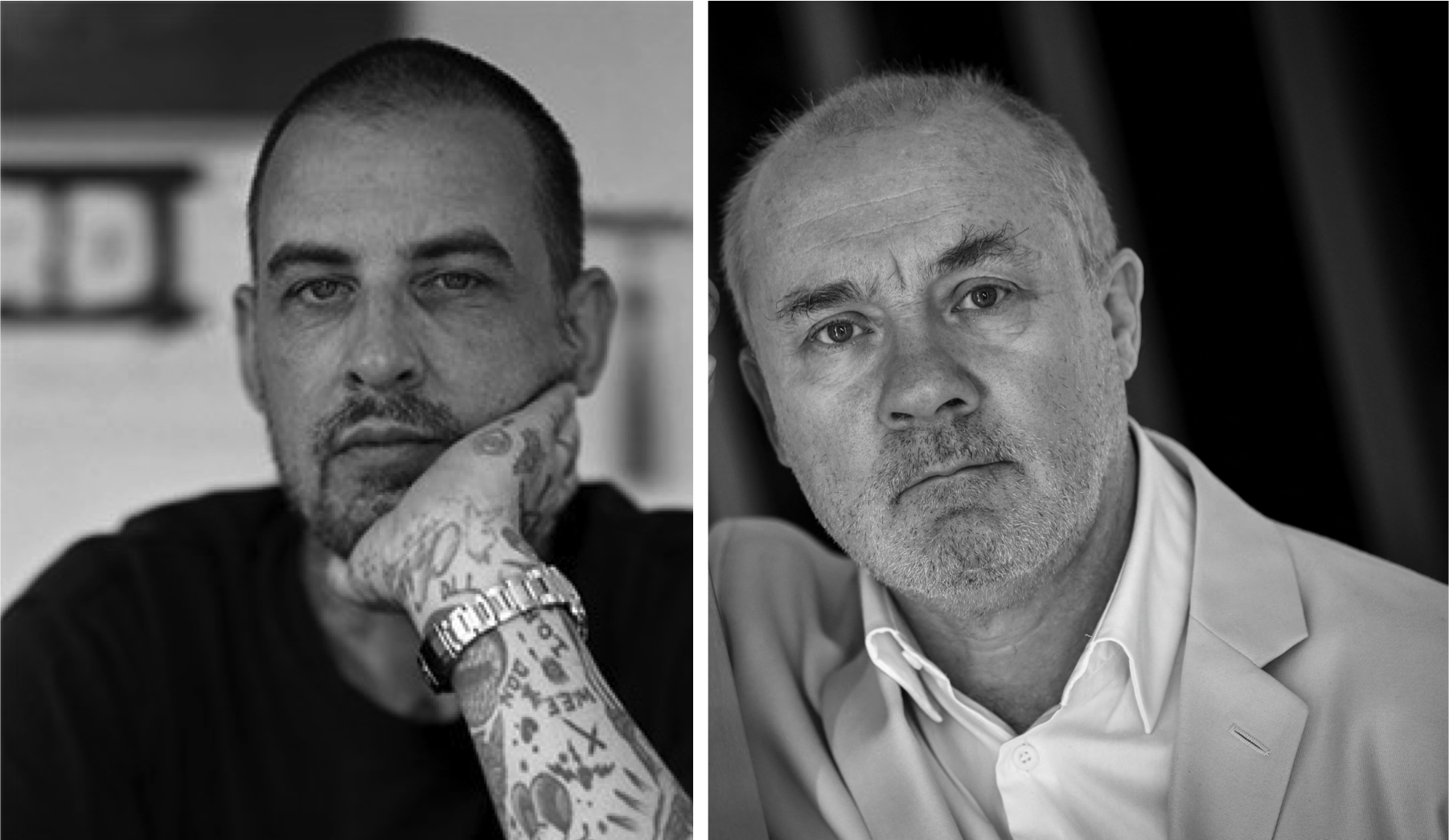

Even before Kanye tapped Wes Lang to design the t-shirts for his blockbuster Yeezus tour in 2013, Lang’s illustrations and paintings—a spiky synthesis of pop culture icons, Wild West mythology, and callouts to the giants of postwar art—had courted controversy and caught the eye of collectors, including none other than Damien Hirst.

No wonder: the two artists share a fixation on death and its opposite, living, that has only been heightened during the pandemic. Below, Hirst quizzes Lang about his creative process, art-world absence, around his upcoming show at Almine Rech Aspen.

Damien Hirst: As you know, I’m a huge Wes Lang fan, and I got some brilliant works from you. I’ve visited you in your sprawling studio in L.A. and seen your creative process in action, but what else can you tell me about your rhythms and rituals? What gets you out of bed in the morning? How do you find your pathway through the darkness?

Wes Lang: I paint in my studio in downtown Los Angeles, the one you visited me in, but—and I’m sure you can relate—I’m never not working in my brain. I typically have upwards of 30 paintings going at the same time. I like to have many things out in the studio so that if I’m not motivated by one body of work, I can move to another. It’s always been important to me that I don’t get stuck being an artist that makes one signature painting that looks like every painting that preceded it. The older I get, I hope you can see the cohesion among all my bodies of work if you take the time to sit and study them. I was incredibly inspired by what you did with the “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable” exhibition in Venice a few years ago. I recently started a new body of work that I plan to take the next five to six years on. It will be grand, ambitious, and—if I’m lucky—beyond what anyone thinks I am capable of.

Jay-Z and Wes Lang. Photo: Eric Minh Swenson/Splash News

DH: You’ve stayed pretty “off the grid” for the last decade. Why is that? Can you share a little about this recent period and what’s come out of it?

WL: I was living in New York and had been working with a gallery for many years. I wasn’t happy with the direction they were pointing me in and it didn’t feel like the support I needed anymore. So, I left them and took a gamble in the spring of 2011 by renting a room at the Chateau Marmont for six weeks. I took every penny I had and rolled the dice, living as though I was supposed to be there. That culminated in a one-night exhibition in the penthouse. It was wildly successful and totally changed my financial state. It showed me that I was right, that there was a world in which I could do things on my own terms. In 2012 I decided to move to L.A. permanently. I packed my car, drove across the country and moved back into the Chateau Marmont. I just knew I had to be here.

I remained without a gallery for a stretch, because it seemed like every time I picked up a paintbrush and made something, people wanted to come to my studio and buy it. I was able to make whatever I wanted and sell directly to my clients. I’m an introvert, really, but like all artists I want my work to make its mark in the world. I saw that I was going to be able to do just that if I could take complete and total control of what I was doing. That brought you into my life, and you gave me an opportunity that was and continues to be life-changing. I don’t know how much of this you want to be publicly known—and we can edit this out if you want—but you gave me an opportunity to make a large body of work over a period of time that freed me up to do what I wanted, without the necessity of a gallery. Having you believe in what I was doing at that point in late 2013 was really a clear eureka moment for me, and one that I will be forever grateful for.

DH: Say what you want, brother, we don’t need to edit anything out. I know you work at a crazy pace and make tons of art and you’re a hoarder. Do you have an Aladdin’s cave filled with lots of works that people have never seen before?

WL: Tons. At the time, social media was starting to take over the art world, and I really didn’t want to participate. If you look me up online, you don’t see much past 2009 besides little bits here and there—which I’m totally O.K. with, by the way. It’s how I want it. But now I have a big book coming out this year titled Everything that is being published by Rizzoli. It won’t reveal even close to all the works I’ve ever made, but it will be a well-selected survey of works from the 1990s until present day.

The flip side of working independently for so long is that very few of my paintings were seen publicly. A few years ago, at the exact moment when things became unmanageable, between both creating the work and running the business of selling my work, I mentally put it out there into the universe that I needed help. Almine Rech showed up at my studio in the latter half of 2019, and we started working together, which has been fantastic. I greatly admire what she’s done and why she does it. So it was just the perfect storm.

Wes Lang, Big Time Believer, 2021. © Wes Lang, courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Wes Lang Studio.

DH: Your work is full of symbols, especially symbols of death—Grim Reapers, skulls. But are they celebratory? A provocation? Where do you get your inspiration for all this iconography? What does it mean to you?

WL: They’re definitely a celebration. There’s nothing morbid about what I’m doing. I intend for my paintings to be joyful reminders of how lucky we are to be alive and to make the most of it while we have the opportunity to do so. The symbols are representations of the freedom we all strive for.

I’m also influenced by other artists, some of whom I unabashedly steal things from, as I’m sure you have. Art is a great, long conversation among the people who are willing to make it their life’s pursuit. Anything that I look up to is itself riddled with appropriation. I know, for instance, that you and I have a common interest in Francis Bacon. He made his whole life studying a very focused group of art by very specific people. All the great artists are influenced by their predecessors. As Jean-Michel Basquiat once put it, ‘You’ve got to realize that influence is not influence. It’s simply someone’s idea going through my new mind.’ If you can look to the past and learn, that’s how you can become great. Without any shame, I look to the great artists of the past to help me do just that.

DH: You’ve definitely never been afraid of appropriation, like with the Native American motifs. Has the way that debate has evolved in the last year or two changed your approach?

WL: My earliest memories are of toys, ads in the back of comic books, and novelty store catalogs. I would just collect and collect, holding onto these little talismans. They were so personal, I wouldn’t let anyone see them. I knew back then I would be an artist. To this day I still spend countless hours hunting for reference material. New characters may enter, but they are all still part of that same Wes Lang universe.

I’ve never looked at what I do as being provocative. So have I changed what I’ve been doing in the last couple years? No. I’ve never really changed what I do, and I don’t intend to. I am fighting my battle on the side of truth. We’re here with a purpose, to live and make the most out of this complicated and wonderful world while we can. That’s solely and completely what my work is about.

Wes Lang, No. 2 In E Minor, 2021. © Wes Lang, courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech. Photo: Wes Lang Studio.

DH: What are you most interested in creating these days? What’s driving your practice through this fucking weird world-ending period we are all living in and adapting to now?

WL: The last year and a half, with the lockdowns and deaths upon deaths surrounding us, has taken me on all different kinds of rollercoasters. I’ve been painting the world’s events more than I used to, but trying to find the positives amid the hellish mire we are swimming through. I feel that for artists, if you’re not paying attention to the situation and it’s not affecting what you’re creating, you’re not doing your job. Artists owe it to the world to speak about this situation. So there are works I’ve been making that are quite apocalyptic. I’ve always been obsessed with Pieter Breughel the Elder’s painting The Triumph of Death, ca. 1562–63. I’ve struggled with talking to this painting my entire adult life. I have always wanted to reinterpret it with my own version; however, it was impossible to truly tap into what Brueghel was doing because I didn’t live through the reality in which he painted it. But now I’m living through our own version of the plague. There’s a plague on the health of people, and there’s a plague on our minds happening at the exact same time. And a plague on the rights of people. There’s been no other time like now. On the other side of that, now that things are opening up and people are feeling better, my works are becoming extremely positive and bright and full of hope for a better world. Despite the scary aspects of it all, I’ve used this time as an opportunity to try to get even better at what I do. These days I feel unstoppable in the studio.

The building in Aspen housing pop ups by Lehman Maupin, Carpenters Workshop and Almine Rech. Courtesy: Lehman Maupin

DH: What can you tell me about your show in Aspen?

WL: I created a series of medium-to-large-scale paintings called “Endless Horizons.” I think they are all portraits of how I’m starting to feel, and how I want to continue feeling. I’ve been calling them propaganda posters for positivity. The words, images, compositions, and the colors in these paintings are very vibrant, playful, and lively. They feel like they are plugged into the wall; there’s a great electricity to them. That’s how I’m feeling in my brain and I’m just trying to put that across in the canvas. I’m pretty sure I’ve succeeded at it with this series. I’ve looked back to some of the earliest influences in my work, like Ellsworth Kelly, Martin Kippenberger, and Mark Rothko. Things that really blew my mind. So compositionally I was definitely influenced by them, especially in the backgrounds. Something that may strike people as “new” is actually something I’ve been doing forever, which is the use of lettering as opposed to handwriting. In my late teens I was a sign painter, and the only college course I ever took was a lettering and layout class at a community college in New Jersey in 1991. It taught me how to have a steady hand, and how to pull good lines and curves. For some reason with these paintings I felt that I needed to use fonts. So there are bold, mantra-like statements and phrases: “There Is Magic… Here It Is… And It Is Just So… Wonderful… Only This Moment Is Real, Where The Light Enters You… .” If you allow yourself, you will see something bright and new and positive, and if you know what I do you will know it’s rooted in practices that I’ve been doing for many years, and hopefully will be doing for many more years to come.

DH: You’ve spoken about how some of your artistic practice is rooted in studying and practicing the Tao Te Ching, using it as a sort of manual for living life. How does this play out in your work?

WL: I want my work to make people feel good, but that’s only going to happen if I feel good.

The Tao Te Ching really is the only thing that I’ve ever found that makes real sense to me. It helps you shed the detrimental sides of your ego and allows you to push yourself to be exactly who you want to be. Most of time we look to outside sources to make us feel better instead of looking inside and understanding that everything we’ve ever wanted is already there, and really always has been. If you study the Tao and look at it with an open mind, you can understand that this world is set up for you to succeed if you let it. The more you try to push XYZ to happen for you, the less likely it is that it will happen—quite often it will produce the opposite result. The older I get, the more I let go and try to let the world show me what it is that I’m supposed to be doing. The attention you need is often markedly different from the attention you think you need.

“Endless Horizons” is on view at Almine Rech Aspen, August 27–September 12, 2021