“Blackness was [and is] part of a larger world,” the art historian Kellie Jones said last week, during her keynote address to the symposium to mark the opening of the Brooklyn Museum’s pioneering exhibition of black feminist art, “We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85.”

Jones was commenting on the work of Elizabeth Catlett, featured in the show—but she could also have been commenting on the curatorial method of the show as a whole. What makes “We Wanted a Revolution” such a triumph of curatorial practice is how it goes beyond the celebration of its heroines in isolation to celebrate them as part of a larger world.

The exhibition brings together a diverse collection of artworks, from video art to sculpture to performance to photography and painting, from over 40 different artists. Side by side with this, it also features a wealth of ephemera and magazine clippings that contextualizes the works and the artists’ career within the larger historical and cultural movements of the time.

The overall effect is to reenliven a discussion on how the vitality of the Black Arts Movement was predicated on the incredible contributions of black women artists—both through their art and through their activist exploits.

The show’s curators, Catherine Morris and Rujeko Hockley, spent no less than three years working on the project, mining the Brooklyn Museum; the Brooklyn Public Library; the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University; as well as the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University in Atlanta, for artworks, letters, personal photographs, and much more. The curators carefully strategized the way the exhibition would be structured in collaboration with the artists in the show itself. The result is a showcase of their works with a particularly serious attention to historical context.

The exhibition opens with two large works, just outside the entrance of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. The first is Faith Ringgold’s For the Women’s House (1971), a large square oil painting depicting women of all races working in professions that were typically held by men: a doctor, a minister, a police officer, and president of the United States. Made for the woman inmates who were then housed inside the walls of the Rikers Island Correctional facility, the work was intended as a beacon of hope in an otherwise despairing environment.

Faith Ringgold, For the Womens House (1971). Courtesy of Rose M. Singer Center, Rikers Island Correctional Center. © 2017 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The second of these prefatory works is more abstract, but can be seen as about struggle in its own way: Maren Hassinger’s Leaning (1980), a series of short bundles of wire rope, frayed at both ends, all sitting on the floor at various angles. They give the impression of graceful movement, straining against an unseen weight.

Maren Hassinger, Leaning (1980). Courtesy of the artist. © Maren Hassinger. Photo by Adam Avila.

Both pieces, as the curators pointed out during the press preview, have been only rarely seen in public. They make a fitting introduction to a show whose theme becomes the recognition of the overlooked.

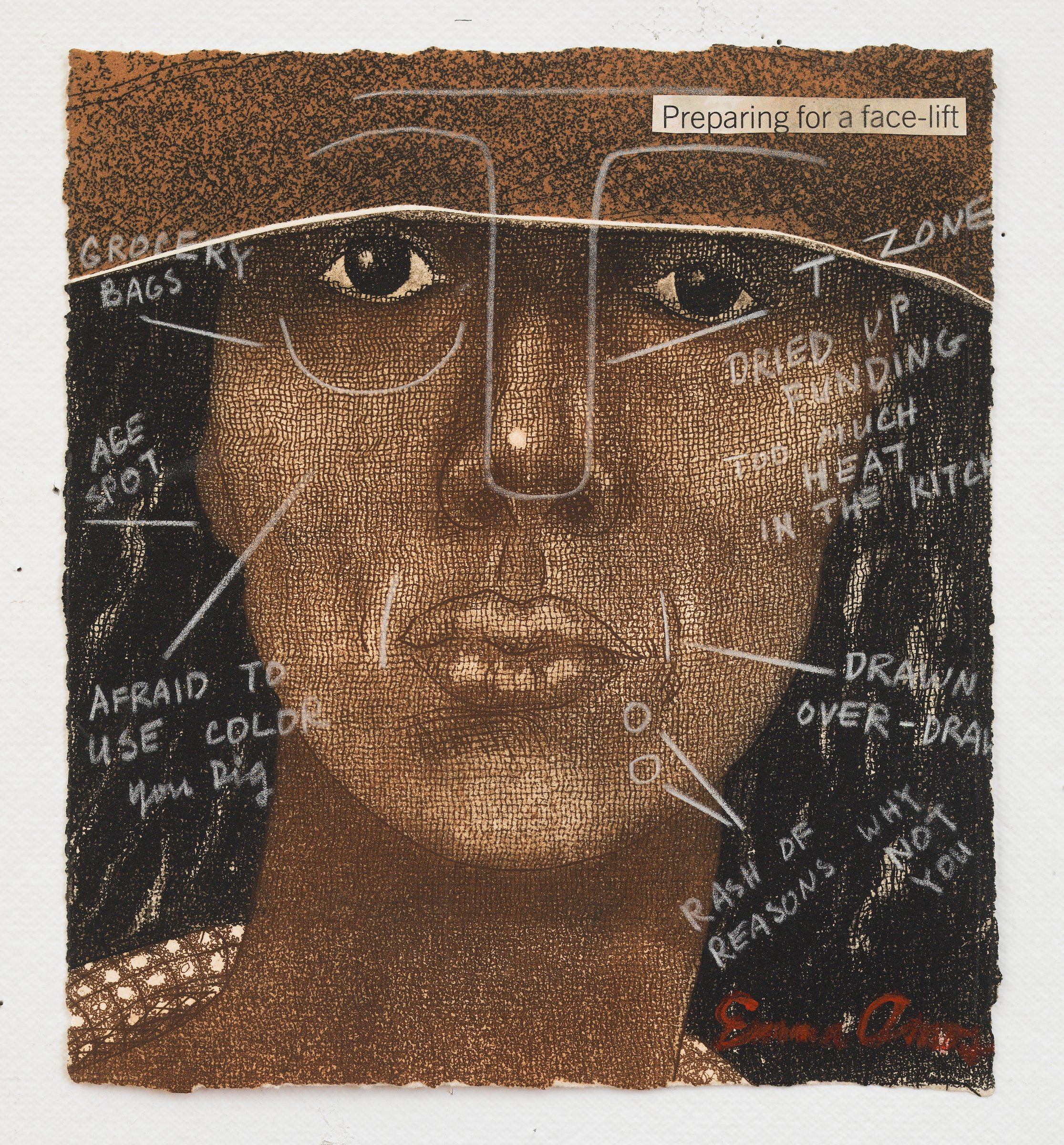

For instance, in the opening galleries, you are greeted by work by Emma Amos, the only women in the Spiral Group—an African-American art collective normally remembered for its famous members like Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence.

Jae Jarrell, Ebony Family (ca. 1968). © Jae Jarrell. Photo by Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum.

Another under-known figure is Jae Jarrell, a co-founder, with her husband Wardworth Jarrell and others, of the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), a Chicago collective that advocated for black visual artists. Jarrell’s dresses are a particular revelation of the show’s opening, 1960s section: Ebony Family (ca. 1969) and Urban Wall Suit (ca. 1969). Inspired by the vibrancy of graffiti-covered walls, she both made and wore these garments as markers of African-American pride and excellence.

Where We At Collective, Cookin’ and Smoking’ (1972). Photo courtesy Dindga McCannon Archives.© Dindga McCannon. Photo by David Lusenhop.

Further revelations come in galleries dedicated to black feminism, including attention paid to Where We At, founded by Dindga McCannon, Kay Brown, and Faith Ringgold, following the exhibition of the same name at the Acts of Art gallery in Greenwich Village in 1971. Works like McCannon’s Revolutionary Sister (1971) and Ringgold’s dynamic political posters, Committee to Defend the Black Panthers (1970) and People’s Flag Show Poster (1970), testify both to the powerful creative personalities nourished by the group and the causes to which they were attached.

Faith Ringgold, Committee to Defend the Panthers, 1970. Museum of Modern Art © 2017 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One of the more interesting aspects of this show, however, is the attention placed on the the actual personalities of the artists and activists around the work, as well as the social movements around them.

A good example is a gallery dedicated to the personality of Linda Goode Bryant, a filmmaker but also the founder of Just Above Midtown (JAM), a non-profit art space committed to supporting artists of color. The ephemera in this room showcases correspondence from Bryant, including, for instance, a letter written to Betye Saar inviting her to exhibit her work at JAM. The effect is to emphasize the labor of love that went into creating the networks knitting these figures together.

In the galleries dedicated to the 1980s, this sense of setting the art within its world continues. Here we see the early photo art of celebrated figures like Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems—but also, in one particularly moving example, a private photo taken by Simpson of the Rodeo Caldonia collective, a female African-American theater group based in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. The black-and-white image is stunning in its sense of behind-the-scenes intimacy.

Lorna Simpson, Rodeo Caldonia (Left to Right: Alva Rogers, Sandye Wilson, Candace Hamilton, Derin Young, Lisa Jones), 1986. Courtesy of Lorna Simpson. © 1986 Lorna Simpson.

“We Wanted A Revolution” is novel in its particular sensitivity to the women behind the art. This is, of course, a deliberate strategy in that these figures have, more often than not, been hidden from the public eye. It also is fitting in that so much of the art was actually about community.

The title “We Wanted a Revolution” has a mournful sound to it, of past optimism that didn’t quite arrive, perhaps representing the fact that the conversation started by these pioneers of black feminism has yet to be resolved. If a revolution has yet to arrive, however, at least this show can count as something else: It is a revelation.

“We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through September 17, 2017.