Opening a letter may seem like a straightforward task, but that’s only in the age of mass-produced gummed envelopes, first invented in the 1830s.

For hundreds of years before that, many people relied on “letterlocking,” sealing their mail with a sequence of elaborate creases, folds, tucks, and slits. There were hundreds of different ways this could be deployed to secure mail from prying eyes.

Now, a team of 11 scientists and scholars has revealed a new virtual-reality technique for unlocking these antique missives without physically opening them in the Nature Communications journal, starting with a more than 300-year-old Renaissance-era letter penned in Lille, France.

“We really need to keep the originals,” the article’s lead author, artist, letterlocker, and MIT conservator Jana Dambrogio, told the New York Times. “You can keep learning from them, especially if you keep the locked packets closed.”

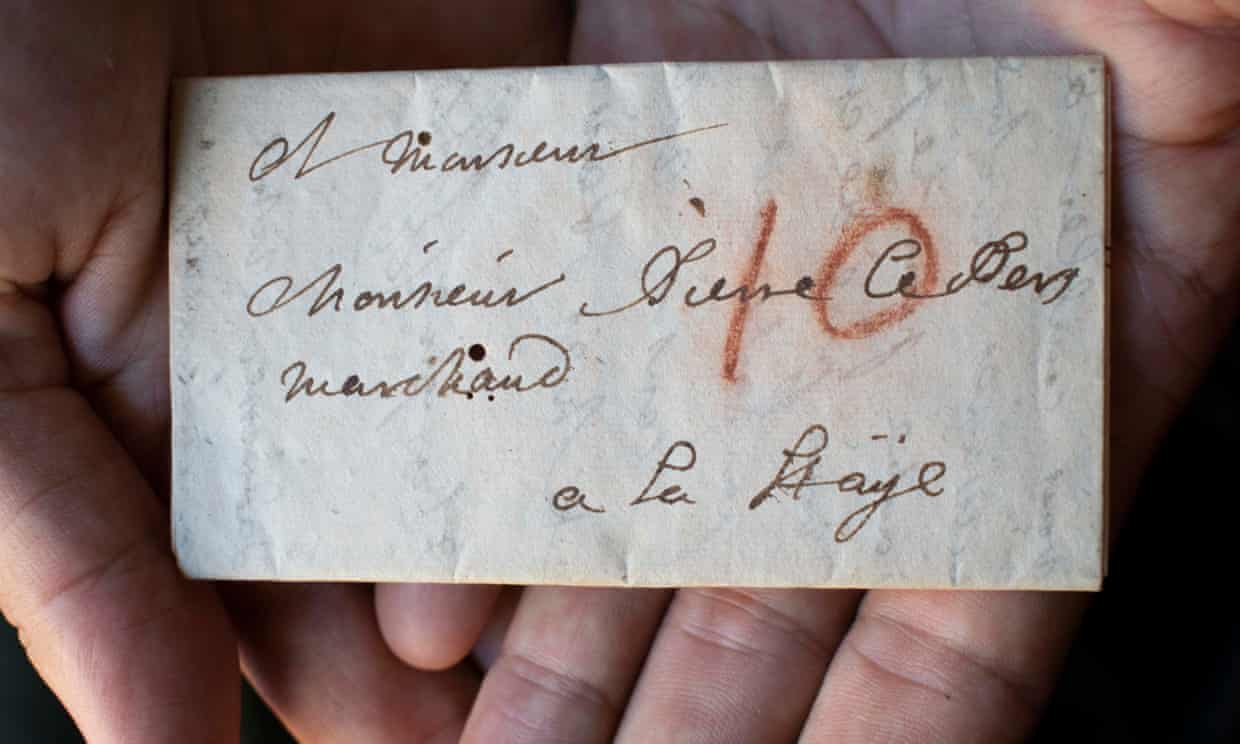

Virtual unfolding algorithms allow us to read an unopened letter with a paper lock from the Brienne Collection in The Hague, Netherlands. Photo courtesy of the Unlocking History Research Group archive.

The publication presents research conducted by Dambrogio and the rest of MIT’s Unlocking History Research Group Archive, a team up of conservators, historians, engineers, imaging experts, and other scholars.

“The power of collaboration is that we can combine our different interests and tools to solve bigger problems,” Martin Demaine, the artist-in-residence in MIT’s department of electrical engineering and computer science, told MIT News.

The first step to a virtual opening is to conduct a type of imaging called X-ray micro-tomography with a machine originally designed to study teeth.

Virtual unfolding algorithms allow us to read an unopened letter with a paper lock from the Brienne Collection in The Hague, Netherlands. Photo courtesy of the Unlocking History Research Group archive.

“We designed our X-ray scanner to have unprecedented sensitivity for mapping the mineral content of teeth, which is invaluable in dental research,” team member Graham Davis, a professor at Queen Mary University of London, said in a statement. “But this high sensitivity has also made it possible to resolve certain types of ink in paper and parchment.

Historic ink, typically high in metal elements, “shows up as a very bright region on the scan, kind of like the way that your bone would show up really bright on an X-ray,” one of the article’s authors, Amanda Ghassaei, told NPR.

Ghassaei and Holly Jackson, an MIT undergraduate student, developed an algorithm that analyzes the dense layers of text and paper to decipher the long-hidden words. (The open-source code is available on GitHub, and may also prove useful in reading tightly rolled scrolls, fragile books, and other historical texts.)

The first successful “opening” was achieved in 2016, when scientists read a letter that had already been partially unwrapped. Even without knowing how many times a locked letter had been folded, the algorithm can produce 2-D and 3-D images of the paper, both folded up and lying flat.

The Brienne Collection in The Hague, Netherlands, a postmaster’s trunk full of undelivered mail, including hundreds of locked letters. Photo courtesy of the Unlocking History Research Group archive.

“This is a dream come true in the field of conservation,” Dambrogio told the Wall Street Journal.

The newly deciphered letter was written on July 31, 1697, and is held in the the Brienne Collection, a 17th-century postmaster’s cache of 3,148 objects, including 577 unopened letter packets. But although the methods used to unveil the letter were extraordinary, its contents—a request for a death certificate—are mundane.

“Sometimes the past resists scrutiny,” the MIT team said in a statement. “We could simply have cut these letters open, but instead we took the time to study them for their hidden, secret, and inaccessible qualities. We’ve learned that letters can be a lot more revealing when they are left unopened. Using virtual unfolding to read an intimate story that has never seen the light of day—and never even reached its recipient—is truly extraordinary.”