Inside the palace of the high priest of Vodoun in Benin, there is a framed portrait of George Floyd, with Breanna Taylor and Rashad Lewis on either side. Below their images is a line written in red letters: “Remember your ancestors.”

The Nigerian curator Azu Nwagbogu saw this on a research tour through the country that he took after he was tasked with the honor of curating the first pavilion for Benin at the Venice Biennale. Back in December 2022, he had received an unexpected phone call from the Beninese President asking him to stage the first pavilion for the West African nation. Nwagbogu then went on a journey across the country to meet with traditional rulers and custodians of culture to discuss Beninese history, culture, art, and the impact of the transatlantic slave trade.

The title of the pavilion “Everything Precious is Fragile” was inspired by Nwagbogu’s meetings with these rulers, and the Yoruba concept of Gèlèdè that focuses on the feminist idea of “rematriation” or advocating giving and receiving. The pavilion, entirely funded by the government of Benin, is among a total of 13 African countries that are presenting official national pavilions—up from nine in 2022.

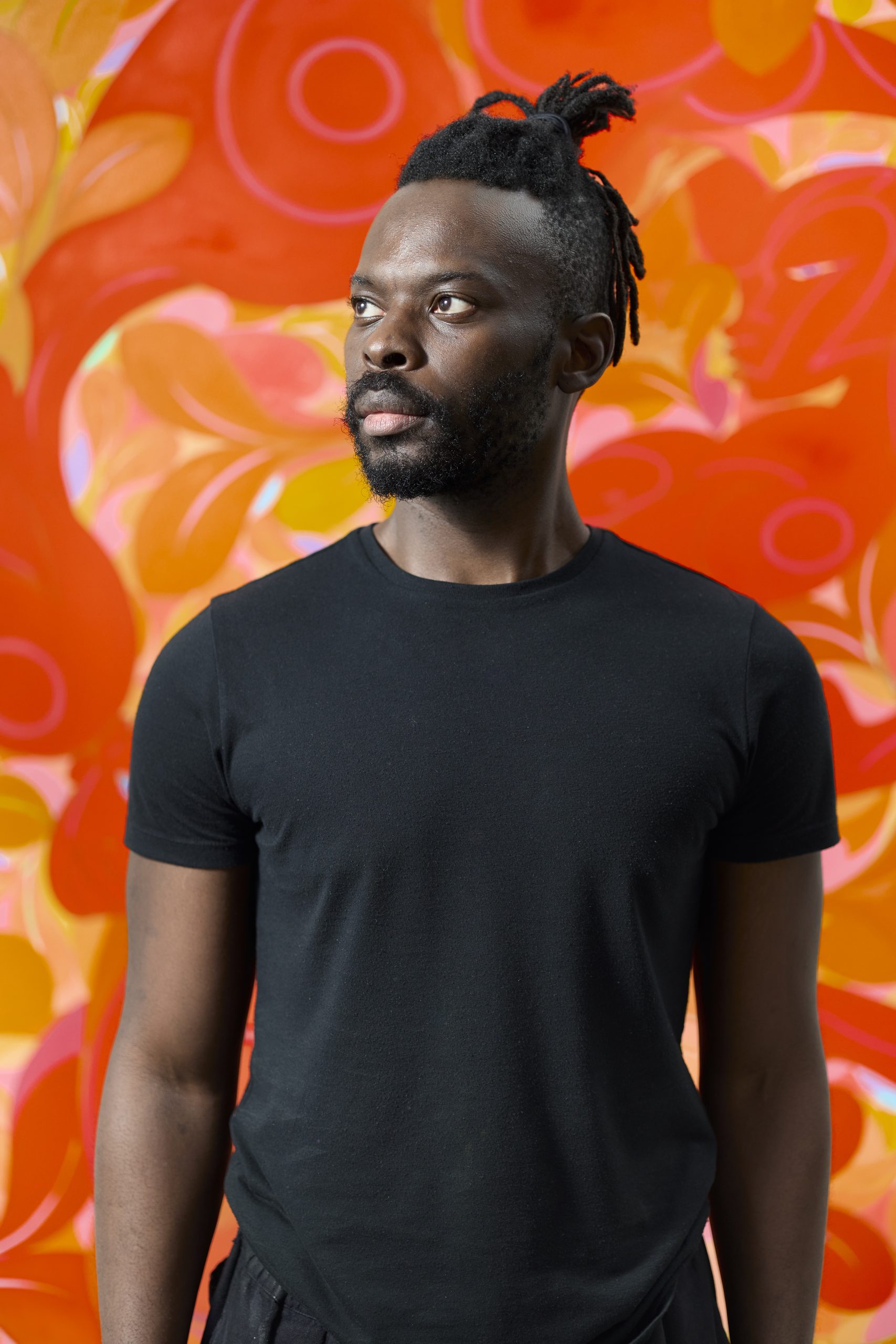

Benin: Curator Azu Nwagbogu on his trip around Benin. Credit: Ugochukwu Emeberiodo

Among the 13 are three additional debutants staging their first ever national pavilions. These are Senegal, which will present “Bokk – Bounds” by Senegalese Alioune Diagne in the Arsenale, staged with Galerie Templon. Ethiopia is presenting “Prejudice and Belonging,” featuring the work of Tesfaye Urgessa, and Tanzania is displaying the group show “A Flight in Reverse Mirrors.” Returning African nations include Egypt, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ivory Coast, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

“We are not interested in treating Venice like some kind of Mecca where we go every two years and that’s it,” Nwagbogu noted. “Europe is not our center. Europe is an important place to have a conversation, but it is not the center of the world. After Venice, we need to bring the focus and intellectual capital back to Africa to have important conversations.”

The 13 pavilions are not alone—there are another 18 national pavilions from Europe and North America that are presenting artists from Africa or the diaspora. These include the Dutch Pavilion, which is showing the work of Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise, a collective of Congolese artists. Kapwani Kiwanga, a Canadian artist of Tanzanian descent, is presenting new work for Canada. French-Caribbean artist Julien Creuzet is representing France, co-curated by Cindy Sissokho and Céline Kopp; Portuguese-Angolan artist Mónica de Miranda is showing work alongside others in the Portuguese national pavilion, and British filmmaker John Akomfrah, of Ghanaian descent, is representing Great Britain.

John Akomfrah at his London studio, 2016. Photo: © Jack Hems, courtesy of the British Council.

Artists from the continent can also be found in Pedrosa’s main exhibition “Foreigners Everywhere”—where 54 artists from the 331 artists and collectives are African. Participants include Kudzanai Chiurai from Zimbabwe, known for his mixed media work that comprises paintings, videos, drawings, and photographs to tackle socio-political issues in his home country; Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi, who is 93 years old, will also be on view. He is known for his paintings and drawings that combine motifs from African, Islamic, and Western art.

“Venice is like an old lady that needs to be redressed,” Cameroonian-French curator Simon Njami said in a telephone interview from Venice. He has curated “The Blue Note” for the Ivory Coast Pavilion, which features five Ivorian artists inspired by the blue note in jazz music, which has its origins in the music made by African slaves. “I think that more African countries are understanding the importance of soft power. The Venice Biennale is still a platform where people can show their skills and talk for themselves. I think there’s a growing consciousness of the importance in showing art. Africa has a certain image and art can give another image.”

Work of Alioune Diagne, who is representing Senegal at the Venice Biennale. Photo © Laurent Edeline. © Courtesy of the artist and TEMPLON, Paris, Brussels, New York

“[‘The Blue Note’] is about resilience,” Njami said. “It’s a double-sided lesson for Africans and all people complaining that they’re victims due to colonialization. The lesson is that people with nothing to their names and no land invented the blue note that made a revolution in music because it created blues jazz. You don’t need to be rich to be able to say something.”

Njami, who previously called Africa’s participation in Venice a mess, believes that this year more African governments are supporting their country’s artists through representation that allows them to display their art on their own terms and not through the eyes of foreign curators. He said that more African nations will likely be represented in Venice in the future as further governments realize the social and political value of showing their art internationally.

But they do not always return. Ghana, which made an impressive debut in 2019 and participated again in 2022, is not presenting a pavilion this year. A Ghanaian art dealer said over telephone that this was due to a lack of funding.

Artists themselves are often key lobbyists helping to push for the launch of national pavilions and for their continuation year after year. “Since I was an art student, I always wondered why Ethiopia wasn’t represented in Venice,” the Ethiopian artist Tesfaye Urgessa, who is representing the country for their first pavilion, said in an interview.

Tesfaye Urgessa is representing Ethiopia at the Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Tesfaye Urgessa and Saatchi Yates. Photography by Kameron Cooper.

Urgessa’s alluring abstract figurative paintings, which are determined and unapologetic, reflect his experiences of racism after moving from Ethiopia to Germany. One year ago, he requested support from the Ministry of Tourism. After a lengthy conversation and much convincing, the ministry’s officials agreed. Yet funding for the Ethiopian pavilion did not come from the state, but was raised from private donors.

Nigeria, which staged its first pavilion in 2019, is another example of a mix of state blessing coupled with private funding (other pavilions in the Giardini, like the U.K., have mixed sponsorship). Titled “Nigeria Imaginary,” it will feature works by Ndidi Dike and Yinka Shonibare in a group show. Its main sponsorship comes from Qatar Museums. “There’s a real sense of optimism and dreaming that sits within the Nigerian psyche,” Aindrea Emelife, an art historian and curator of modern and contemporary art at MOWAA (the Museum of West African Art which is due to open this fall) and the curator of the pavilion, said in an interview.

“Nigerians often say, ‘no condition is permanent,’” noted the curator, who is based between between Lagos and London. “It’s such an interesting phrase because it acknowledges that things currently are not great, but it still reflects the opportunity that things could be better.” She emphasized how the theme of the pavilion looks back at specific moments in Nigerian history and personal memory. It also “explores roads not taken and a new imagination for the nation,” she added.

Aindrea Emelife is curating the Nigerian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Courtesy Aindrea Emelife

While African art is more present than ever, questions over misrepresentation linger. The Cameroonian pavilion is once again jointly curated by Cameroonian Paul Emmanuel Loga Mahop and Sandro Orlandi Stagl from Italy. Stagl was one of two foreign curators responsible for Kenya’s controversial showing in 2015, which the African nation then disowned. This year, the group exhibition is called “Nemo propheta in patria” (translated: no man is a prophet in his own land) and includes Jean Michel Dissake and Hako Hankson.

Crucially, increased African representation at the Venice Biennale means greater visibility and dialogue on the African continent as well. It also offers a chance to change the narrative. “Whether we show our works here in Venice or in a museum, wherever it may be in the West is great,” Ced’art Tamasala and Matthieu Kasiama of CATPC said as they finished installing in Venice. “But it means nothing unless we can share the benefits with our entire community, and we can create a level playing field in which we can all have access to the events that, so far, we have been excluded from.”