Post-meal dining tables are instantly evocative of companionship and revelry. For the Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri, who died on November 6 at the age of 94, the chaotic mess of stained cloths, crumpled napkins, and food-smeared plates was rich material for art making.

He began his “Snare Picture” assemblages in the 1960s, preserving the remains of meals consumed by friends, lovers, and strangers, before hanging them vertically on the wall. These pieces playfully suggest the connections, tensions, laughs, and momentary disputes that might have occurred during a meal. While the artworks could be seen as highly conceptual, there is an undeniable humor and lightness to them too.

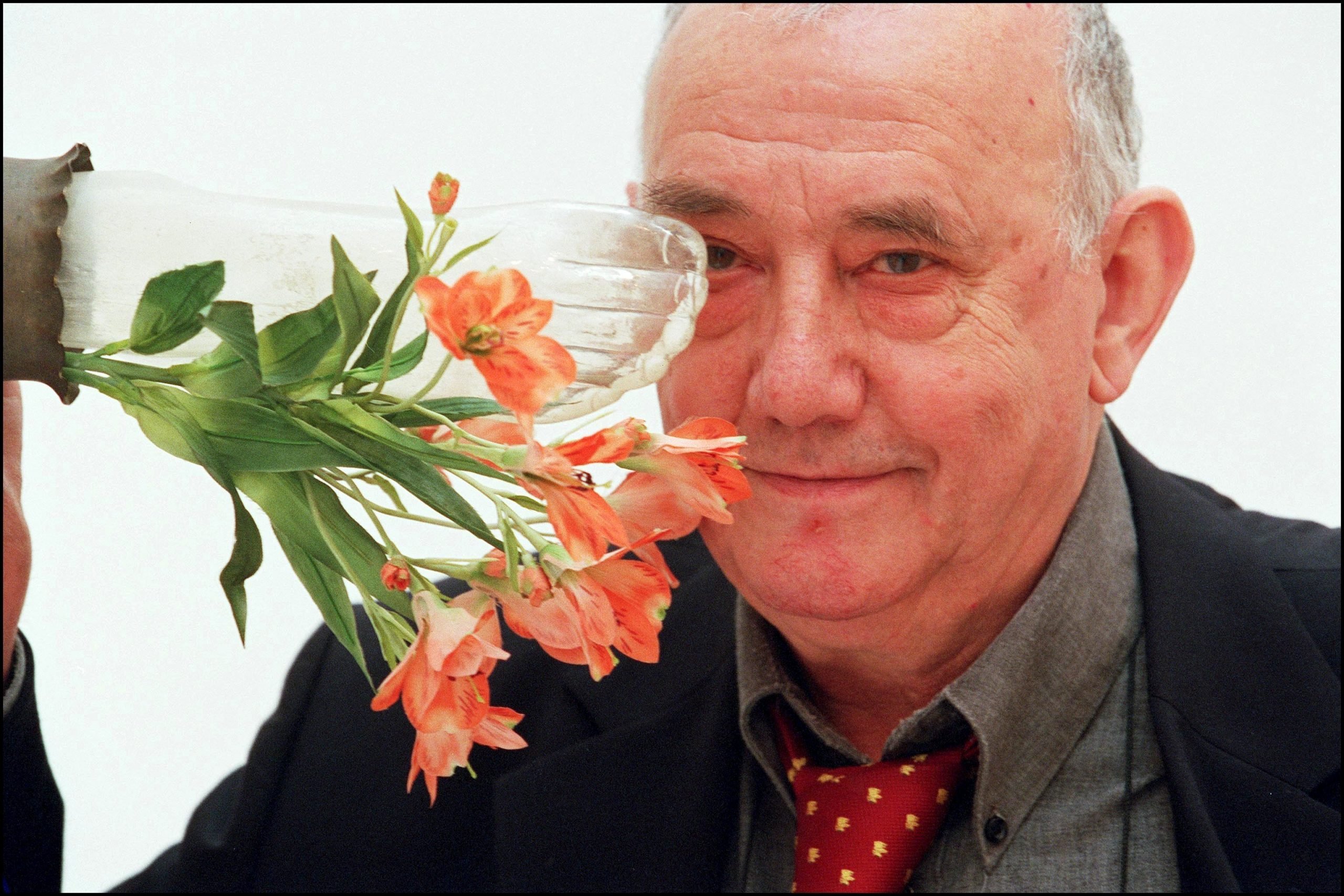

Daniel Spoerri, September 1964. Photo by Wieczorek/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the artist was a social and creative chameleon, working with iconic names such as Marcel Duchamp and Dieter Roth, and finding kinship with movements as diverse as Fluxus, Nouveau Réalisme, and Dadaism. “I decided to become an artist not because I had the gift of being good at drawing or sculpting, but because I could not do anything else,” the artist said. “It was a matter of survival. I could either kill myself or live that way.”

Spoerri, born Daniel Isaac Feinstein, was nomadic for much of his life, inhabiting various cities and islands around Europe. He was born in Romania in 1930. During the World War 2, along with his mother and five siblings, he moved to Switzerland where he was adopted by his uncle, the professor Theophil Spoerri, and changed his name. His father, a Jewish missionary who had converted to Lutheranism, was killed in a pogrom in 1941. “Everyone has something that drives them through life,” the artist would later say. “Being without a native land is the engine of my own.”

His first foray into the arts happened in the 1950s, when he studied classical dance. This led to him becoming the lead dancer for the State Opera of Bern. He met numerous artists from the Surrealist movement during this time and staged avant-garde performances such as Picasso’s farcical play Desire Trapped by the Tail. Spoerri connected his early poverty with the art he went on to make. “I come from a personal experience in which I had no money… and kept for weeks a piece of dry bread in a box, consuming it little by little with poor soups… When I had the money, I immediately associated art [with] food. Before the banquet comes food, then the kitchen, the restaurant, and then the ‘Eat Art’.”

Chefs look with awe at how Daniel Spoerri turned leftovers into a work of art, 2002. Photo by Raphael GAILLARDE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

“Eat Art” became a catchall for his many explorations of art and food. His first “Snare Picture” preserved a meal just consumed by his girlfriend, comprised of a wooden chair affixed to the wall with a narrow tabletop on its seat, covered in items including an open tin, an ashtray full of cigarette butts, and two hollow eggshells. Kichka’s Breakfast (1960) now lives in MoMA’s permanent collection. It is an inherently romantic piece, evoking the shared, messy intimacy of lovers, as well as their, at times, banal everyday coexistence.

“I had to wait decades before someone said ‘Oh, that’s beautiful!’ When I started, everyone said ‘Horrible! Who would put such a thing on the wall?’” He continued regardless; his most expensive “Snare Picture” preserving the remains of Duchamp’s meal sold at auction for just over $200,000 in 2008.

Spoerri was interested in capturing post-meal tables exactly as they were, leaving their final formation to chance rather than his own curation. “I only put a little glue on objects; I do not allow myself any creativity,” he wrote in the 1960s. These pieces exist somewhere between object and picture, hung on the wall as a painting might be, reflecting the symbolic potential of still lifes, yet maintaining an absurd presence as they jut from the wall, as though ready to spill over the floor.

A sculpture exhibition ‘Bad RagARTz’ by Daniel Spoerri. Photo by Keute/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

Spoerri explored the emotional potential of objects in obsessive detail. In 1962, his Topographie Anécdotée* du Hasard (An Anecdoted Topography of Chance) mapped all 80 items on his wife’s table, including his personal recollections of each one. His words about these objects expanded far beyond their physical presence, highlighting his travels, connections with other people, and his own context. This book was translated in 1968 by Roth, who added his own reactions to Spoerri’s words.

The artist found other creative ways of bringing food into the art world, sometimes cooking meals or selling pre-bought canned food in galleries. In the 1970s he went a step further, opening Restaurant Spoerri in Düsseldorf as an entangled project that collided art and food. Eat-Art-Gallery was opened upstairs and diners were invited to pay 1,000 Deutschmarks to have their table preserved as an artwork. Soon after, he published A Gastronomic Itinerary, a diary documenting his life on Greece’s Symi island, featuring recipes of local dishes. He followed this in the 1980s with a humorous collection of his fellow artists’ offal recipes, assigning different organs and parts, such as tripe for Roland Topor and fat for Roth.

Later in his career, he realized his pieces in bronze, and opened a sculpture garden in Seggiano, Tuscany, featuring works by over fifty artists including Nam June Paik, Jesús Rafael Soto, and Not Vital. Despite his collaboration with many high-profile artists, until his death earlier this month, Spoerri seemed more interested in the work than the trappings of fame. “I have always been sure, just like a research scientist… I was looking for something, the rest didn’t interest me,” he said. “I didn’t want to be famous, I sought answers to my restlessness, my insecurity, my issues, and questions that I ask to life. “