Photo: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, via Smithsonianmag.com

In his article titled “Lauder Editorial on Stolen Art and Museums Fails the Glass House Test,” Nicholas O’Donnell attempts to respond to Ronald S. Lauder’s editorial published in the Wall Street Journal on June 30, 2014, titled “Time to Evict Nazi-Looted Art From Museums.”

O’Donnell attempts to find legal shortcomings in Lauder’s editorial, which simply expresses the need for art museums to act responsibly by returning Nazi-looted artwork instead of raising technical defenses and mere pretexts to deny the rights of the claimants.

In his article, O’Donnell refers to the ongoing case brought by Léone Meyer against the University of Oklahoma, among other defendants, to obtain the restitution of La bergère rentrant des moutons (Shepherdess Bringing in Sheep) (Camille Pissarro, 1886), currently on permanent display at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman, Oklahoma.

Although O’Donnell—counsel to David Findlay, Jr. Gallery, a defendant no longer involved in the case—recognizes that the recent court decision is limited to whether the Oklahoma defendants could be sued in New York, he repeatedly brings up a 1953 Swiss court decision involving Camille Pissarro’s La Bergère as grounds for why Léone Meyer’s claim should fail, and why Mr. Lauder’s argument is baseless.

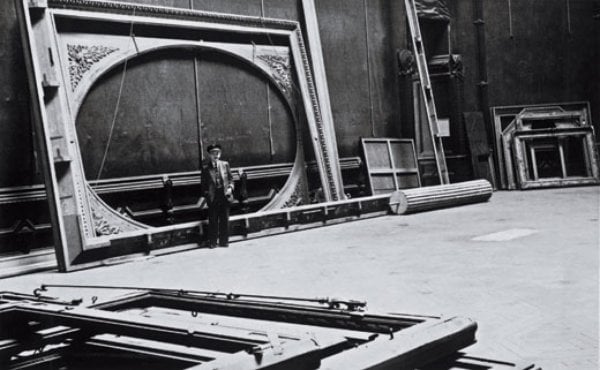

Looted material waiting to be sorted.

Photo: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD via Smithsonianmag.com

O’Donnell’s argument fails the common sense test. First, no one disputes that the Nazis stole La Bergère from Léone Meyer’s family.

Second, the 1953 Swiss court decision was not decided based on a late claim, as O’Donnell argues, but was decided against Léone Meyer’s father because he could not prove the “bad faith” of the art dealer who acquired La Bergère after it crossed the Swiss border from France.

Third, prior Swiss decisions involving looted art have long been held as doubtful or baseless in several US jurisdictions. Even the Swiss government itself recognized in 1998 that the deck was stacked against claimants who wanted to file art restitution claims in Switzerland after World War II. New York courts have determined that “Swiss law places significant hurdles to the recovery of stolen art, and almost ‘insurmountable’ obstacles to the recovery of artwork stolen by the Nazis from Jews and others during World War II and the years preceding it.”¹

Finally, O’Donnell misses the point of Mr. Lauder’s editorial. As French government officials have recently stated in a public forum dedicated to France’s efforts to track and restitute looted art, the time for “clean museums” has come. Hiding behind technicalities and procedural loopholes to delay basic justice, i.e., restitution of looted property, is not morally appropriate, even less so when public institutions are involved.

Ronald Lauder is right. It is time for museums to do the responsible thing. It is time for museums to “clean” their collections of any tainted artwork by returning Nazi-looted artwork.

1 Bakalar v. Vavra , 619 F.3d 136, 140 (2d Cir. 2010); see also In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation, 105 F. Supp. 2d 139, 159 (E.D.N.Y. 2000)

2 “Bilan des actions publiques en France et perspectives suite aux conclusions de la mission parlementaire sur les œuvres d’art spoliées par les nazis,” Colloque organisé par Corinne Bouchoux, membre de la Commission de la Culture, de l’Éducation et de la Communication du Sénat et Sénatrice de Maine-et-Loire, Palais du Luxembourg, Salle Monnerville, 30 Janvier 2014.

Pierre Ciric is a New York attorney, the founder of the Ciric Law Firm, PLLC, and a board member of both the French–American Bar Association and the New York Law School Alumni Association. He currently represents Léone Meyer against the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma in her quest to obtain the restitution of La bergère rentrant des moutons (Camille Pissarro, 1886), currently on permanent display at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman, Oklahoma.