“Something changed when Africans began to take photographs of one another: You can see it in the way they look at the camera, in the poses, the attitude,” essayist and photographer Teju Cole wrote in the New York Times earlier this year.

A recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York offers a chance to see exactly what Cole means. A collection of 80 photographs, negatives and postcards from the Met’s archive has been carefully compiled to form “In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa.” A century’s worth of photographs are on display, showing how African artists have taken the medium into their own hands.

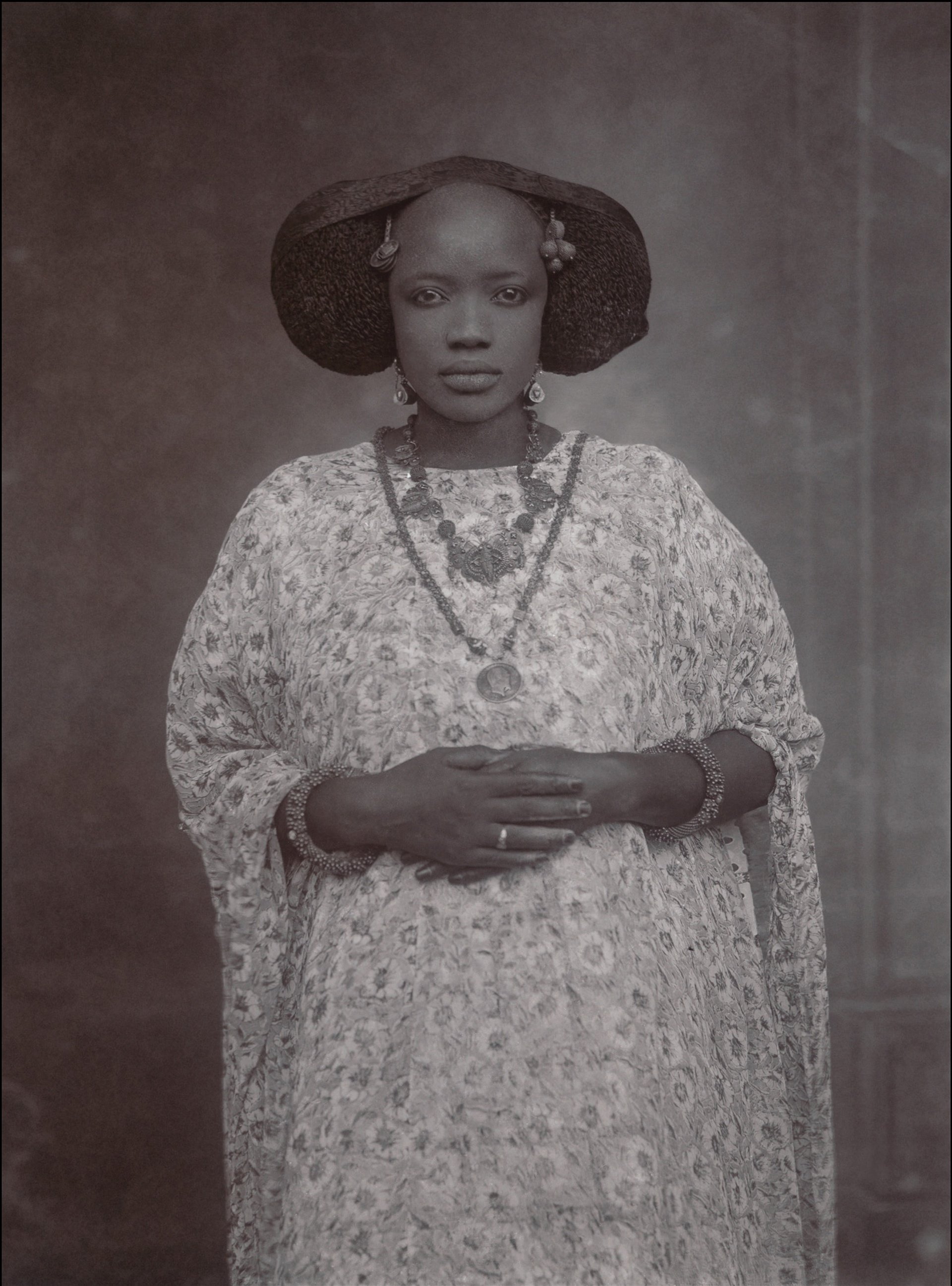

Images of fashionable women sporting traditional dress and formidable hair styles, and skinny boys in flared jeans make up the bulk of the work, in addition to self-portraits from the photographers, which were all taken between 1870 and 1970.

Seydou Keïta, Reclining Woman (1950s-1960s).

Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Two artists in the exhibition whose pictures of women are particularly striking are Seydou Keïta and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere.

In 2006, the New York Times chronicled the long and complicated quest for Keïta’s studio shots—a scandal pointedly marked by collector and fellow black-and-white photographer, Jean Pigozzi, reportedly shouting “I own Seydou Keïta!” across a crowded opening.

Some of Keïta’s best portraits document middle-class life of West African subjects in the 1950s and 1960s. In these images his sitters’ vivacity and the unseen but easily imagined colors of the clothes that they wear, are extraordinary.

Until the early 20th century, practically all photographic documentation of West Africa had been produced by white Europeans. “Those photographs, in which the subjects had no say in how they were seen, did much to shape the Western world’s idea of Africans,” Cole explains.

Seydou Keïta, Woman Seated on a Chair (1956-57).

Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

But once the camera was out of the hands of white Europeans and into the hands of black Africans, portrait subjects started to communicate their own story through the clothes they chose to wear and the poses they chose to adopt.

In Keïta’s photographs the women’s gaze penetrates through the two-dimensional shiny object on display, and through time and space as she holds your gaze. Her eyes are open and receptive, ready to start her own conversation with the viewer.

Seydou Keïta, Untitled (1959-60).

Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When he first started taking photographs, Keïta was working in his father’s carpentry shop. He used his bed sheet as a backdrop and the sun as his only source of light. Later, the artist hung more elaborate, pattered textiles for his subjects to pose in front of.

When artist Mickalene Thomas partook in a series conducted by the Met where contemporary artists speak about who they look to for inspiration, she discussed Keïta’s influence.

“I’m always looking at Seydou Keïta and thinking, ‘How did he do that?’ I studied as an abstract painter and was really excited about how these different fabrics collided but they made sense. They created chaos but then this quiet moment with this figure. The resting spot is her face, is her skin. You are looking at her, the softness of her lips, that pausing moment brings you to the gaze of her eyes and holds you there,” Thomas says in an interview with Culture Type.

J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Modern Suku) (1975).

Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere’s portraits of the mid-1970s take a different approach, honing in instead on women’s hair. The Nigerian photographer has two works in the show, both are of incredible and intricate hairdos, seen from behind.

These photos celebrate black womanhood by showing the unique, inventive hairstyles that challenge existing Western notions of beauty. The inventions that Ojeikere photographed are architectural and intricate, and go miles beyond practicality. As such they tell an intimate story about someone without ever revealing her face.

The personalities of Ojeikere’s women yell out of his photographs as loudly—sometimes even louder—than those of Keïta’s prints. His images will make you imagine the eyes of a lady who braided her hair into a noble crown and the smile of another who decided to twist her hair into fist-sized bunches.

In these shots, the women hold the power. They fill the frame with their bodies. Through their personal style, they create their own narratives to tell the viewer who they are.

Ojeikere started photographing the monumental and sculptural masterpieces that are these hairstyles, when he joined the Nigerian Art Council in the late 1960s. From here, the photographer built a portfolio so mighty it holds over 1,000 different architectural constructions, one more inventive than the next.

J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Mkpuk Eba) (1974).

Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Both photographers explore the potential of color and vibrancy in black and white. Apart from a few pieces that have hand-painted glass frames with leafy borders in reds, ochres and greens, all of the works in the show are black and white or sepia-tinged. Yet color and texture run rife throughout the exhibition. The photographers make it easy to imagine the bold colors in the patterns and textures of the checkered rugs that the West African women recline on and the way their jewelry catches the light as they move.

In their documentation of African women, their clothing and hairdressing, Keïta and Ojeikere bring the vitality of West African daily life to the surface.

“In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, August 31, 2015–January 3, 2016.