Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, some opinionated detective work on a late-breaking auction development…

NO RESERVATIONS

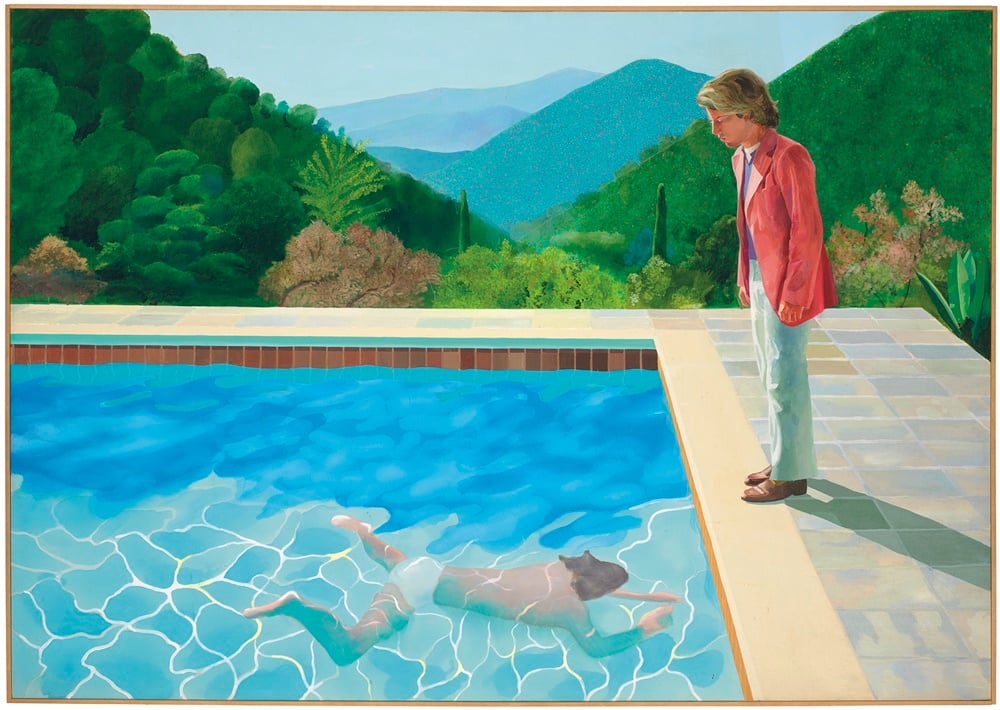

On Friday, Josh Baer reported in his email newsletter the Baer Faxt that Christie’s would offer David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972), the marquee lot of its upcoming post-war and contemporary evening sale in New York this Thursday, without a reserve price. Since the news broke, the frothiest conversation in the art industry has concerned what this development means, and how much it will matter in determining whether the painting meets or exceeds its estimate “in the region of $80 million”—which would make Hockney the most expensive artist alive.

For the uninitiated, the reserve price is a floor set to protect whichever party assumes the risk in an auction consignment. If bidding in the room never reaches the reserve price, the work in question goes back to either the consignor or the auction house.

If the house agrees to pay the consignor a guaranteed price for a work in advance of the auction, then the house sets the reserve and assumes ownership of the piece if bidding submarines beneath it. In the absence of a guarantee, the consignor sets the reserve and retains ownership if bidding disappoints. In either case, the reserve price never exceeds the low estimate, and most often, it is calculated as a percentage of the low estimate.

How unusual is it for a piece estimated closer to $100 million than $1 million to mount the auction block without a guarantee or a reserve? Like getting a useful cold call from a telemarketer, it just doesn’t happen. (Baer described the no-reserve strategy as “an innovative, never before used method for a top lot.”) Apart from the reserve question, even offering such a piece without a guarantee is a vanishingly rare practice in our New Gilded Age.

Yet according to Christie’s, Portrait of an Artist—which only needs to surpass the $58.4 million paid in 2013 for a work by the current most expensive living artist, Jeff Koons, to give Hockney the title—will go under the hammer with neither financial device covering it. Allegedly, the work is as naked as the baby on the cover of Nirvana’s Nevermind.

Still, the seemingly extraordinary arrangement around what everyone agrees is an extraordinary painting begs multiple questions that radiate inside and outside the art market. So let me try to address them based on my weekend of reporting.

At left, David Hockney, courtesy of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artimage. Right: Photo by Hannelore Foerster/Getty Images.

IS THE PAINTING REALLY “NAKED”?

A spokesperson’s statement on the issue is: “Christie’s can confirm that the work will be offered without guarantee and now without reserve.”

Loïc Gouzer, Christie’s co-head of post-war and contemporary art, also gave the following quote to Baer: “The consignor turned down substantial third party irrevocable bids we brought him, so it’s not a matter of no interest, it’s a matter of the market finding its real level.”

For anyone without their auction-terms cheat sheet handy, a third-party irrevocable bid is effectively a pre-sale guarantee secured from a bidder outside of Christie’s in exchange for financial incentives—often a fee from the house if the guarantor actually wins the lot, and a percentage of the upside above the guaranteed amount if they don’t.

If we take Gouzer at his word, then, Portrait of an Artist comes without a third-party guarantee. And if we take at face value Christie’s refusal to publicly acknowledge a traditional guarantee, then the work has no financial backing from inside the house, either.

Now, there have long been rumors that Christie’s status as a privately held company empowers the house to construct creative financial arrangements that skirt classification as either a traditional in-house guarantee or a third-party irrevocable bid. These rumors have never been publicly substantiated to my knowledge, but like ghost stories about an abandoned house on an overgrown hill, they linger because it’s hard to dismiss the underlying logic.

So I inquired with a Christie’s spokesperson to ask if it would be “accurate to say that no financial promises of any kind, including nontraditional risk-sharing or risk-mitigating arrangements, have been made for the painting at this time.” And after, I expect, wondering what kind of malfunctioning sub-human would write such a legalistic email at 3 a.m. on a weekend, they wrote back that “there is no form of guarantee or reserve on this painting.” Although I know smart people who believe that can’t possibly be the case, I can’t credibly prove otherwise through the digging permissible by this deadline.

David Hockney’s Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica (1990). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

BUT WOULDN’T THIS DEAL TOTALLY DEFY PRECEDENT?

By and large, yes. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.

One of the only things I’ve ever heard unanimous art-world agreement on is the notion that Portrait of an Artist is indeed the greatest Hockney painting ever. At the same time, Hockney has no directly comparable auction results. His artist record currently stands at $28.4 million for a 1990 painting sold at Sotheby’s New York this past May. Going into that sale, his all-time auction high was just $11.7 million for his 2006 painting Woldgate Woods 24, 25, AND 26 October 2006, sold in 2016. So no one really has any easy answers as to where Portrait of an Artist will land on the price index.

Now, it has been reported for months—Katya Kazakina of Bloomberg had it first—that the painting is being consigned by billionaire currency trader Joe Lewis. From the beginning, Kazakina relayed that Lewis was “seeking at least $80 million for the work.” And while the house has never, to my knowledge, actually published that number anywhere—we just get the “estimate upon request” tag instead—I was in the room a week ago when a Christie’s specialist vocalized “in the region of $80 million” at the press preview. The same figure has magically floated into every piece written about the painting by everyone else for the past three months. It’s no accident that it hasn’t been corrected.

One simple hypothesis I came out of this weekend feeling very confident about is this: Joe Lewis still feels very strongly that Portrait of an Artist is worth at least $80 million—so much so that I don’t think anyone can move him below that number. The follow-up question is how much of a risk he’s taking by digging in his heels, if that’s indeed what’s happening.

Lewis has a reputation in the trade as A) a collector who buys and sells frequently, B) a notoriously hard bargainer, and C) someone who doesn’t bring a major work to auction without some kind of financial promise. Those last two attributes can certainly work in concert—and often have, I’m told.

But they could also conflict with one another. Think about it this way: If you’ve become a billionaire based on your judgments about how much assets are actually worth, and you’re convinced to your bone marrow that this particular painting at this particular time is worth at least $80 million, why would you dilute your upside by accepting a guarantee even one dollar less? (After asking plugged-in people around the industry about the painting’s likely market value, I’ve gotten back enough answers between $60 million and $80 million to feel comfortable speculating that Lewis could have gotten a guarantee in striking distance of $70 million from a serious competitor if he’d wanted it.)

Is it the decision I would make? Probably not. But one of the only lessons I retained from calculus is that, no matter how many examples seem to verify a theorem, it only takes one counter-example to detonate the whole proof.

Joe Lewis is an octogenarian British billionaire that I have never met. I have no idea how he thinks in a game-theory situation like this. But I do know that, even if he has a long track record of negotiating major guarantees on all his consignments, willfulness can work both ways under the right circumstances. The same quality that could drive him to wrestle auction houses into promising him a price he considers right could also drive him to walk away from a price he considers wrong, no matter how many other people might accept that price gladly.

If you asked me today for one of the core truths that makes the art market so unique, I’d tell you that it’s about the chaos that can result from really big prices looming over really small numbers of players. Whether Portrait of an Artist is worth less than, more than, or exactly $80 million will be decided by fewer than 10 people, most of them acting largely independent of one another.

For instance, Joe Lewis doesn’t need to convince a board of trustees to refuse, say, a guarantee of $60 or $70 million for the prospect of hitting $80 million. Ultimately, he gets to make that call himself. And now, we’re leaning into the biggest auction week left in 2018, in which an estimated $1.8 billion in prized works could trade hands, talking about this one guy and his one painting.

David Hockney, Sprungbrett mit Schatten (Paper Pool 14) (1978). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

SO WHY ARE WE TALKING ABOUT IT, THEN?

Well, on the surface, removing the reserve is so unusual that people in the industry can’t resist gossiping. Ultimately, we’re worse than a cafeteria full of teenagers at the start of prom season. And for what it’s worth, I’m skeptical that removing the reserve will actually do much to drive up the price beyond $80 million, let alone to the $100 million that the Baer Faxt introduced into the conversation for the first time—and least of all for the reason alluded to at the end of the Christie’s spokesperson’s aforementioned statement:

By removing the reserve we have also removed any perceived barrier to entry and opened up bidding to broader participation including institutions and major donors as well as private collectors.

This democratization certainly sounds like a nice idea. But with all due respect to Christie’s, it smells funkier to me than a hot truckful of kimchi.

Based on behavioral psychology, the hope is basically this: If you can get more bidders to enter the game at the lower levels (where they think they might be able to get a deal), the spirit of competition might carry them away to a price point their rational brains wouldn’t allow them to reach in a dispassionate environment. This is why biddings wars are a thing.

But public institutions have acquisition budgets. No game-theory formulation will allow, say, the Museum of Modern Art to blow $80 million on one Hockney when its buying cap for the entire year is probably no higher than $45 million. And you’re certainly not going to see, like, the Sarasota Museum of Art nab the world’s best Hockney for $1.5 million because the work went up without a reserve.

The only institutions that will be able to afford this piece are the ones backed by billionaire private collectors, which, in my view, neutralizes the idea that institutions per se are in the mix at all.

I’m also not naïve enough to suggest that billionaires are always models of budgeting restraint. But on the whole, you tend not to become rich enough to spend $100 million on a painting by being undisciplined enough to accidentally spend $100 million on a painting. So personally, I don’t think removing the reserve is especially likely to lead to a big win, and it could backfire by animating the perception that interest has been soft enough to warrant late-stage gimmickry.

But again, the point here is that probability is a dangerous game to play in the thin air at the art market’s peak. Nobody without inside knowledge would have bet that the Salvator Mundi would sell for anything remotely close to $450 million at Christie’s New York last year, and nobody without inside knowledge would have bet that a Banksy painting would become more valuable by shredding itself in its frame at Sotheby’s London last month.

Yet both those things happened. More than great works and good business, these events, these cliffhangers, are what premier auctions are about now. What makes sense matters far less than what makes headlines. As the madness unfurls over the next week with Portrait of an Artist and who knows what else, even the setups can make us feel like anything is possible again. And on a dying planet in sociopolitical chaos, that sense of possibility may be what most of us want most of all.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, wish me luck with hammer time.