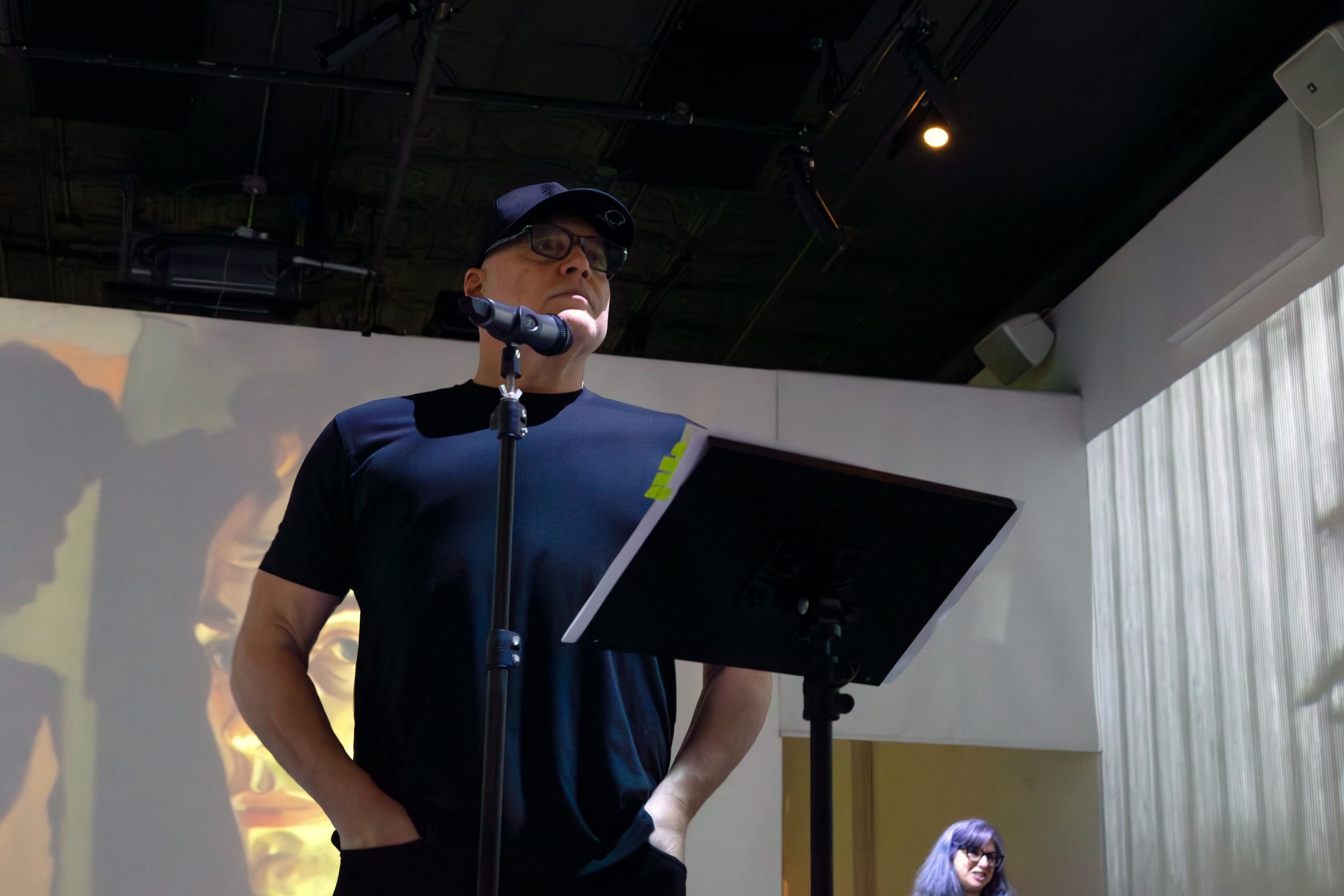

Vincent D’Onofrio stood before me with his eyes closed. His black baseball cap partially shaded his face in the dark room, lit only by the art that he and fellow actor/artist Laurence Fuller—as the duo Graphite Method—created. The visuals were projected on the walls of Lume Studios in Lower Manhattan in an April 2 performance titled “The Sparrow Experience.”

D’Onofrio spoke softly with his hands in his pockets. It was a meek appearance for an actor who once worked as a bouncer and bodyguard, whose deep voice fleshed out the art-loving villain Kingpin in Marvel’s Daredevil series, and whose presence loomed over Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), in which he played Pvt. Leonard Lawrence, his breakout role.

At times, it was difficult to sit and focus on the art. The viewer wants to watch D’Onofrio recite the poetry because he’s the actor, which distracts from the stop-motion-like vignettes on the walls around the viewer. Then, when listening to the words, it can be hard to consider his familiar voice in such a different medium.

Still, D’Onofrio’s reading of the poetry, which he often texts to Fuller from the sets of his films, is captivating and demonstrates how he earned a reputation for commanding the screen. And the poetry he and Fuller wrote is good, enhanced by the visuals, distracting thoughts aside.

Vincent D’Onofrio reciting poetry at “The Sparrow Experience.” Photo by Adam Schrader.

D’Onofrio and Fuller first connected over Twitter years ago, bonding over a shared interest in digital art. The pair officially launched their partnership at the 2023 Art Basel Miami Beach, where their joint works—digitally rendered vignettes paired with poetry written and read by D’Onofrio—were installed at an exhibition hosted by Web3 platform MakersPlace. Graphite Method’s first triptych was released as individual NFTs late last year.

Fuller and D’Onofrio describe most of Graphic Method’s poetry as “like a graphic novel” or noir thriller. There are recurring characters—a boy named Sheldon and an aging woman named Lady Bushwick—who appear in individual poems linked together by a plot, collectively titled “Sparrow.” Interspersed in last week’s performance were other poems that added texture to the overall show.

Though D’Onofrio often writes poetry while he’s working, he said it “doesn’t have to be” related to what he is currently doing on set. He recalled filming a scene recently where “I was actually crushing somebody’s skull while I was writing [poetry]. I had blood all over my suit and hands and I had to use baby wipes to get the blood off so I could text with my finger a couple of poems.”

When asked about his poetry influences, D’Onofrio said he is “too new and raw” to the medium to know. Later in the interview, he noted there are references to Edward Hopper in his work.

“I don’t really have any idea what I’m doing. I approach it like how I start developing a character for a film. I just start from all the experience that I have acting and it just starts to form on its own. There’s no particular influence,” he said. “I write exactly how I talk, which is mostly stream-of-consciousness.”

Vincent D’Onofrio at “The Sparrow Experience.” Photo by Adam Schrader.

Meanwhile, the visuals are created using photographs of Fuller, or that Fuller took, and feeding them through the artificial intelligence model Stable Diffusion to create the painterly looks in the short videos, giving everything a feeling of nostalgia and memory. The pair also shoots video—for example, for their work Penny. The older actor even purchased his younger partner a drone to film difficult shots.

“It’s as if a painting is being influenced by words, and changing because of words, rather than rather than actors within a scene or somebody narrating over a beautiful piece of cinematography,” D’Onofrio said of Graphite Method’s visuals. “We’re using the A.I. to morph our words for us in this kind of wild way.”

“A painting is like a dream. It’s a reimagining of reality reconstructed into a dreamscape and I think that is more inviting for the imagination,” Fuller said. “I don’t think that cinematography, just as with plain photography, gives the same sort of experimental experience.” Photographs, he added, “didn’t get to my subconscious as much as a painting did.”

Laurence Fuller reciting poetry at “The Sparrow Experience.” Photo by Adam Schrader.

As for the reading itself, D’Onofrio’s recitation carried a narrative tone like watching a man relay an Oscar-bait script over a dive-bar poetry reading. The performance of the work is a second thought, he explained, but he does think about how the words will inspire the accompanying visuals, which are “playing in my head.”

“I’m trying to keep with the tone of the piece but make it as raw as I can,” D’Onofrio said. “There’s other stuff where I do straight-up poetry stuff, but I also do it more reflective.”

Fuller said their different methods are “why we complement each other so well,” noting their different cultural backgrounds. D’Onofrio came up by way of the New York theater scene, while Fuller was classically trained. “If we both approached it from the same background,” said Fuller, “it wouldn’t work.”

Laurence Fuller reciting poetry at “The Sparrow Experience.” Photo by Adam Schrader.

The collaborators’ shared acting backgrounds didn’t just heighten their performance at the exhibition. To Fuller, such performances also lend new dimensions to the art of acting.

“In our time, actors are often overlooked as artists, and the craft of acting itself is sort of on this precipice of plunging into an abyss of social media and garbage. To honor the craft in the context of art history has barely been done at all,” Fuller said. Still, he points to Matthew Barney’s six-hour-long art video River of Fundament (2014), starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and Paul Giamatti, as an example when actors have been “welcomed into the canon of art history.”

D’Onofrio, for his part, said his collaboration with Fuller is just getting started: “One of the things I like about working with Laurence is that I’m open to anything that Laurence gives me.”

“The last thing that I want to do is claim to know what I’m doing,” he said. “All I’m doing is writing and collaborating with another artist and we’re just putting stuff out.”