role models in the village where they lived, so [they were] strict, yes, but warm and empathetic as well,” said Van Heugten. “In the Netherlands, we would call it a ‘warm nest.’”

At the museum, a full wall is devoted to very personal drawings Van Gogh made of Sien Hoornik, a woman he met in The Hague in 1882. He had described her to his brother, Theo, in a letter as having been “abandoned by the man whose child she was carrying.”

“I took that woman as a model and worked with her the whole winter,” he wrote. “I couldn’t give her a model’s full daily wage, but all the same, I paid her rent and have until now been able, thank God, to preserve her and her child from hunger and cold by sharing my own bread with her. When I met this woman, she caught my eye because she looked ill. I made her take baths and as much fortifying remedies as I could afford, [and] she’s become much healthier.”

Sien became Van Gogh’s girlfriend. She posed naked and visibly pregnant for his lithograph, Sorrow. After she gave birth to her daughter, the artist moved in with her, and they lived together in The Hague for a year.

Portrait of Marcelle Roulin by Vincent van Gogh, (1888). Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

“He was so happy when he lived with Sien and he had a little baby who was crawling through the studio,” said van Heugten. “Domestic life—he loved it. It was the only time he did have a family, and it was only for a year, but he was happy.”

Van Gogh’s fraught friendship with the artist Paul Gauguin figures only briefly into the exhibit, which instead gives more attention to his relationship with the Roulin family in Arles, with whom he developed a close bond. He made 25 paintings and drawings of members of the family, including the youngest baby, Marcelle, just after he was born. “Van Gogh loved children and especially babies,” said Van Heugten. Another painting depicts Madame Augustine Roulin with her hands holding a rope to rock Marcelle’s cradle beyond the frame.

Getting a better grip on these relationships, said Van Heugten, can help us understand that the narrative of the solitary genius artist is just “a romantic notion.” Great artists almost always come out of a rich social context.

“If he had been the solitary artist that people liked to imagine, he never would have developed into the person he was,” said Van Heugten. “His whole development depends on that.”

“Van Gogh’s Inner Circle. Friends, Family, Models” opens on September 21, 2019 at the Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch, Netherlands. It will be on view until January 12, 2020.