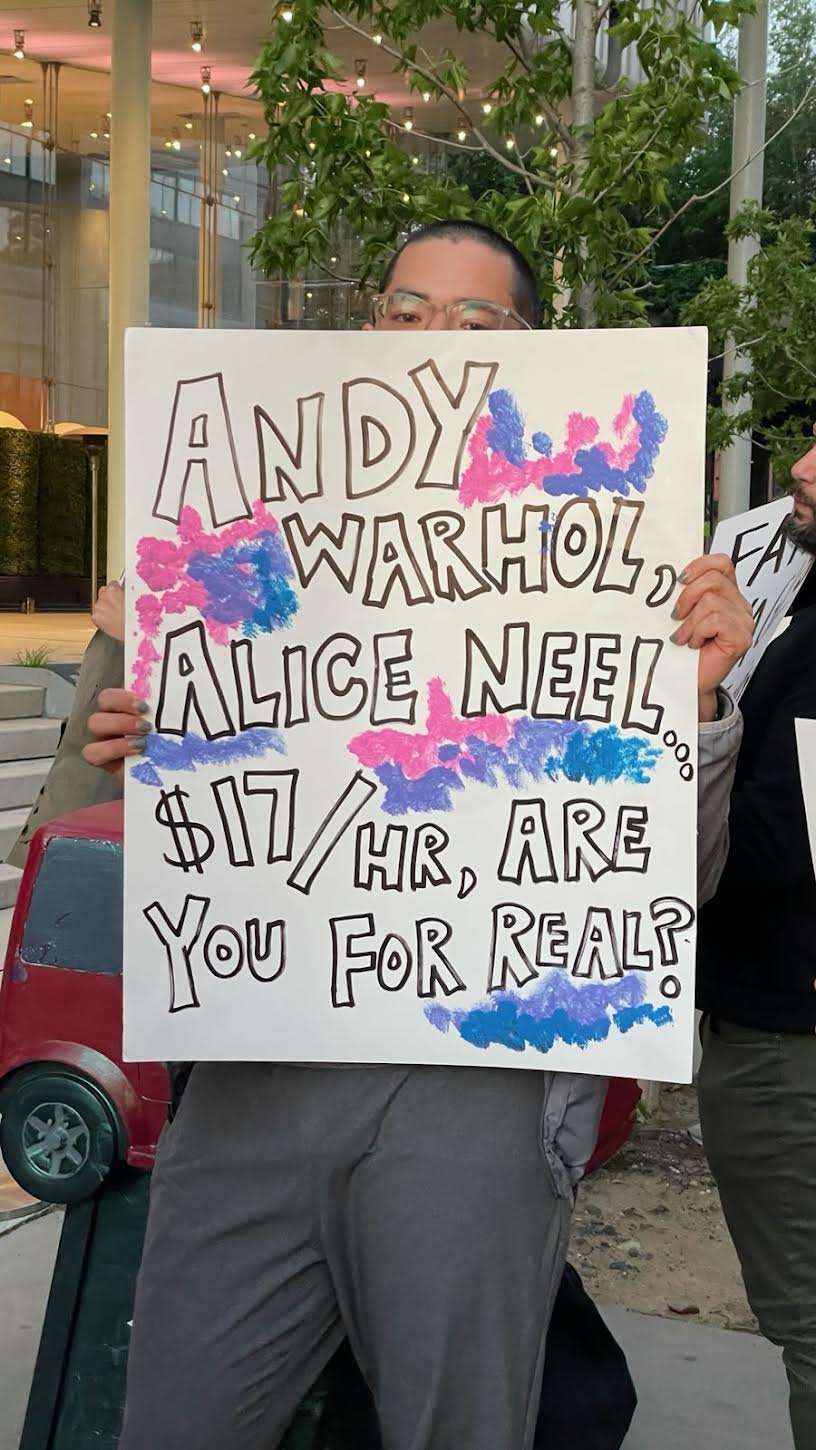

Events at the Whitney Museum of American Art this year have featured a consistent new guest: the museum’s union. Last night, at the museum’s annual gala and Studio Party, about 50 people turned out, standing on the curb with signs bearing such slogans as “LIVING ARTISTS LIVING WAGES,” “HONK FOR A FAIR CONTRACT,” and “WHITNEY WORKERS WANT FAIR WAGES” and banging on drums as guests filed into the museum’s lobby for a luxe dinner. Compared to the demonstration that followed the opening of the Whitney Biennial, it was a clear increase in participation, plausibly stemming from a wage offer on April 19 that fell far below the union’s proposal.

“It was so lowballed that it was insulting,” organizer Maida Rosenstein, the president of UAW Local 2110, told Artnet News over the phone. The union was pushing for improved compensation alongside renewed standards for job security and health and safety. What the museum offered was, “in some instances…actually proposing less than what people are making,” said Rosenstein. “It was tone-deaf in terms of what is going on in this whole sector of workers.”

Protesters outside the Whitney Museum of American Art. Courtesy of Maida Rosenstein.

The union is composed of educators, porters, visitor-services staffers, curators, and conservators, among others, and was voted in by workers on a 99 percent margin. “Staff turnover at the Whitney is a big problem,” explained Zoe Tippl, an exhibition coordinator at the museum. “Although we are passionate about the work we do, we need the Whitney to acknowledge our contributions and expertise through fair, competitive compensation. The museum needs to invest in Whitney staff as much as it invests in its exhibitions and collections.”

According to a release that the union sent out, the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, brings in a yearly salary of just above $1.1 million, and “the combined compensation for the fourteen highest-paid museum executives for the prior year totaled $4.5 million.” Signs on the street revealed that many employees, in contrast, earn $17 per hour, and claimed that they are unfairly kept as temporary employees, barring them from certain benefits—including union membership.

Derrick Charles, a membership assistant, said, “The museum gives lip service to supporting staff, but empty words don’t pay the bills.”

Though the museum blocked off the usual plate-glass fishbowl windows with screens for the evening, the sounds of the protest certainly made their way inside the dinner. Rosenstein surmised, “I think we got our message across pretty loudly.”