The women of Abstract Expressionism are rising from obscurity in a big way. But, until this spring, one foundational West Coast figure had yet to receive her due. Through May 7, Van Doren Waxter in New York is presenting the first solo show celebrating Zoe Longfield—73 years after a toxic marriage ended her promising decade-long career.

Installation view. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

“It’s always the right time to show amazing art,” said gallery partner Liz Sadeghi. “People have been trying hard to shine a light on these forgotten artists. We have been trying to do that as well.”

Zoe Longfield, Untitled (c. 1948) Oil on canvas. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

Van Doren Waxter, which has drawn awareness to artists like Jackie Saccocio and Mariah Robertson, first learned of Longfield through a collector. While the confident radiance of Longfield’s abstract paintings stunned Sadeghi and John Van Doren, her time studying under Richard Diebenkorn, whose foundation the gallery represents, sealed the deal. Van Doren Waxter started representing Longfield’s estate last May.

Installation view. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

Born in San Francisco in 1924, Longfield earned her undergraduate degree between 1941 and 1944, learning from Berkeley School founders like Margaret Peterson and Erle Loran. Three years later, she attended San Francisco’s legendary California School of Fine Arts, where celebrated Abstract Expressionist Clyfford Still taught her the foundations of color, from which Longfield forged her own varied palette.

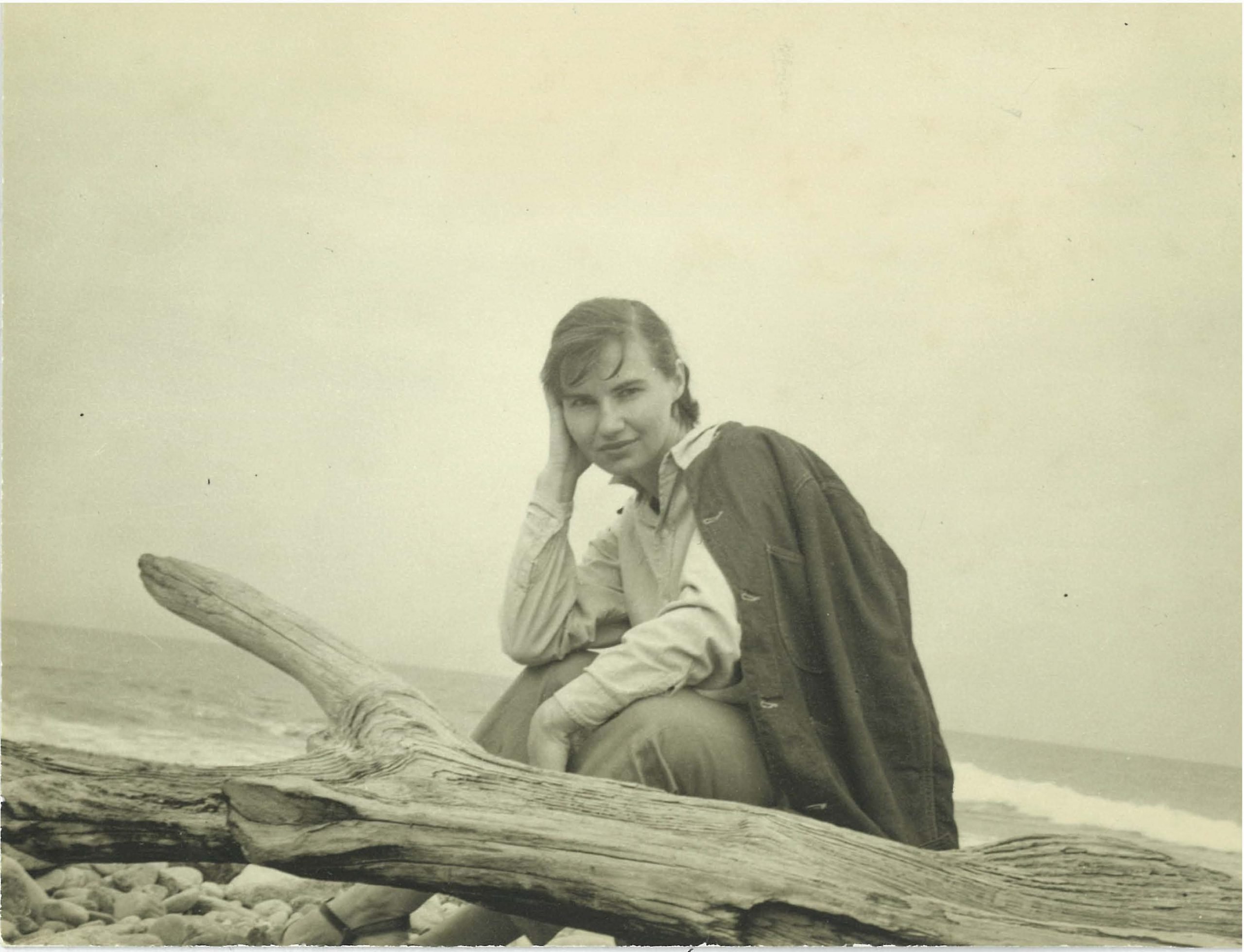

Longfield seen as the only woman in David Park’s Studio Painting Class. Photograph by William Heick, c. 1948 courtesy of San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation+Archive

Longfield became one of few women admitted into Still’s inner circle. “She was one of the very few women who was at the California School of Fine Arts in the first place,” Sadeghi noted. “She was very audacious and independent. She had her own mind and style. I think he really appreciated that.” While Longfield also excelled as a figure skater, she always came back to art. “She described wanting to solve those inherent problems peculiar to painting,” Sadeghi said.

Zoe Longfield, Untitled (c. 1949-50) Oil on canvas. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

At CSFA, Longfield also became one of just 12 students that Still tapped to form Metart Gallery, a trailblazing artist-run space in San Francisco. Longfield had studied at the Marxist California Labor School between Berkeley and CSFA. Still’s anti-commercial aims resonated with her.

Longfield’s Phelan letter from 1949. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

Longfield received acclaim from 1948 through 1951. She applied for the Phelan Award in 1949—and though she wasn’t selected, she was one of three applicants who received a letter emphasizing her work’s promise.

Hagan’s review of Longfield’s work, on view in the show. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

Metart Gallery lasted only a year. When art critic R. H. Hagan saw her solo show, he gave her a glowing mention in the San Francisco Chronicle. However, the gallery mostly launched her male cohorts, especially Ernest Briggs and Edward Dugmore. The gallery’s last show in Spring 1950 centered on Still. Longfield married Raphael Etigson the following February, then followed him to New York.

Ephemera on view. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

The marriage did not work out; Etigson cheated. Longfield divorced him and moved back to California in 1957. Despite her anti-capitalist values, she spent the rest of her life supporting herself through commercial art. “I think she was just so beaten down,” Sadeghi reflected. “She had this early, great success. Once she was taken out of it—went to New York, and then came back—she lost her mojo,” which Sadeghi later specified meant “motivation.”

Zoe Longfield, Untitled (c 1949-50) Gouache on paper. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

But, interest in Longfield renewed due to shows around the West Coast abstract expressionists at SFMoMA in 1996, and in 2004 at Sacramento’s Crocker Museum of Art—where Longfield finally got to see her art on view in an institution, nine years before her death.

Zoe Longfield, Untitled (1948) Oil on canvas. Photo: Van Doren Waxter

Van Doren Waxter presents essentially two bodies of paintings. One exemplifies Longfield’s affinity for thick paint and totemic, biophilic forms. The other highlights her silkier works, with diaphanous washes. Gouche paintings on paper offer further context, as does an arrangement of ephemera from Longfield’s life as a girl, student, and artist.

“Zoe Longfield” is on view at Van Doren Waxter, 23 East 73rd Street, New York, through April 27. A condensed iteration will on private view through May 7.