Today, Surrealism is thought of as being synonymous with artists like Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst, or Man Ray. Over the years, names of women artists like Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, and Leonora Carrington have garnered increasing recognition for their pivotal role in the movement’s evolvement; but these are just a small fraction of the women Surrealists that have historically helped pioneer Surrealism’s evolution and trajectory from the early 20th century through today.

In any case, no movement or style has captured imaginations worldwide quite like Surrealism; simply uttering the word Surrealism conjures images of dreamlike and uncanny worlds and mind-bending vignettes. A vast range of exhibitions and events staged this year to mark 100 years since the movement’s inception are a testament to its enduring influence and legacy.

Yayoi Kusama exhibition at 3 Venues, in Paris. (Photo by Alain Nogues/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images)

At the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, a recently opened “Long Live Surrealism! 1924–Today,” which traces the movement’s evolution throughout the 20th century and its continuing relevance today, showing works from Ernst and Carrington as well as those they inspired, like Yayoi Kusama. At the Centre Pompidou, the show “Surréalisme” presents a sweeping chronological, thematic, and cross-disciplinary look at the origins of the movement as proposed by André Breton. The Royal Museums of Fine Arts Belgium in Brussels; the Museum of Art Pudong, Shanghai; and the Heide Museum, Melbourne, all have or had exhibitions centered on the seminal movement.

Earlier this month at New York’s Independent 20th Century, Surrealism was a recurring theme identifiable throughout the fair, from Galerie Michael Janssen and Marisa Newman Projects showcasing the work of Susana Wald, who has explored Surrealism from a feminist standpoint throughout her more than 60-year career, to Richard Saltoun presenting “Butterfly Time: A Group Exhibition of Women in Surrealism,” part of a three-part series continued in the gallery.

This flurry of programming has shone a light on overlooked female pioneers who are now being re-appraised and given their moment to shine, as well as inspiring a new generation of women artists pushing the genre to new heights.

The surrealist painter Salvador Dali works on the figure of two birds in Greenwich Village, New York. Photo: © Bradley Smith/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

But First: What Is Surrealism?

Surrealism is widely traced to 1924 with the publication of the Surrealist Manifesto by French poet and art critic André Breton. The term “Surrealist” was first introduced in 1917 by French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, and was later influenced by psychology, Sigmund Freud, and Dadaism. Tapping into the subconscious mind and dreams, Surrealist art pays no mind to convention and expectation but instead proposes new perspectives and unbridled expression or “psychic automatism,” wherein conscious thought takes a backseat.

The 1920s, however, was in many ways the golden age of manifestos, and Breton’s was not the only one. Two weeks before Breton published his work, the French–German poet and Breton rival Yvan Goll produced his own Surrealist manifesto. Both writers were based in Paris and deeply involved with respective groups of artists who engaged with the philosophical and aesthetic tenets of the movement. From this moment forward, Surrealism spread across the world like wildfire, influencing not just visual art but literature, film, music, even social and political thought across borders and languages.

Kay Sage, I Walk Without Echo (1940). Sotheby’s Modern Evening Sale, 2022.

The Overlooked Pioneers

The groups of artists that followed Breton and Goll respectively in the 1920s were overwhelmingly male, but nevertheless numerous women artists both in Paris as well as internationally adopted the precepts of the movement and produced powerful bodies of work that furthered Surrealism on the whole. Kay Sage (1898–1963) was one such artist.

Sage was an American painter whose unique approach to Surrealism is recognized for its elements of architecture, rich color palette, and lithe lines, resulting in what art historian Whitney Chadwick described as “an aura of purified form and a sense of motionlessness and impending doom found nowhere else in Surrealism.” Originally from Albany, New York, she moved to Paris in 1937, where she participated in the International Surrealist Exhibit and Salon des Surindépendants, both in 1938. It was also in Paris where she met fellow Surrealist Yves Tanguy, whom she later married.

Though Sage’s work and practice suffered from a lack of critical attention, in recent years there has been a marked increase in interest. In 2022, her work I Walk Without Echo broke the million-dollar mark in the Sotheby’s New York Modern Evening Sale. And this June, her solemn The Other Side of the Square sold for $635,593 at Piasa in France, well above its $150,000 estimate.

Gertrude Abercrombie, Search for Rest (Nile River) (1951). Collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra. Photo: Sandy and Bram Dijkstra. Courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Another early 20th-century Surrealist long under-appreciated and undergoing a much-deserved reappraisal is American artist Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–1977). Born in Austin, Texas, Abercrombie spent much of her career based in Chicago, where she earned the title “queen of the bohemian artists” as she regularly organized gatherings at her home that brought together avant-garde artists from her circle.

Abercrombie’s compositions frequently depict vacant landscapes, interiors with barely any furnishings, or sparse still lifes, and the figure of a woman in flowing dress frequently crops up across her oeuvre. Although well known locally, she never achieved commercial gallery representation, and her legacy faltered after her death. The artist’s life and work, however, are in the midst of a revival as she is the subject of an institutional solo with “The Whole World is a Mystery,” which goes on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, January 18–June 1, 2025, bringing her contributions to the movement to a new and wider audience.

Sarah Schumann, Untitled Shock Collage (1967). Courtesy of Diane Rosenstein Gallery, Los Angeles, and Van Ham Art Estate, Cologne.

Women Artists Evolving the Style

While focus is often drawn to the early years of the movement, Surrealism’s ability to be adapted and personalized is what has ultimately made it the iconic style it is recognized as today. And the evolution of Surrealism throughout the later decades of the 20th century can be attributed to the practice and work of women Surrealists.

Sarah Schumann (1933–2019) was born in Berlin and helped pioneer and transition the trajectory of Surrealism within the context of postwar Modernism. Incorporating themes of feminism—largely inspired by her own life and queer identity—as well as Schrecken und Schönheit, or “horror and beauty,” Schumann’s oeuvre speaks to both the deeply personal yet widely relatable lived experiences as a woman and an artist.

Sarah Schumann, Konvexspiegelung über dem Meer und dem Tod in den Alpen

(Convex Reflection Over the Sea and Death in the Alps) (1982). Courtesy Diane Rosenstein Gallery, Los Angeles and Van Ham Art Estate, Cologne.

Schumann contributed to not only dialogues around the continuing development and expanding definition of Surrealism, which in many ways can be understood as a bridge from early to contemporary Surrealism, but also of feminist artmaking and the recognition of women artists at large. Self-described as “a courageous, strong, combative artist,” in the 1970s Schumann was member of the feminist artist collective Brot + Rosen (Bread + Roses), and she curated the groundbreaking survey “Women Artists International 1877–1977” in Berlin. This specific show illuminates a facet of Schumann’s approach to art, as it was comprised of only women artists and sought to foreground their historic and ongoing engagement with feminism within the context of a male-dominated art world.

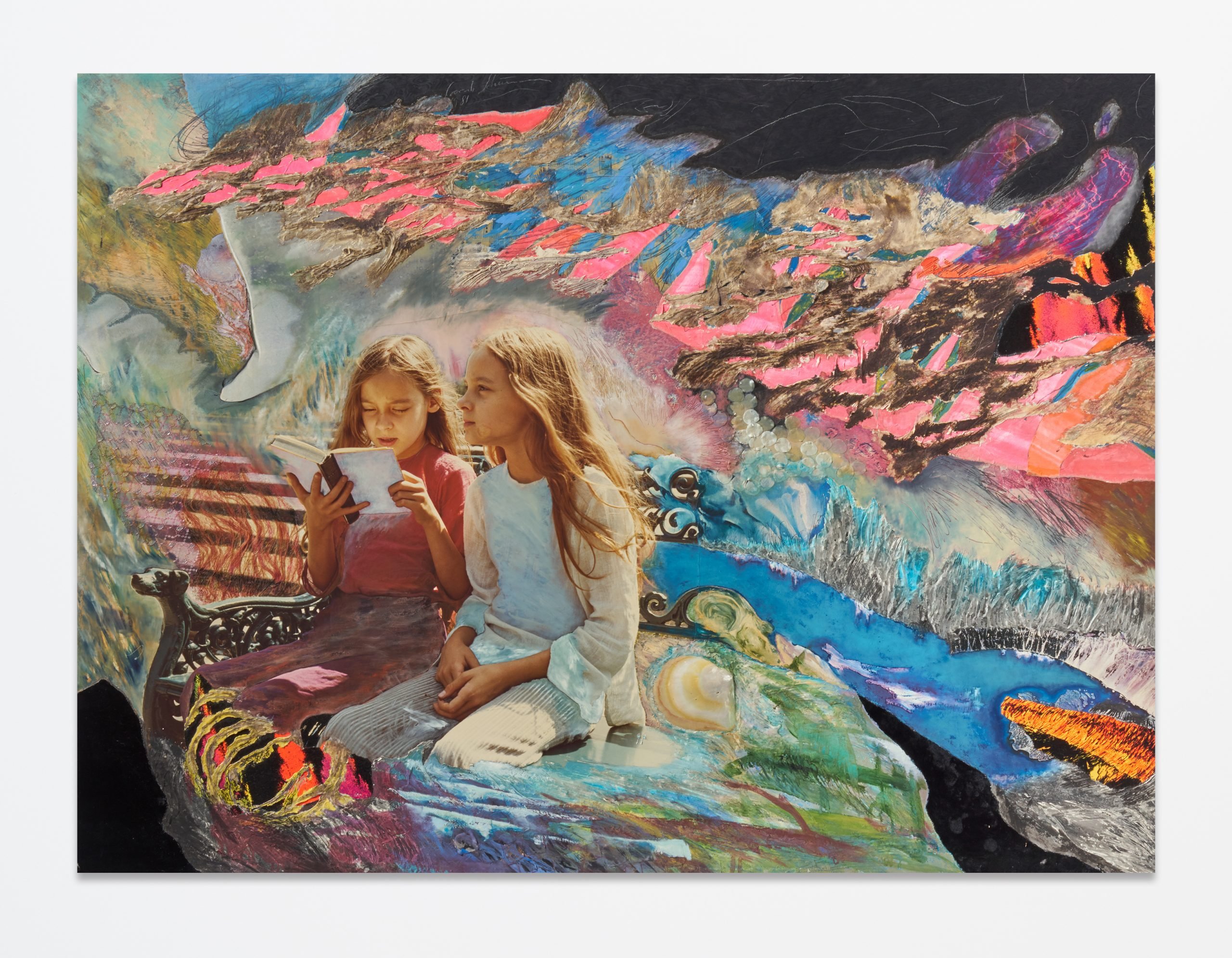

A collagist as well as painter, some of Schumann’s earliest works were a series of “Shock Collages,” made between 1959 and 1967, black-and-white compositions made of layered images drawn from books and magazines that she then photographed. While these early works reflect more traditional modes of artmaking, her later work, specifically from the 1980s, showcases a profound progression in her creative vision. Overflowing with color and motifs, these works bring together images of people and places from her personal life as well as abstracted elements that evoke ideas around memory, nostalgia, and feminism.

Inka Essenhigh, Rave Scene (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Miles Mcenery Gallery, New York.

Contemporary Practitioners

The Surrealist tradition today continues to be a potent source of inspiration, and a range of women artists are continuing to make it their own, following the legacies of Schumann, Abercrombie, and Sage. These contemporary artists are part of the ongoing reinvention of Surrealism, and present viewers with an opportunity to consider what might come next, as the style, ideology, and techniques of the movement are brought into the 21st century.

New York-based artist Inka Essenhigh (b. 1969) employs a characteristic element of narrative in her compositions, which is heightened by her dexterous ability to manipulate renderings of space and a vacillation between representational and abstracted form. Referencing themes related to mythology, psychology, and dichotomies such as urban versus rural, Essenhigh’s paintings offer glimpses into imaginative worlds that appear just outside of reality, presenting new avenues of Surrealist exploration. Her work’s place within contemporary Surrealism was explored in the recent Phaidon publication New Surrealism: The Uncanny in Contemporary Painting by Robert Zeller, and in 2025 she will be the subject of a solo show at Victoria Miro, London.

Emily Mae Smith, Offering (2024). Photo: Charles Benton. Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

Like Essenhigh, Emily Mae Smith (b. 1979) also taps mythology in her practice as well as art history, including movements such as Art Nouveau, Symbolism, and Surrealism. In Smith’s work, however, Surrealism is leveraged not simply as a stylistic approach but a psychological, even political one. Incorporating wry humor and playful vignettes, anthropomorphized objects like brooms and hyper-stylized accessories result in a type of surreal world-building. Not only is her work currently included in the Blanton’s “Long Live Surrealism! 1924–Today,” but she is also slated to have a solo show at the Magritte Museum, Brussels, where her work will be in dialogue with that of the preeminent Surrealist.

Julie Curtiss, States of Mind (2021). Photo: Charles Benton. Courtesy of the artist and White Cube.

And in artist Julie Curtiss’ practice, contemporary lived reality is accentuated through the addition of uncanny details—flamingos and an alligator lounge in a pristine living room, or the reflection of a handheld mirror is a skull looking back at the viewer. And outside of the graphic, Curtiss uses tondo or other shaped canvases to blur the line between reality and perception. Surrealism takes on a decidedly contemporary slant, as themes of technology, modern communication, and real versus perceived reality lay just beneath the surface.

Julie Curtiss, Tropical Dawn (2023). Photo: Charles Benton. Courtesy of the artist and White Cube.

Tracing this thread through time—from the earliest pioneers of the Surrealist movement who were often overlooked and dismissed, down through generations of women painters that are experiencing wide success—shows that the movement and its feminist roots are captivating news audiences, and offers insight into the how Surrealism can continue to evolve into the future.