For many, the Palace of Versailles and its spectacular gardens designed by André Le Nôtre still represent an idea of architectural excellence, an acme of taste, grandeur, and elegance à la française. Since 2008, it has also become a site of experimentation on the way contemporary art can be shown in dialogue with historical settings.

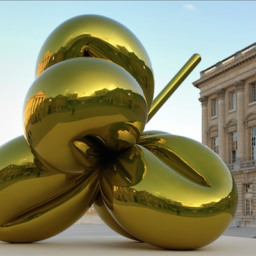

The program in its current form started under former president Jean-Jacques Aillagon’s tenure, with a spectacular─and controversial─Jeff Koons exhibition. Xavier Veilhan, Takashi Murakami, and Joana Vasconcelos soon followed. And next summer, Anish Kapoor will do the honors (see Anish Kapoor Tapped for 2015 Solo Show at Versailles).

Catherine Pégard, a former political journalist and advisor to Ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy, was appointed at the helm of the prestigious institution in 2011. Four years into the job and ahead of her presentation at “VIEW: A Festival of Art History,” at London’s French Institute this weekend, she caught up with artnet News.

How did you approach the contemporary art program you inherited from your predecessor, Jean-Jacques Aillagon?

First, I thought it was completely right to show contemporary art at Versailles, as I believe art creation feeds on the past. I thus continued what had been started. Jean-Jacques Aillagon had invited Joana Vasconcelos, and she came in the summer of 2012. I then tried to deepen the dialogue that had been initiated between Versailles’s heritage and contemporary art, between past and present. In 2013, for the 400th anniversary of André Le Nôtre’s birth, I invited Giuseppe Penone. Our collaboration with this artist, who has worked a lot with trees—including with a tree fallen during the storm that wrecked Versailles’s park in the winter of 1999-2000—was a perfect example of the kind of exchange I wanted to foster here.

With Lee Ufan, whose work isn’t inspired by European culture, it was even more fascinating to see how he dealt with Le Nôtre’s gardens (see Lee Ufan Exhibition Storms Versailles). For him, the ultimate outcome of Le Nôtre’s perspectives was an absence, a void, and he worked with that narrative. This year, we’ve invited Anish Kapoor and, with him, we’ll go back to contemplating history. Although he hasn’t finalized his project yet, we already know that he has taken more of a political stance on Versailles as a place, rather than started a dialogue with those who built it.

Could you tell us more about the way he approached it?

It’s going to be a new reading of Versailles. Unlike his predecessors, Kapoor will show only five or six pieces. Each artist identifies the places they want to work in, with all the challenges that this might entail. Sometime, we have to discourage them from presenting their work in a particular spot for technical reasons. We can’t install contemporary artworks in spaces that would be too fragile, or too historical, or too archeological. The technical difficulties of setting up a contemporary art show in Versailles’ gardens─and even more so, inside the palace─are tremendous. Then it comes down to a conversation between the artist, us, and the curator, Alfred Pacquement, whom I asked to accompany the artists invited to show at Versailles.

What particular political events caught Kapoor’s imagination?

He’s more interested in a confrontation with the place, and its dramatic and most spectacular moments. For instance, I know he’s particularly interested in the French Revolution, as well as in Hubert Robert’s ruins paintings … things that have to do with deconstruction, instability, and the difficulty of maintaining a place. It’s really interesting to see that this is what appealed to him at Versailles, which also represents an idea of permanence.

During your talk in London, you’ll speak about the spirit of Versailles. How does one keep it alive?

It has to be a constant preoccupation: one cannot think of Versailles other than as part of its time, of its century. Today, our duty is to think about how to open it up to the world—as you know, 86 percent of our visitors come from abroad—and how to anchor it within its time.

Most major historical institutions across the world now have a contemporary art program. One almost feels that without contemporary art, they fear they might run the risk of being forgotten. Is this your impression?

Not at all. I really don’t think that Versailles would be forgotten if contemporary artists weren’t invited. However, I do think that programming contemporary art is a way to convince new audiences to come—and to keep coming back. What’s really striking is that you often see people who came for the contemporary art show rediscovering the whole of Versailles. This is wonderful for me. Contemporary art allows people to look at Versailles differently. But it’s always an addition, never a subtraction.

How are the artists selected?

The decision is taken by the president of the public establishment that is Versailles. I work closely with Alfred Pacquement. Jean-Jacques Aillagon worked a lot with Laurent Le Bon, who is now at the helm of the Musée Picasso. It’s a conversation between us, although in the end, it remains the president’s decision.

Your appointment in 2011 caused a bit of a scandal among curators and art historians in France. Do you think you’ve proven them wrong?

I didn’t experience it like that. Some people were skeptical about my appointment, but not all the curators and art historians in the country [were against it]. Others, including some of the most distinguished among them, also supported my appointment and they helped me to deal with the criticism I received. I came here to do a job and I hope the work I have accomplished has proven I am worthy of my position.

Looking at the list of artists you’ve invited—Penone, Ufan, Kapoor—one can’t help but notice that these practices are much less spectacular than Koons’ or Murakami’s. How would you define your curatorial approach?

I think one has to keep moving and not always champion the same artistic forms. There’s also a demand from our audience, who wants to see different things. And indeed, we may deal with contemporary art differently in the future. Artistic creation during the Grand Siècle at Versailles was so strong that it allows for very different approaches. We had Koons’ baroque vision, and then Lee Ufan’s more minimalist offering, but both come from the same desire to engage with the place. All of the contemporary artists who come to Versailles—at least all of those I worked with—consider Le Nôtre to be a great artist. It’s fascinating to see how, through their eyes, this place─which can appear perfect at first─progressively reveals its mysteries.

For more Palace of Versailles coverage see Painting Missing from Versailles Palace, Versailles Gets Renovated, and New Jean Michel Othoniel Sculpture, and Artworks Vandalized in Versailles.

Catherine Pégard is a speaker at “VIEW: A Festival of Art History” at the Institut français du Royaume-Uni (February 27 – March 1, 2015)