Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum has for the first time published information on its website about the controversial father and son who founded the museum.

As noted in history books but never previously studied or put forth by the museum, both William Thompson Walters (1819‒1894) and his son Henry Walters (1848‒1931) were avid supporters of the Confederacy. William was involved in the first fatal clash in the Civil War and supported a secessionist party; Henry commissioned two monuments to Confederate figures that were only recently removed from the public eye.

The family also worked in Baltimore’s banking and railway businesses at a time when the city was a key route between the North and the South. Thus, the Walters family benefited from industries in both regions and, as a new biography on the museum’s website explains, “participated in creating, promoting, and perpetuating oppressive social, economic, and political structures with legacies that continue to create inequity and inequality today.”

The father and son made no secret of their allegiances. The elder Walters commissioned for the city a portrait of Roger B. Taney, the chief justice of the Supreme Court who delivered the majority opinion in the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which ruled that Black Americans could never be citizens of the United States. It remained on view until 2017. His son funded a monument in Wilmington, North Carolina, to George Davis, who served as attorney general of the Confederate States. It stood until June 2020.

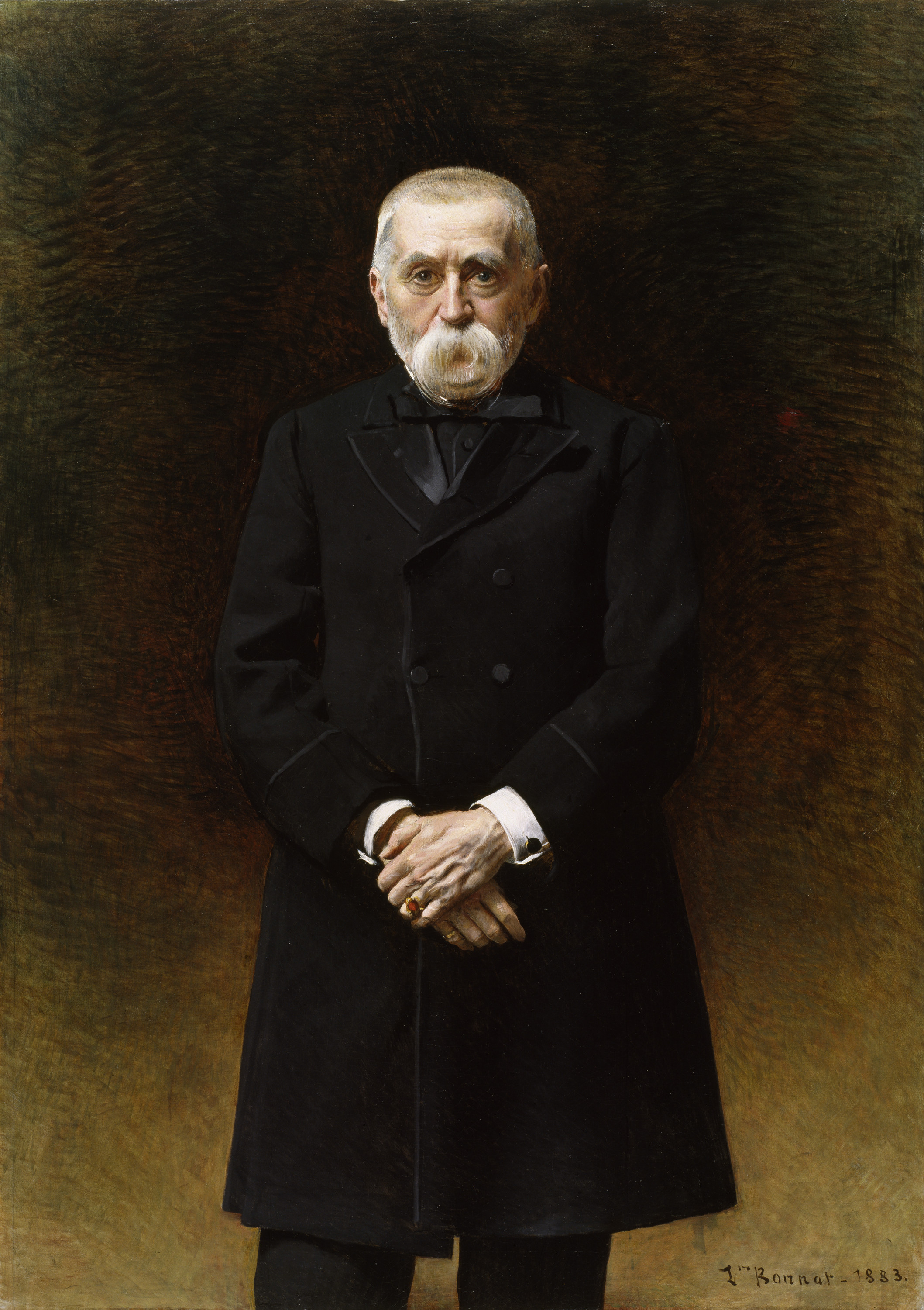

Portrait of Henry Walters by Thomas Cromwell Corner.

“We were looking at the available information through the lens of art collecting and philanthropy,” the museum’s executive director, Julia Marciari-Alexander, told Artnet News, “but only now have we begun to think about their sociopolitical activities and how those interact with their art collecting and philanthropy. There is a lot more to uncover and to see. Sometimes you acknowledge facts but you don’t delve into them.”

The museum recently devised a new diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion plan that includes developing more ambitious school and teacher programs, improving pay equity, and supporting “ladders of opportunity to museum careers.”

“It’s really important to think about how we as a field can unpack our history as institutions that were created by the collections of individuals and institutions that are themselves part of a system that promoted systems of oppression and white supremacy,” Marciari-Alexander said.