“From One Woman to Another,” a five-part series co-produced by artnet News and Mark Cross, features intimate, candid conversations between eminent women at the pinnacle of the art industry and a mentor or protégé of their choosing, paired with original photography by David Lipman.

In the third installment of the series, artnet News’s Noor Brara interviewed gallerist Mariane Ibrahim and her mentor, Marieluise Hessel, a collector, scholar, and co-founder of Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies.

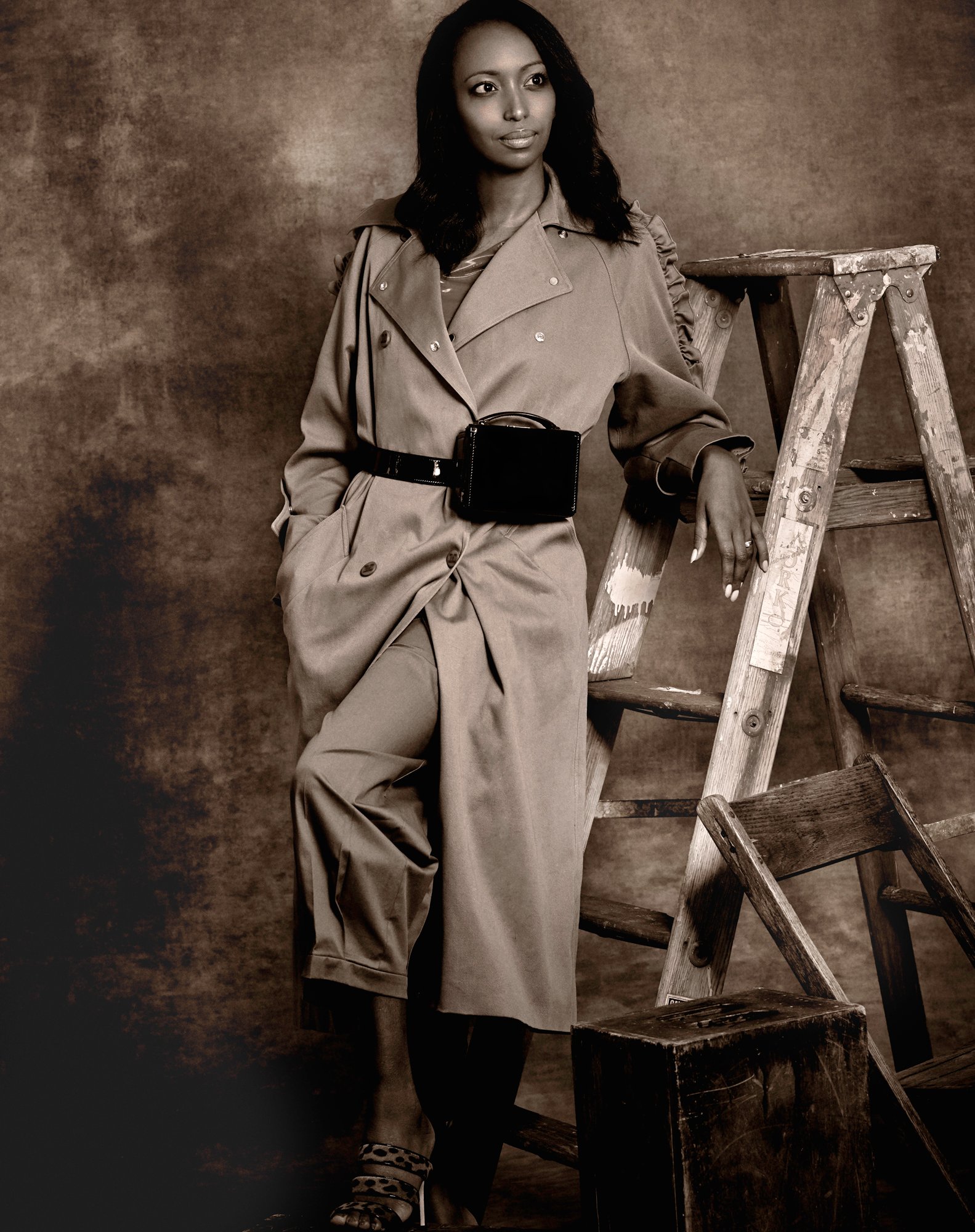

Chicago-based gallerist Mariane Ibrahim is easily one of the most-watched rising stars of her generation.

The French-Somali dealer has garnered attention for making a concerted effort to represent a roster of emerging artists—primarily those from Africa and the African diaspora—who work in particularly nuanced, sophisticated ways. With an eye to building an energetic community of like-minded artists, collectors, and dealers, Ibrahim is not shy about her ambition to be an agent for change—not only in the art world, but also in the city and country in which she resides.

In many ways, Marieluise Hessel, the German-born collector, shares the same ethos. Her collection, housed in the Hessel Museum at Bard College’s elite Center for Curatorial Studies, which she co-founded in 1992, consists of more than 2,000 artworks by international artists. Her passion for learning about these artists has bonded her to Ibrahim, beginning a relationship that they now describe as familial.

We spoke to Ibrahim and Hessel about how they connected; how they talk about representation, race, and politics in the art world; and what advice they have for young women in the art industry today.

Tell me about your backgrounds. Where did you grow up and how did you come to fall in love with art?

Mariane Ibrahim: I’m technically Polynesian—I was born in New Caledonia to Somali parents. I grew up in Europe, and now I’m living in the US, so I’m pretty transcontinental. Having a mixed background dictates and shapes one’s vision, because you keep being exposed to different places and different landscapes. It’s not just about traveling and passing through multiple places; it’s about being there long enough to absorb the culture, the language and memories.

I think art offers that endless appetite, too, to learn and to see new things. You’re constantly having to question your eye. Why does it look like this, and not like that? Why do I find this pretty, and that not pretty? At a very early age, growing up in France, a place where I was surrounded by history and beauty, I began to ask what my contribution could be.

While I enjoyed all of my experiences, living in different places was challenging, and I’ve never truly felt comfortable anywhere. I’ve never had a feeling of ease, because I may be the only Black person in that room or in that company. So given that comfort never really existed for me, I found it within myself, which gave me confidence no matter where I was.

Marieluise Hessel: I grew up in devastated postwar Germany, and there wasn’t really any art that I could fall in love with. But as a child, I spent a lot of time in a precious little Baroque church where I found peace and beauty. I also loved our school and family visits to King Ludwig’s Schloss Linderhof. It was a place where I could dream about a world that one day I would live in. I suppose that’s how I fell in love with art initially.

How did you two meet and how did your relationship begin?

Hessel: I met Mariane through my sister Christina Lockwood, who lives in Seattle, where Mariane initially had a gallery. Because of my interest in the arts, Christina thought we should meet.

Ibrahim: Immediately we connected and we stayed in touch, and I started learning about her program at Bard and going to her events. As I started doing more and more in New York, Marieluise became more present in my work and my career. I’d never really had a constant source of wisdom or support in the same way. Everyone else around me were my peers, and it was more about competition. I wasn’t working with collectors who were as experienced as Marieluise, who has been collecting over 40 years. She is an institution in herself, but also under the radar, which I really love about her. She keeps a low profile, but she’s extremely knowledgeable.

From there, we started emailing and then talking on the phone, having breakfasts and lunches. She was empathetic to the solitude that I felt working in this business. She knew many incredible dealers and gallerists and she had seen them grow to become mega-dealers and major gallerists, so I wanted to learn from her about what makes a successful art dealer. That’s how we became close.

Marieluise, your collection is in many ways the bedrock of CCS Bard. How did you come to be involved with the Hudson Valley college? And what was your objective when you first established the Hessel Museum?

Hessel: A long time ago, I realized I owned more artworks than I could live with. At that time, I thought that my collection should go to a small-town museum after my death. Then, in 1987, on a trip to Russia organized by the Whitney Museum, I met Leon Botstein, the president of Bard College. We became friends, and he asked me to bring my collection to Bard.

His idea was to create a program around it where students could use the collection to curate exhibitions. A few years later, we had a building with exhibition rooms, and we began the first graduate program for curatorial studies in the US. Later, in 2006, the Hessel Museum was added, since we wanted more galleries to make exhibitions. Now the Center for Curatorial Studies is about to celebrate its 30th anniversary next year, which is very exciting.

You also have a love for international art, which Mariane has mentioned lies at the heart of your collection. Tell me a little about that.

Hessel: Mariane is correct—I love art from all countries and cultures. In my collection you can also find beautiful crafts and historic objects from Mexico, where I lived for many years. I am fascinated by the stories they tell.

I gravitate toward young artists whose work reflects a moment in history. I would say that’s why I collect. I first bought paintings in the late ‘60s in Munich, and, at the time, works by artists like Gerhard Richter, Georg Baselitz, Sigmar Polke, and others were still affordable for my meager budget.

No matter where it comes from, all great art is spiritually uplifting, and it remains an intellectual and emotional challenge for me. So I like to see that represented on a global scale.

Mariane, as a gallerist, do you give a lot of thought to world politics as you are putting together shows?

Ibrahim: Every day, all the time. There is nothing we have done in the past that wasn’t a conduit for a possible social stance. What affects us always, now and moving forward, is the question: How can something so pretty also be so politically challenging? When we look at artists, we consider that. For instance, Lina Iris Viktor works with 24-karat gold. Why would this artist be using something so extremely luxurious, noble, and sought-after? Well, gold is also a signifier of the decay of many civilizations. It also initially belonged to a people, today referred to as “the Third World,” who used it as a spiritual metal intended for connecting with the gods. So how is that not political, to reclaim something deeply personal and spiritual that was taken away from a civilization and completely demystified, sold as a commodity and fetishized, and then restore its use, in a way? Gold was something very precious once.

So, all of the shows we do are meant to challenge stereotypes that have been pre-fixed and meant for you to simply digest. We want to rewrite all of that, and challenge those notions.

This exhibition we’re currently preparing, ”Take Me to the Water” by the photographer Ayana Jackson, is a mind-blowing exhibition that connects Africa, Europe, and the Americas through the history of slavery. Without slavery, there wouldn’t be capitalism. So this is where it all starts—and capitalism oppressed those who caused it. This is an ongoing political and social conversation that we are having through the arts, but without being completely deprived of aesthetics or glamor. We have tried to fight injustice through the visions of our artists. Through their work, we’ve been able to magnify the social changes that we’re trying to emulate.

Marieluise Hessel. Photo by David Lipman.

One thing that you’ve received widespread acclaim for is your focus on African art, and trying to reframe the conversation around it outside of an anthropological lens. Tell me a little about that.

Ibrahim: Happily, we’re not in the business of trying to convince people of the brilliance of our African artists and their aesthetics and work. They’re sought after, but we want to be able to grow with them and take them as far as possible and create more opportunity. From what I hear, a lot of galleries today would like to have African artists on their rosters, because if you don’t it says something about your program. The question surrounding Black artists and African artists is: Are they relevant? Yes, they are. Always. The point is, they have not been integrated into the system because people have created geographic borders. But artists have never wanted to be categorized as “African” or “Asian.”

We’re living in really interesting times, where the top of the pyramidal structure is slowly eroding. There’s a very large contingent of people who are looking for different faces, different works, different perspectives—because what the art world historically has been pushing forward is exceptionalism in a way that was a little bit racialized. It’s as if there’s only one Basquiat, and that means that anyone who looks like him, or comes close to looking like him, will not really be taken seriously.

I personally couldn’t tell you, when it comes to works that I don’t recognize, the difference between a Manet and a Monet. I couldn’t. And so my point is, work may look alike whenever we talk about Black artists who live in the same time and may have the same influences and the same style, but it’s pejorative to say we can only have one. We have to keep talking about it, and pushing the envelope. And we’re comfortable talking about it. Our artists are comfortable talking about that. I also think my Blackness makes it easier to do that. In working with Black artists, that race aspect is absent in some ways, because, you know, I’m Black. We don’t work with an artist because they’re Black. We work with an artist because they’re relevant.

Are you optimistic about the future of race representation in the art world?

Ibrahim: Oh my god, 100 percent. I’m realistic, too. I have to make sure that we embrace changes, that we embrace new collectors. They will be the ones who will challenge the system and change the way that art is selected for the public. I’m also very optimistic about how the work of women artists will also catch up to the desirability of the work of male artists. I’m optimistic that museums will challenge norms and traditions, and will have new personalities who will create unexpected exhibitions that people have never seen before. I’m optimistic that that art is going to be consumed culturally by people who did not have access to it before. It’s also important that we talk about how certain artists have not been able to be in direct touch with the communities they came from, and the benefits of them having that communication.

Chicago is the right place for my gallery, because there are so many important artists here who are connected to their communities. I’m talking about what Kerry James Marshall and Theaster Gates have been doing.

Moving to Chicago was also a political choice. It’s in the middle—the Midwest! It’s perfect. It’s not too far from New York or LA, and it’s the convergence of so many cultures and influences. You have a population that’s 30 percent Black, 30 percent white, and 30 percent Hispanic. You have to deal with all of these cultural disparities, issues, and problems. It’s an amazing place, and this place has groomed the first Black American president. It’s very exciting to be in a place that I consider a political lab for what America should be. I very much want to be part of that cultural and artistic distribution.

Turning back to you, Marieluise, what is something that you’ve tried to teach Mariane? And what is something that you have learned from each other?

Hessel: You know, I didn’t intentionally try to teach Mariane anything. I just talked to her and continue to talk to her about my life, my love for art, and my experiences as a collector. I’ve learned just as much from Mariane as she may have learned from me. We’re really close, and we have an ongoing conversation that we both gain from equally. It’s about staying in touch and communicating whatever is on our minds. We learn a lot from just that.

Ibrahim: She gives me strong advice on how to be careful and never rush into projects—to stay focused on the art itself. As I said, she’s an institution. There’s a kind of invisible protection that I’ve found through her. I feel like her advice guides me.

But it’s also about sharing experiences, and, while we are so different, I think that we’ve also had similar experiences in being autonomous women who have this transient sense of home. There’s this mutual level of having had to find a new place in a new country.

I’m not sure what exactly I’ve taught her, but I’ll say that she has great curiosity about African art, not just as a trend, but beyond that—she feels that the relevance and the aesthetic is already there, and it’s mature. I’ve enjoyed being able to talk to her about that, and help her to access the information, network, and scholars to feed that curiosity. Her approach to it is really a breath of fresh air.

Do you talk about race and representation together?

Ibrahim: We talk about it all the time. Marieluise really gets it, and she talks about bringing more African curators into the conversation. She researches and dedicates herself to learning about it more than anyone I know. She has this incredible international network, and the people on her board are as eclectic as you can imagine. We’re hoping to one day live in a world where you’re hiring people based on their achievements and not their ethnicities, but we’re not there yet. She’s helping to make up those gaps, I feel. It’s an open conversation, and she gives exposure to a lot of curators and professors who are beyond excellent but haven’t yet received mainstream attention. She pushes them forward.

Hessel: Most art is rooted in politics and culture, of course, and we enjoy looking at the stories art communicates. It’s natural that art from Africa or South America looks different than art from Germany, and it’s important to realize that we should honor those differences. Mariane and I discuss all of this.

As two women charting autonomous paths through the art world, what is your main advice for women who want to enter the field? What would you tell them?

Ibrahim: Success cannot rest on one person’s shoulders. Success is not about being on this journey alone. Instead, success depends on the support network you have that will go the long distance with you. When I was younger, I wanted to prove that I could do everything by myself—but then you kind of realize how much more efficient it is to have a network. So, for young women who are entering the art world, find your tribe. Find the people who will give you advice and be there for you. And have tenacity. That’s it.

Hessel: All of that. You must love the arts and make sure you have a solid education. It’s hard work, not a nine-to-five job, and mostly it’s not very lucrative. Success is never easy, so be courageous and don’t care so much about what people think about you and your world. Also—unrelatedly, but this is still important—a good relationship can really enrich your life.