Photo via: Kristoff

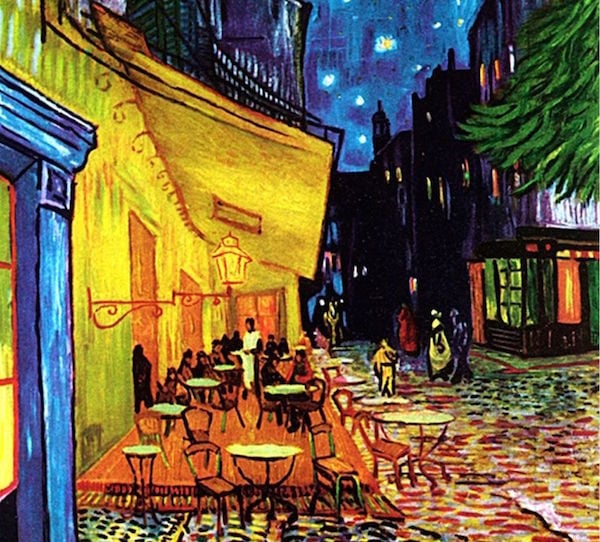

The latest Dan Brown-style conspiracy theory to hit the art world suggests that Vincent van Gogh might have hidden a homage to Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495-98) within his masterpiece Café Terrace at Night (1888). Indeed, a close study of the painting reveals that the main characters include one central figure with long hair surrounded by 12 individuals, plus a figure departing in the shadows. Does it sound like a familiar scenario?

For independent researcher Jared Baxter, it does, and it’s just the tip of the iceberg of a number of religious symbols concealed in van Gogh’s late works.

Baxter, who recently gave a lecture on the topic at the Dutch Association of Aesthetics, believes that the composition echoes the portraits of Jesus, the Apostles, and Judas in a number of historical depictions of The Last Supper, particularly in Da Vinci’s version. (See Da Vinci Restoration Project Reignites Conspiracy Theories.)

According to Baxter, around the time that van Gogh crafted Café Terrace at Night, he wrote to his brother Theo, referencing the painting and claiming that he had a “tremendous need for, shall I say the word—for religion.”

Furthermore, Baxter—whose theory is backed by a number of experts, including the art historian Bill Kloss—adds that a number of crosses feature in the painting, most crucially one formed by the muntin of a window above the central, longhaired figure, who is wearing what appears to be a white tunic (is it Jesus, or is it the café’s waitress?).

As far-fetched as this might seem, Baxter is not the first one to suggest that van Gogh’s religious leanings featured heavily in his artistic production.

In the 1990s, Japanese art historian Tsukasa Kodera published a number of books studying van Gogh’s use of Christian symbols, referencing, among others, the painting The Sower (1888), where the setting sun sits behind the painting’s subject as a halo.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Sower (1888)

Photo via: WGA

In 2004, UCLA professor Debora Silverman published the book Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art, where she wrote that: “van Gogh’s art had evolved by 1888 into a symbolist project that can be called ‘sacred realism’.”

Baxter was compelled to dig into the work of the revered Impressionist after hearing of a string of discoveries about van Gogh, which are reshaping the way we see both the Dutch master and his oeuvre.

The most surprising of these revelations came courtesy of Pulitzer Prize-winning authors Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, who, in their biography Van Gogh: The Life, claim that the painter didn’t commit suicide, as was previously thought, but that he was killed in the fields of Auvers by accident, by a group of youths brandishing a pistol (see Was van Gogh Killed? New Research Says He Was Shot).

Other controversies include the publication in 2009 of the study Van Gogh’s Ear: Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence, by Hamburg-based academics Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans, in which they argue that it was Gaugin who severed van Gogh’s ear during a heated argument. An accident the artists decided to silence.

Also, in 2011, Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum announced that a 1887 portrait from its collection thought to be a self-portrait, was in fact a portrait of the artist’s brother Theo.