Eight months ago, artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller got a big break. They had been trying for about a year to create a work of art about Leonard Cohen, who died last November, for an upcoming exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. But they couldn’t find the right recordings and the piece “wasn’t working how we wanted,” Cardiff says.

They had envisioned a kind of interactive sound machine that would allow the public to hear one of Cohen’s poems each time they pressed a key on a keyboard. After months of frustration came a surprise intervention: Cohen’s manager gave the artists access to sound files of Cohen reading nearly 200 poems from his collection Book of Longing, which he recorded himself.

The recordings had never been published and they felt surprisingly intimate. “It was like opening a magic box,” Cardiff tells artnet News. “You can hear his stomach rumbling [and] planes going over his studio.”

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s The Poetry Machine (2017). Courtesy of Luhring Augustine, New York; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Koyanagi Gallery, Tokyo. All poetry written and performed by Leonard Cohen from Book of Longing, published 2006 by McClelland and Stewart. Courtesy of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Cardiff and Bures Miller used the recordings to create The Poetry Machine (2017), one of more than a dozen commissions included in a major exhibition about Cohen’s influence at the MAC Montreal in Canada (until April 9).

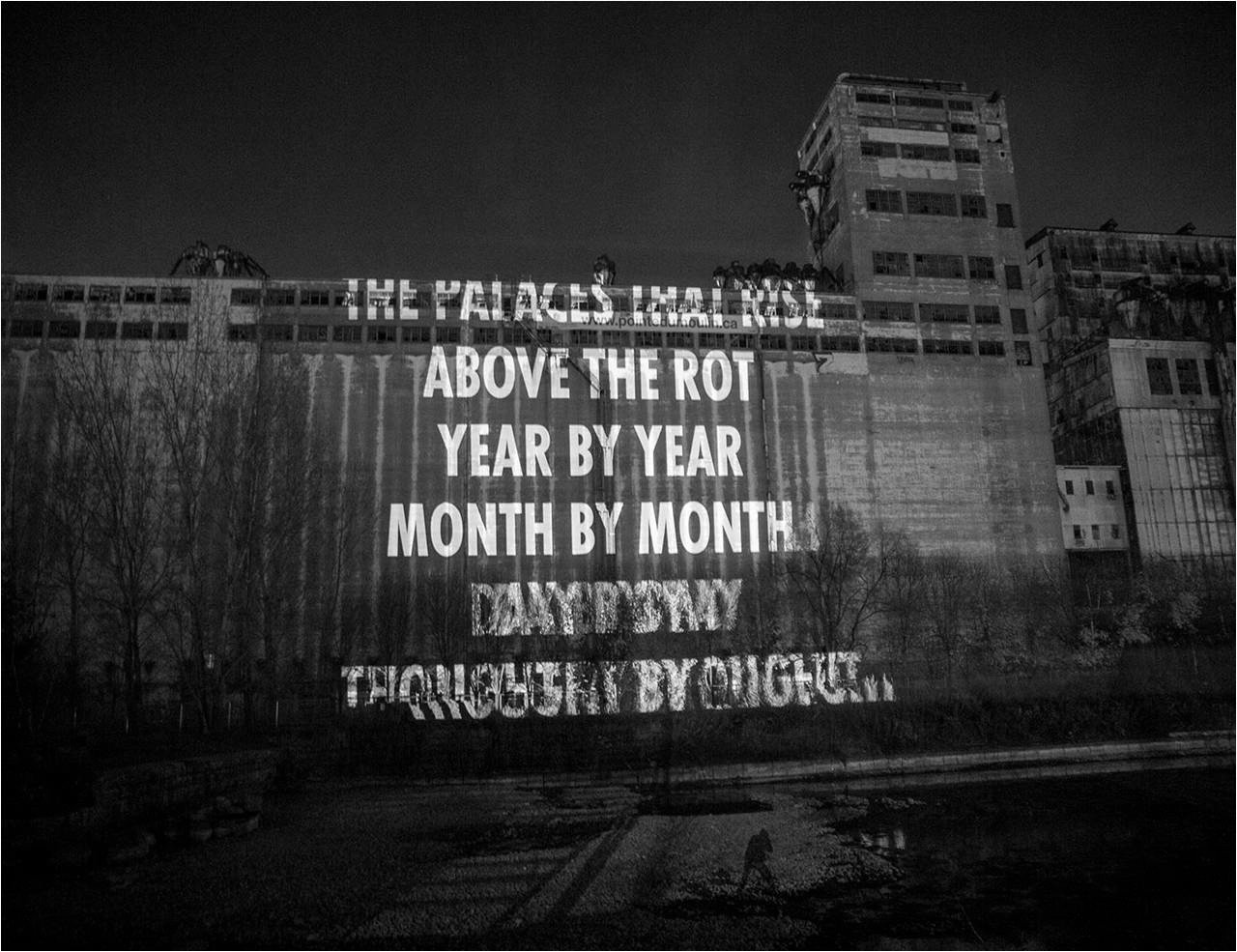

The show—which also includes new work by artists like Tacita Dean, Taryn Simon, Thomas Demand, and Jon Rafman—is the first museum exhibition devoted to the legacy of the beloved writer, musician, and Montreal native. To mark the exhibition’s opening, Jenny Holzer projected phrases from Cohen’s poems and songs in French and English on the facade of a former silo on Montreal’s waterfront last week.

The show, which takes over six galleries at the museum, was organized to coincide with Montreal’s 375th anniversary celebrations.

George Fok’s Passing Through (2017). Courtesy of the artist and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

The project had been in the works for about a year before Cohen’s death last November. “What began as an ardent celebration and affectionate tribute became a more solemn and commemorative exercise,” says the museum’s director, John Zeppetelli. “I see people weeping in the show all the time.”

Many of the works seem custom-made to pull at the heartstrings. The Los Angeles-based filmmaker Zach Richter created a virtual reality work in which a figure the same height as the user emerges from the dark and sings Cohen’s song “Hallelujah.”

The artist Michael Rakowitz, a longtime fan of Cohen, created an installation that delves into the Jewish musician’s relationship to Israel and Palestine. Also included in the show is a letter from Rakowitz to Cohen about how much he admired the musician’s work, which he wrote on Cohen’s own typewriter. (Rakowitz had bought it some years earlier.)

The South African artist Candice Breitz, meanwhile, held an open casting call for hardcore Cohen fans in Montreal over the age of 65. She selected 18 lucky amateur singers and recorded them performing Cohen’s 1988 album, “I’m Your Man,” a capella.

Candice Breitz, Stills from I’m Your Man (A Portrait of Leonard Cohen) (2017). Courtesy of Goodman Gallery, Kaufmann Repetto + KOW, and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

When the museum first approached Cohen about the show, it didn’t take long for him to agree to give artists access to his archives and music. “We said, ‘We don’t want to do a show of your record covers and fedoras, but to understand how your five decades of literary and musical output might have influenced generations of artists and filmmakers,’” Zeppetelli recalled.

The museum director says that he has been struck by how intimate the galleries feel, despite the fact that many of the installations created for the show are monumental. “I feel like that is really Leonard’s spirit,” he says. “Leonard is incapable of summoning grandiosity or pomposity. He’s never, ever banal.”

Leonard Cohen. © Old Ideas, LLC.

Leonard Cohen – Une brèche en toute chose / A Crack in Everything is on view until April 9 at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.