Discussions about young artists on the rise frequently employ the passive voice. He “was chosen” for a competitive residency or solo exhibition; she “was accepted” to an elite art school. But the trajectory of newly minted art star Vaughn Spann, who recently opened a sold-out solo show at Almine Rech gallery in New York, is no accident. Instead, it is the result of a series of deliberate and canny choices on the part of the 27-year-old artist.

Less than two years after graduating with an MFA from the elite Yale School of Art, Spann’s career has gone into overdrive. His work—which alternates between lush portraiture and mixed-material abstractions—has already been included in more than three dozen group shows across the US, including a prominent position in the inaugural display at the newly opened Rubell Museum in Miami.

His latest exhibition—sold out within a week of the opening—presents a dozen paintings with an average price of $50,000 (In general, prices for his work range from $20,000 to $90,000 depending on size). Two years ago, similar works were selling on average for under $20,000. Spann’s work has already been collected by the likes of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, and corporate collections such as the UBS Art and the Credit Suisse Corporate Collection.

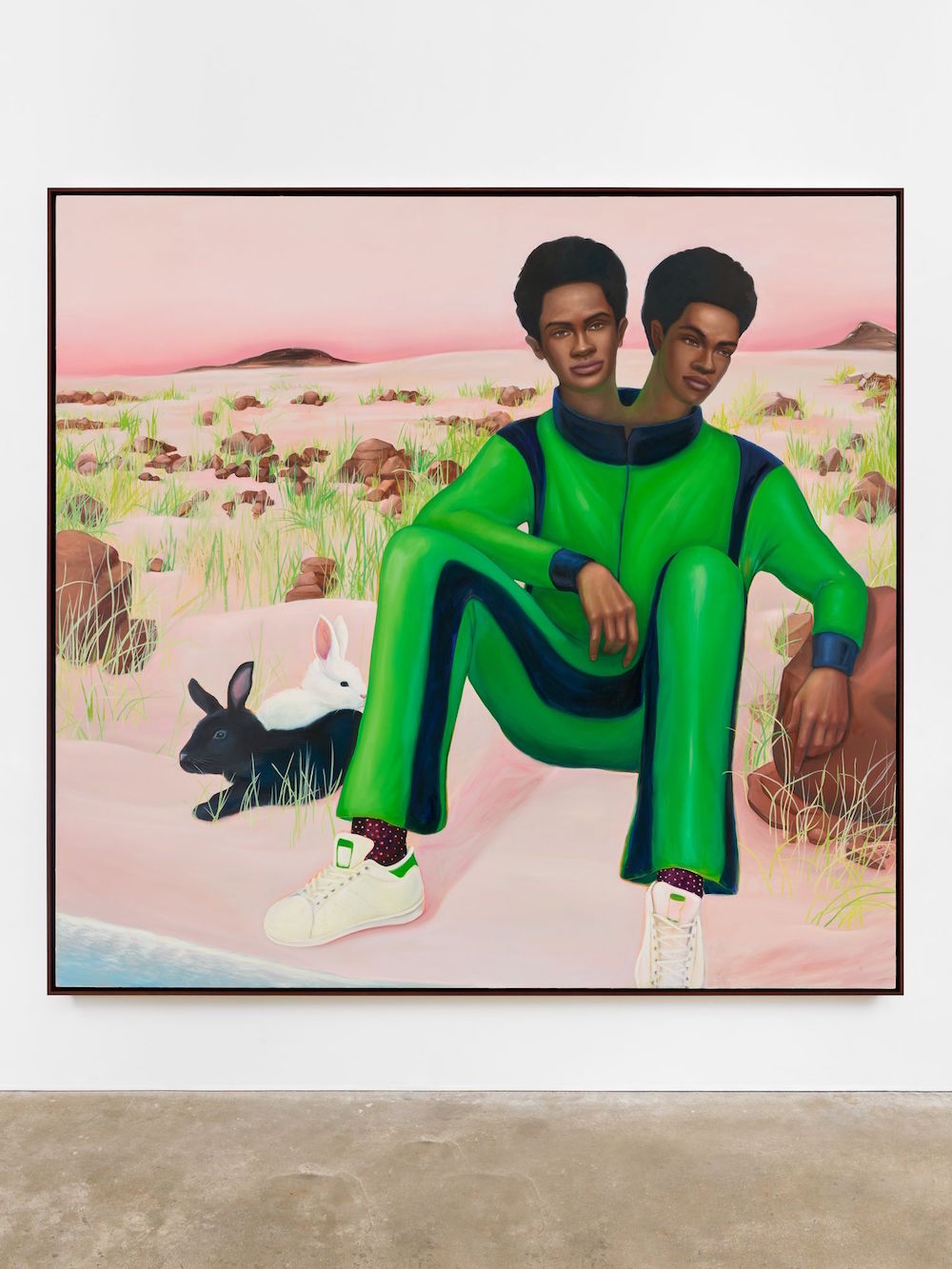

Vaughn Spann, Cosmic Symbiote (Marked Man) (2019). Photo by Dan Bradica. Image courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech, New York.

Growing up in Orange, New Jersey, Spann says he “didn’t have a lot of [exposure to] art per se, though I definitely saw a lot of murals and local art around the town.” That was enough to give him the bug, and he found himself constantly drawing, whether it was “portraits of people, sketches, landscapes—I always had a free-running imagination regarding art.”

Nevertheless, just as governing and running for election require different skill sets, making art and navigating the art world are two different beasts. “When it came down to being an artist, I didn’t know what that entailed in a serious manner,” he tells Artnet News. “I only knew what that entailed in a very lighthearted, naive manner.”

Hitting the Ground Running

That naïveté didn’t last long, however. Spann was forced to confront the reality of the commercial art world as a student at Yale, where, unlike almost any other art school in the country (or, in fact, the world), collectors and art dealers are constantly circling to find new talent, particularly at a moment when the art world is paying more attention to the work of black artists than it has in the past.

“During grad school, you should be focusing on the potential framework of your work or the art historical context,” Spann says. “But we’re attending a school that has a lot of visibility, so we can’t deny that. We can’t just sit under a rock. I feel like there has to be a balance, where maybe there can be a course to talk about some preparedness. People do come to the school or send emails” looking to see artists’ studios, he says.

In the absence of formal instruction on how to navigate the nuts and bolts of shaping a career, Spann constructed his own curriculum with the help of other artists familiar with the spotlight.

It was artist Rashid Johnson, for example, who first brought Spann to the attention of the mega-collectors Don and Mera Rubell, while fellow Yale alumnus Titus Kaphar was, in Spann’s words, “the ultimate mentor.” Kaphar used part of his MacArthur “genius” grant to create a year-long residency program called “NXTHVN” (pronounced Next Haven) which Spann just completed. Such spaces can offer a space of creative nurturing for students, especially black students, who have navigated the pressure-cooker of an elite art school. The support of dedicated collectors, principally early supporter Bernard Lumpkin, was also key, Spann says.

Vaughn Spann, Beachside (2019). Photo by Dan Bradica. Image courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech, New York.

“Yale could be a little bit of a polarizing program at first,” the artist says. “To be clear, there are very different practices and art-making going on. You gravitate toward the faculty that you need to gravitate to. You have instances where your conversation can be very productive versus not productive at all. It’s honestly what you make of it.”

Both Johnson and Kaphar were critical in helping him avoid some “rookie” mistakes, Spann says. “I have people looking out for me to tell me things, like I should know where my work is being placed and other things an emerging artist might overlook,” he says. “Rashid and Titus have helped me sharpen up.”

A Fluid Approach

Spann has also avoided a pitfall that lots of artists with early success can fall into: the temptation to settle on one narrow, signature style. The artist, who had initial exposure via group shows at New York galleries Kravets Wehby and Fredericks & Freiser, has remained committed to making both surreal figurative scenes and abstractions, as well as works that float between the two spheres.

The Almine Rech show, “The Heat Lets Us Know We’re Alive” (January 15–February 22), includes 12 new paintings that range from near-allegorical compositions depicting two-headed figures and animals in brilliantly hued clothing alongside giant recurring X’s and American flags.

Vaughn Spann, Untitled (Flag) (2019). Photo by Matt Kroening. Image courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech, New York.

The work is “quite original, new, and fresh,” dealer Almine Rech tells Artnet News. “He has many directions. That interested me a lot. There are many open doors.” Rech first encountered Spann’s work when the gallery included him in an October 2018 group show in London. “We wanted something figurative and very contemporary,” she says.

Conversations and a studio visit with the artist in Newark, New Jersey followed. When Rech asked Spann about the significance of the X in many of his paintings, she says, he told her it was a reference to his own personal experience with stop-and-frisk measures by police over the years. “It’s not abstract, the X,” she says. “In fact, it’s him.”

Rech, who represents the artist in Europe and the UK, also noted keen interest for the work in Asia (she operates in Shanghai), where the graphic and easily recognizable X and flag symbols have resonated with audiences.

The Importance of Balance

Spann stressed the importance of balance when it comes to everything from studying at Yale while raising two young children to vetting collectors and deciding which galleries to show with.

“My whole M.O. is that it’s always family first,” says Spann, who has an eight-month-old and three-year-old daughter. “When I started [at Yale], my daughter was a tot, so some days she would be in the studio coloring as I try to get my work done and my wife was in the area living near the studio. That balance was critical.”

Vaughn Spann, Sweet Red (2019). Photo by Matt Kroening. Image courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech, New York.

This kind of equanimity has likely helped Spann make canny choices, but it will be equally imperative for other artists coming up after him. Spann says the practice of dealers and collectors trying to court students at Yale seems to have only intensified since he graduated. His advice? “It’s like a dance. You allow certain people to come into your life, and to help you. At the same time, you should also vet, and not allow that space to become one where people are intruding on your time and studies.”

Spann says he often hears from stressed-out students seeking guidance about which galleries to sign with. He tells them to stay humble and take the long view.

“It’s so funny, because the same galleries come to these programs over and over. I’m like, ‘To be honest, you shouldn’t even feel special. Don’t even worry about this stuff. The best that you can do for yourself is to wait on any of this… take a show or get into a summer group show, whatever it is. Be patient—because the vultures, as they say, are out there.'”