Zineb Sedira’s experience living between cultures—in Algeria where her parents are from, in France where she grew up, and in England where she has lived and worked since 1986—has always informed her work.

Sedira makes films that blend autobiography, fiction, and documentary to invoke broader questions about individual and collective memories and identity, which have often honed in on the connecting and dividing lines between Europe and Africa.

Significantly, she is first artist of Algerian descent selected to represent France at the Venice Biennale, and her presentation takes its jumping off point from the numerous postwar cooperation projects between France, Italy, and Algeria. These projects aimed to promote cultural exchange, and many were underwritten by Algeria in an effort to break away from French colonial representations and build its own culture and image.

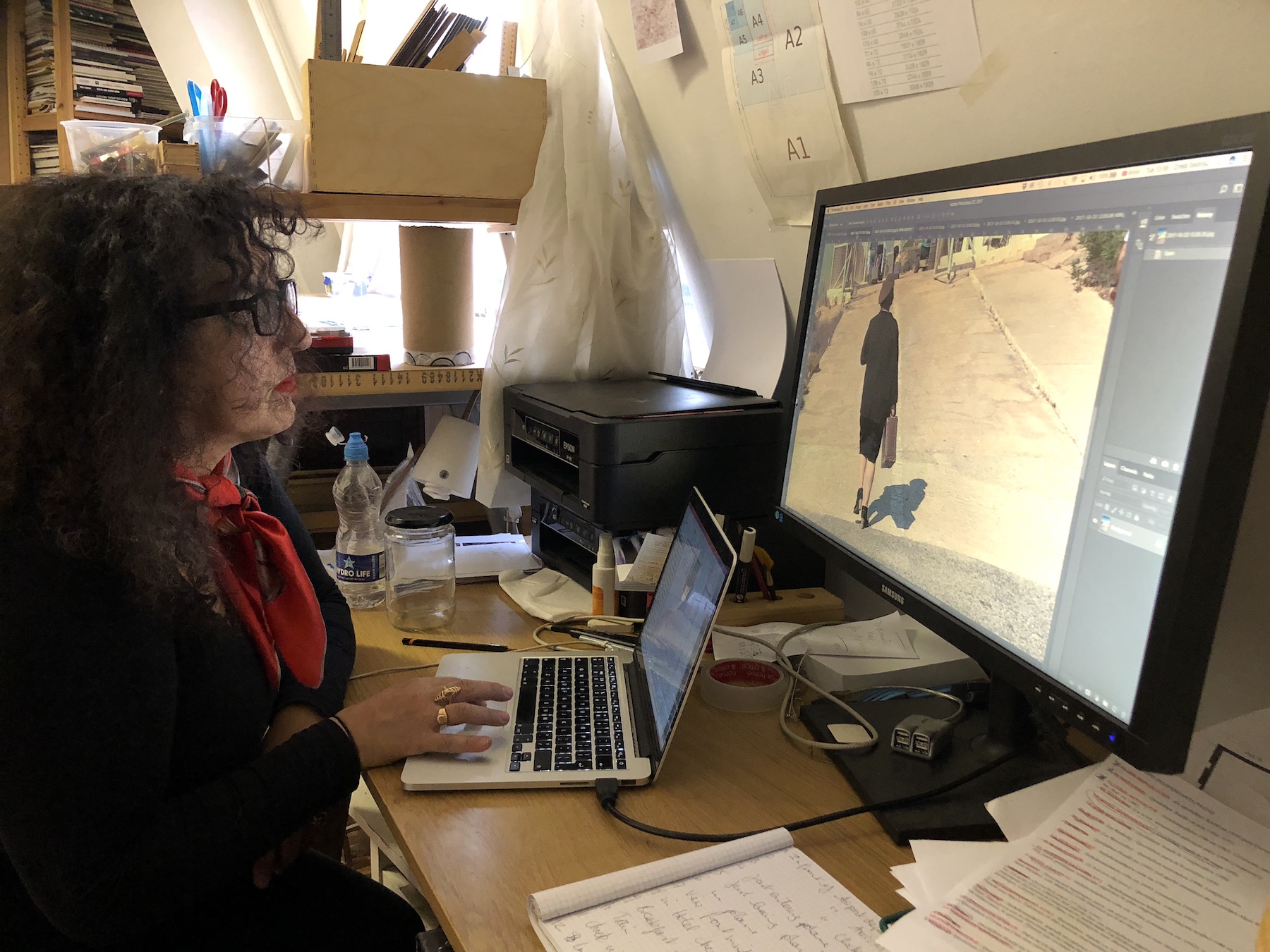

We caught up with the artist in her London studio where she was preparing to head to Venice. At the biennale, she has transformed the French pavilion into a cinematographic installation in which to watch her film Les rêves n’ont pas de titre/Dreams have no title.

Messy studio. Courtesy Zineb Sedira.

What is the most indispensable item(s) in your studio, and why can’t you live without it?

I would tend to say it is my computer but other than that, probably scissors and glue, I think, because I’m always cutting and sticking stuff.

The most indispensable item in the studio. Courtesy Zineb Sedira.

What is the studio task on your agenda this week that you are most looking forward to?

Reorganizing and preparing for when I come back from Venice, because the studio is a mess. At the moment I’m just trying to clear up the studio a bit and make it more welcoming for when I come back. This is my main task.

Messy studio. Courtesy Zineb Sedira.

Can you send us a picture from your last site visit to Venice? What was the main to-do of that trip?

We visited in January and I shot my film there. Not all of it, but around 90 percent of it. It was a bit difficult, but we had to do it because of the content of the film—it has to be in Venice, so we had no choice. It was very cold, and because of the COVID restrictions, it wasn’t easy. We had to wear masks all the time and it was tough to shoot, especially in 60mm film, wearing masks.

People who were acting didn’t have to wear a mask obviously, but the crew did. There are quite a few “making ofs” where you see the crew filming this way. In some ways it sets it into the right timeframe, during the COVID time, so that’s not a bad thing, but in terms of the practicalities it was tough because you’re having to spend all your time in a mask.

Site visit to Venice. Courtesy Zineb Sedira.

What has been the biggest challenge so far, as you prepare for the Venice Biennale?

The biggest challenge was not being able to travel because my project is very much research based, especially in archives. It was very tough to not be able to travel, and we had to cancel a few trips at the last minute because the rules were changing all the time.

So the toughest part was to not be able to easily access—I did in the end, but not easily—these archives. And also to not be able to go to Algeria because Algeria was really in the red zone and you could not travel there. I didn’t go to Algeria during the whole period of my research, and that was quite tough because it has an important part in the project.

Many archives [digitize their materials], and so it was kind of manageable for five months, but this isn’t the case in Algeria. Things haven’t been digitized. I did find ways around it, where I got people locally to go and do some research for me. Because the archives were open over there, but it was the traveling there that was difficult. So I hired a local person, a consultant, to do the research locally for me.

Is there a picture you can send of your work in progress?

Work in progress. Courtesy Zineb Sedira.

We are getting toward the end now. We are almost done, but there are a few things left to finalize: the grading and the sound mix and things like that.

My editor and my sound technician send me a version of the editing every evening, and every evening, religiously, I sit in front of it with a very good speaker and listen and watch it through. Then I give my comments to them, and the following day they send me another edit.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

Usually I go out and walk, or go and do a bit of shopping—I get out of the studio. I just try to change my mind and go somewhere else.

What trait do you most admire in a work of art? What trait do you most despise?

The trait I like the most is when forms and content connect very well. So when aesthetics and politics—because I tend to like work which is more political—work well together.

I don’t think I despise anything to be honest. I think I respect every type of art making. I might not understand some of it, I might not engage with some of it, but I wouldn’t go as far as to say I despise it.

What are you looking at while you work? Share your view from behind the canvas or computer, wherever you spend the most time.

Messy studio. Courtesy Zineb Sedira.

I spend a lot of time at the computer, and I’m looking at my work. I’ve got tons of books and I’ve got some videos because my project is about films. So I’m looking at those things, I’m reading a hell of a lot of books and reading online. And I have been watching a lot of films for this project. I’ve watched tons of films.

What is one film, piece of writing, or other artwork that inspired you most in preparing for Venice?

There’s an Algerian film that’s not known well at all called Les Mains libres in French. I weaved my whole project around this film. It’s a film from 1964 that was lost for many, many years, and that I found in Italy in one of the archives. I think it’s a brilliant film. It’s a documentary essay. So this was extremely important—so important that I actually managed to get it fully restored with the Cineteca di Bologna in Italy, and then I weaved it into my own film.

I came across it through a lot of reading on Algerian cinema, and I could see everywhere that came out in ’65, that it was shown in Algiers and a few other places, but at the end of ’65 It stopped showing and it kind of got lost. Nobody knew where there was a copy of it. And we actually found it in Italy.

What’s your favorite hideaway to eat, drink, or to take a break in Venice?

Because we were there in January and everything was closed, I can’t think of any particular place. Obviously there is just walking by the water, and that for me is always a big pleasure.

The greatest moments were when I was in the pavilion working with my crew and my friends. Because the whole project is about friendship. We were there 10 hours a day, every day. Those moments of chatting and laughing and warmth between us, it was consuming our days, and I really enjoyed that.