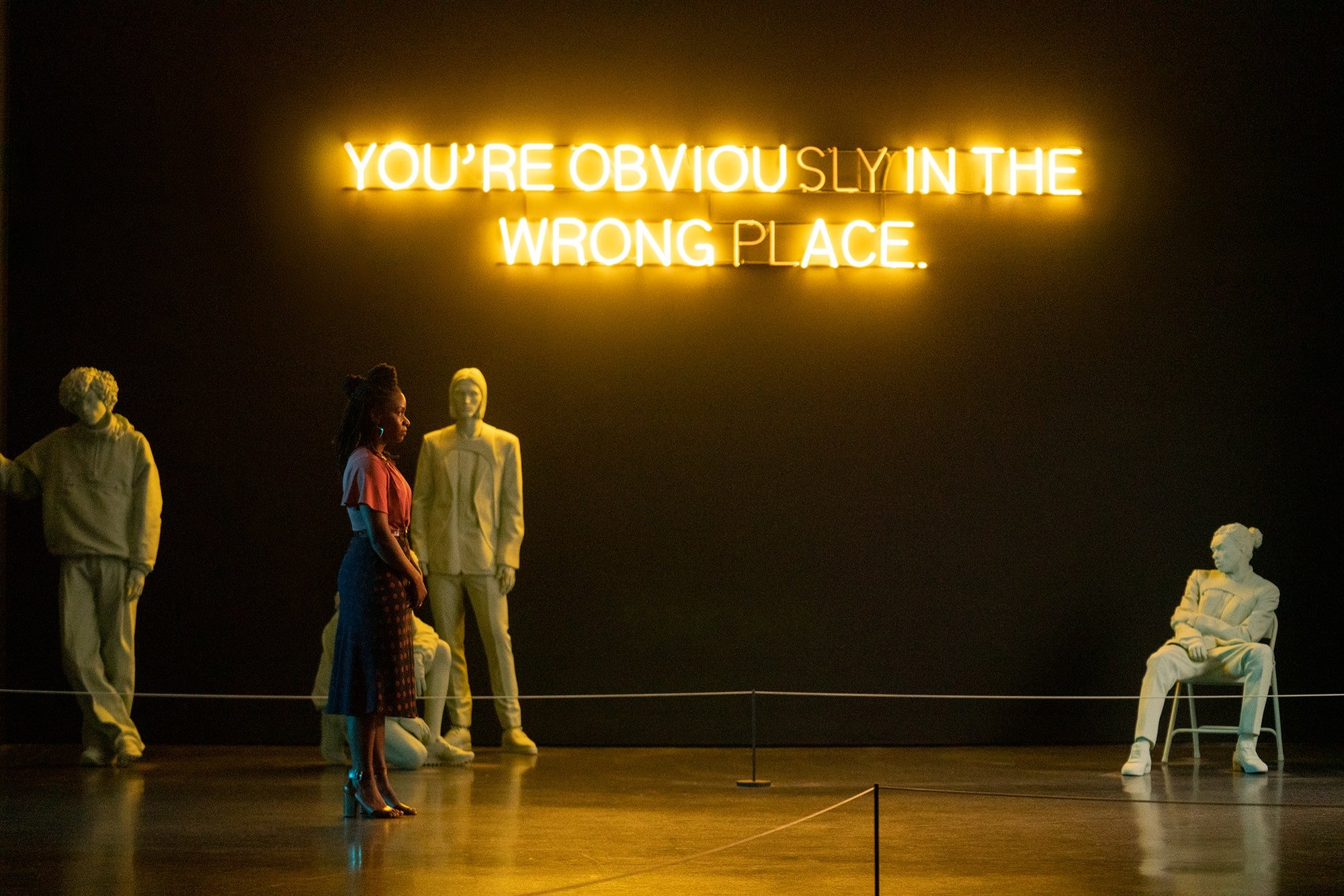

There’s a scene about a third of the way through Candyman, this year’s much-anticipated reboot of the 1992 classic, in which the film’s protagonist, a Black artist, defends his work to a white critic at a buzzy gallery opening. The critic doesn’t think much of his piece.

“It speaks in didactic, knee-jerk clichés about the ambient violence of the gentrification cycle,” she says sharply, then calls out his apparent hypocrisy in claiming such a narrative. “Your kind are the real pioneers of that cycle, you know….Artists descend upon disenfranchised neighborhoods to find cheap rent so they can dick around in their studios without the crushing burden of a day job.”

She’s both right and wrong in her accusation. The artist, Anthony, lives in a tony Chicago loft overlooking a neighborhood once defined by its affordable housing. But, we find out later, as people close to Anthony start dying off in grisly fashion, that he has roots in the area’s previous life, too.

By that point, of course, the critic—named, impeccably, Finley Stephens—has pulled a 180: Now she loves Anthony’s art. “All of a sudden,” she says, “your work seems eternal.” In a neat hat trick, Stephens has both articulated one of the film’s central preoccupations and enacted it: the cycle of gentrification, and who is responsible for or complicit in that process.

Yahya Abdul-Mateen II in a still from Candyman (2021). © Parrish Lewis/Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures.

Watching Candyman when it came out roughly two months ago, I found these moments ironic, as the film, directed by Nia DaCosta, is itself a kind of a gentrified version of the grittier—yet more elegant—earlier film on which it’s based. With its major studio distributor and $25 million budget, the movie is clearly aimed at a certain audience. It’s not the usual horror crowd, those who are happy to forgo overall polish for a few extra-gnarly scares, but a class on the hunt for a less spattered thrill—perhaps even one that delivers a frisson of self-implication.

To put it another way, it’s for people who would have seen Get Out a third time if they could.

This approach is not unique to DaCosta’s film. There have been a number of horror and thriller movies over the last half decade to adopt an art world milieu or cast an artist as a central character. Why are so many filmmakers turning to this trope? And what does that say about our industry?

Daniel Kaluuya as Chris and director Jordan Peele on the set of Get Out (2017). © Justin Lubin/courtesy of Universal Pictures.

For filmmakers, the appeal is easy to see. My colleague, critic Ben Davis, put it to me this way recently: “Art is this big symbol at the heart of culture, one that represents the ideal career you’re sold, one where you get to express yourself, but at the same time is also really close to the evil one percent. That kind of libidinal charge—something that you both desire and revile—is a perfect horror object.”

But in recent years, we’ve also seen a new breed of art-world horror flick—glossy productions like Candyman, which not only deploy art in the service of concept but also weaponize the baggage we bring to the industry of art. These movies derive their dramatic tension from the systemic horrors of real life, and the art world offers up a prepackaged metaphor for moral corruption. Whereas in previous decades, high schools, suburbs, and summer camps were the sites of sex, drinking, and bullying, for today’s audiences, the auction saleroom or white-cube gallery convey more modern types of sin: cultural appropriation, say, or the gentrification cycle; the way the wealthy elite push pedantry to reinforce systemic inequities of power.

They are, in essence, social thrillers, a genre put forth by director Jordan Peele, who coined the phrase to describe his 2017 blockbuster Get Out. “I was trying to figure out what genre this movie was, and horror didn’t quite do it,” he later told New York magazine. “Psychological thriller didn’t do it, and so I thought, Social thriller.” Scary movies have long used monsters and ghosts to symbolize society’s ills, but the social thriller cuts out the middleman, making those forces the villains themselves. In these movies, Peele explained, “The bad guy is society.”

A still from Get Out (2017). Courtesy of Monkeypaw Productions.

Peele built Get Out, which tackles liberal racism, around a Black artist. Chris, the main character, is a talented photographer who finds himself a target in an elaborate body-swapping scheme that puts white minds in Black bodies. Strapped to a worn chair late in the movie, prior to his operation, he meets his transplantation mate: Jim Hudson, a blind white art dealer, who selected him for a very specific reason.

Hudson explains that most people on his side of the operation table seek the physique of Black people, or the athleticism. “But please don’t lump me in with [them],” he says. “I could give a shit what color you are. No, what I want is deeper.”

The camera zooms in on Hudson’s face. “I want your eye, man. I want those things you see through.”

In a 2019 interview with Rolling Stone, Peele spoke to Hudson’s significance in the film. “For me,” the filmmaker explained, “the idea is that the guy who is the farthest from racist, the guy who is literally blind, still plays a part in the system of racism. And the way it manifests in that movie is, yeah, a guy who believes that the eye of this better artist, this Black artist, is what’s separating him from being a success or a failure.”

In true social thriller form, a real-life horror—here, the exploitation of a Black creative—is literalized: the dealer actually wants to assume the artist’s body, suppressing his soul into the “sunken place.”

Rene Russo and Jake Gyllenhaal in a scene from Velvet Buzzsaw. Image courtesy of Netflix.

A number of Hudson-esque figures have populated movie screens in the wake of Get Out. Clive, Anthony’s meddlesome dealer in Candyman (which was co-written and produced by Peele), fills a similar role: “I want the great black hope for the Chicago art scene of tomorrow,” he says at one point to Anthony, all but urging the artist to lean into racial stereotypes with his work.

Then there’s Velvet Buzzsaw, Dan Gilroy’s 2019 art world send-up, which is overrun with Hudsons. In that film, a recently demoted gallery director stumbles upon the dead body of Vetril Dease, a reclusive and troubled painter, in her L.A. apartment building. After a little snooping in his place, she smuggles a trove of beguiling artworks that she thinks will jump-start her stalled career working under a hectoring power dealer—even though, we later learn, Dease wanted them to be destroyed.

As word gets out about a hot new outsider artist on the market, various bad art actors start conniving how they can get a slice of the pie. A tumescent critic, Morf Vandewalt (another great name), plans to write the first definitive book on the dead artist. A curator decamps from a local museum (the “LAMA”) to become an art advisor, then snatches up a handful of Dease canvases on behalf of her client and strong-arms her former institution into hosting a show of his work. Even an art handler takes his shot, attempting to pilfer a few of the paintings before putting the rest in storage.

Toni Colette in Velvet Buzzsaw. Image courtesy of Netflix.

Eventually, all of these characters—and everyone else who tried to exploit Dease’s legacy for profit—are attacked and killed by the artworks around them. The critic is knocked off by an animatronic “hobo” robot (surely an overt nod to Jordan Wolfson’s Female Figure), the advisor is torn limb from limb by an experiential sculpture, and the art handler is devoured by monkeys who emerge from a painting.

Of the central characters, only three are left standing, all innocents within the movie’s moral calculus: a browbeaten gallerina and a pair of artists who admire the purity of Dease’s vision. Money’s stranglehold on creative expression is at the heart of the satire here.

“I was interested in exploring the uneasy relationship between art and commerce in all arenas of entertainment in today’s world,” Gilroy told Artnet News upon the film’s release. “I feel strongly that the quality of a work shouldn’t be judged by the volume of social media engagement, or the number of people who went and saw it the first weekend, or the amount paid at Sotheby’s.”

Amy Adams as a soulless art dealer in Nocturnal Animals. © Merrick Morton Universal Pictures International.

Tom Ford’s 2016 film Nocturnal Animals isn’t about exploitation, per se—not in the way that Get Out or Velvet Buzzsaw are, at least—but the film opens with a tasteless example of it. From the opening credits comes up-close footage of obese women dancing naked with pom poms and batons. But then the camera pans out, revealing that what we’re actually seeing are video artworks in a gallery exhibition. It’s not the movie that’s salacious, you see, but the art world setting in which it takes place. (I’m not so sure the film pulls off the maneuver.)

Of the films mentioned here, Nocturnal Animals, based on a 1993 novel by Austin Wright, is no doubt the outlier. For one, it’s not really a social thriller; in fact, it’s barely a thriller at all. But its adjacency to the art world is worth pointing out. In a departure from the book, Ford’s screenplay makes the main character, Susan, a woman grappling with the hurtful misdeeds of a former life, into a high-powered art dealer. The profession embodies her personal dilemma: perfection on the outside, sin on the inside. The filmmaker was looking for a symbol of soullessness, and he found one in art.

Candyman located something similar in its setting, as did Velvet Buzzsaw; Get Out got there indirectly. In all these films, the art world and its power dynamics stand in for a litany of specific fears that—not coincidentally—bear a strong resemblance to those animating society at large. But perhaps there is another, deeper reason that filmmakers are turning to this trope. One of the scariest things about the art world is its own ambivalent relationship to the structures that sustain it. It’s the classic kind of maddening logic you’ll find in a lot of horror movies: you’re screaming for help, but no one seems to notice.