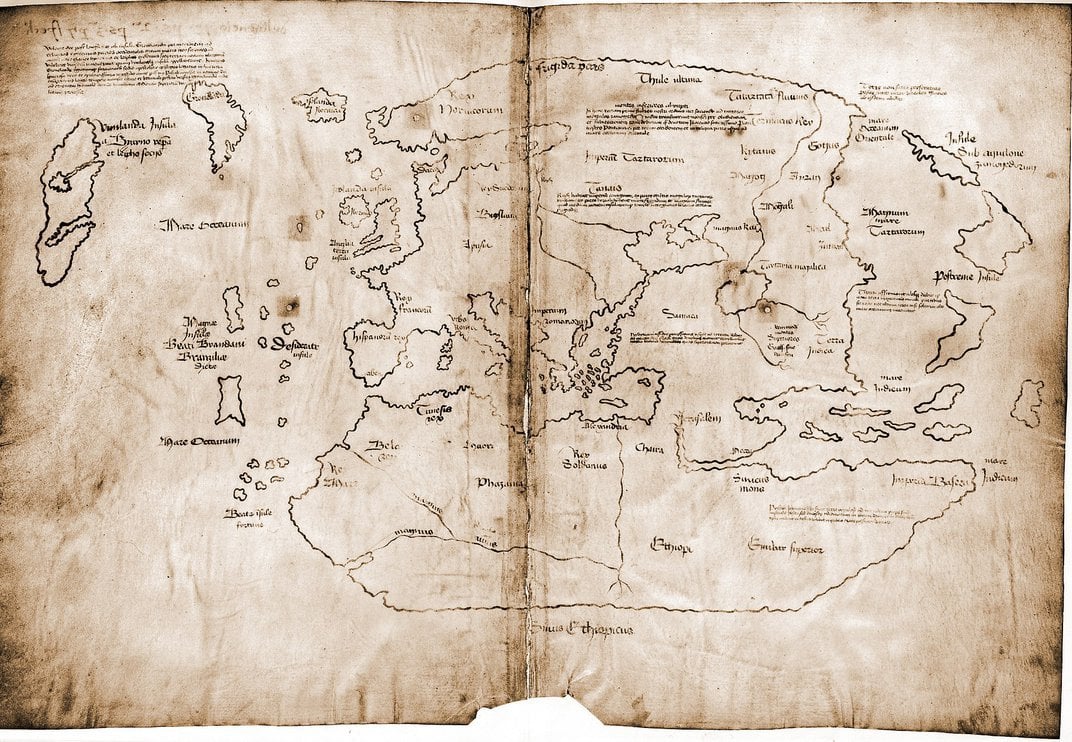

The Vinland Map, once believed to be the earliest cartographic depiction of the New World, has been proven to be a modern forgery, confirming long-held suspicions. A team of conservators and scientists at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, conducted an in-depth analysis of the purported 15th-century map, determining that it was drawn with 20th-century inks.

“The Vinland Map is a fake,” Raymond Clemens, curator of early books and manuscripts at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, said in a statement. “There is no reasonable doubt here. This new analysis should put the matter to rest.”

Yale acquired the parchment map for the library as a gift from Paul Mellon in mid-1960s and unveiled it to great fanfare in 1965, publishing a scholarly book on this view of the North American coastline southwest of Greenland, labeled as “Vinlanda Insula.” Making the front page of the New York Times, it was hailed as support for archaeological evidence that the Vikings had visited North America long before Christopher Columbus.

But questions surrounding its authenticity arose almost from the start. The map lacks the ornamentation typical of medieval cartography. It’s also quite accurate in its geography, depicting Greenland as an island, .

Yale University’s Vinland Map, thought to be the earliest depiction of North America, is now proven to be a modern fake. Collection of Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

The British Museum in London had previously declined to purchase the map. Dealer Laurence C. Witten II, who sold the work to Mellon, wouldn’t say how he had gotten the manuscript, and had links to known manuscript thief Ferrajoli de Ry, reports Smithsonian Magazine. He later admitted to buying the map from De Ry without asking for provenance information.

In 1973, the McCrone Research Institute in Chicago uncovered the first evidence that the map was not what it seemed when tests found traces of anatase, a form of titanium dioxide that was first used in commercial inks in the 1920s. Conflicting reports followed in the subsequent decades, leaving a cloud doubt surrounding the document’s veracity.

Armed with state-of-the-art tools and newly developed techniques, Yale Library’s Center for Preservation and Conservation and the university’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage set out to get to the truth once and for all, carrying out a full battery of tests to identify the map’s elemental composition.

Macro X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) revealed the presence of titanium throughout the Vinland Map’s lines and text. Photo courtesy of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

For the first time, they used X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), a non-destructive technique, to scan the entire map, not just studying specific areas. The titanium was found to pervade the entire map, and the ink contained little to no iron, sulfur, or copper—the elements that make up the iron gall ink typically used by medieval scribes.

The scientists compared those readings to tests done on 15th-century manuscripts from Central Europe in the library’s collection, and found that the Vinland Map has much higher levels of titanium and much lower levels of iron.

The same was true with the Speculum Historiale and the Hystoria Tartorum, or Tartar Relation, the two authentic medieval manuscripts linked to the Vinland Map—an especially telling result, and the first time the three had been examined side by side with field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM).

An X-ray fluorescence spectrometer scans the Vinland Map to create elemental maps revealing the distribution of elements throughout the parchment. Photo courtesy of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

All in all, the map’s anachronistic anatase was a close match to ink produced in Norway in 1923, making it unlikely that the compound had somehow occurred naturally.

When Yale acquired the Vinland Map, it was within a copy of the Tartar Relation, a 1247 travelogue written by Polish missionaries to the Mongol Empire, but with a modern binding. The only other known copy of the Tartar Relation, recently discovered in Lucerne, was bound with the Speculum Historiale, a four-volume medieval encyclopedia by Vincent de Beauvais. And the wormholes in the Vinland Map matched those in a copy of Speculum Historiale that Yale acquired not long after, suggesting that all three were once bound together.

Infrared light exposed altered text in the Tartar Relation, the authentic medieval manuscript that the map was bound with when it arrived at Yale. Analysis showed the altered text is composed of modern ink. Photo courtesy of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Experts now suspect the Vinland Map was drawn on calfskin parchment from the end sheets of Yale’s Speculum Historiale. The forger appears to have altered a Latin inscription on the back of the parchment with modern ink, to make it seem like a medieval bookbinder had left instructions for integrating the map into the larger volume.

“Whoever did it must have been a really skilled calligrapher,” Dale Kedwards, a map historian at Iceland’s Arni Magnusson Institute, told the New York Times, noting the map had fooled “some wonderful scholars.”

But even though the Vinland Map is fake, Yale plans to keep it.

“The map has become an historical object in and of itself. It’s a great example of a forgery that had an international impact,” Clemens said. But, he added, he hopes that experts can focus further research on authentic works. “Objects like the Vinland Map soak up a lot of intellectual airspace. We don’t want this to continue to be a controversy. There are so many fun and fascinating things that we ought to be examining that can actually tell us something about exploration and travel in the medieval world.”