As rock-star artists go, Amedeo Modigliani is an unlikely candidate.

Born in 1884 on a kitchen table in Livorno, Italy, to Sephardic Jewish parents who soon declared bankruptcy, Modigliani was plagued with poor health throughout his life, stricken with pleurisy at the age of 11, and later tuberculosis. He died in 1920 at the tender age of 35.

Despite his premature death, Modgliani’s work was already wildly popular by that time—one of the reasons why fakes and forgeries started popping up so quickly. (In an episode of reality television show “Keeping Up With the Kardashians” a few years back, Kourtney Kardashian believed she and her then boyfriend had inherited an authentic Modigliani. Testing proved it was not the real deal.)

But the proliferation of fakes has not done much to curtail his market. Nor has the fact that the artist’s somewhat singular style of portraiture, in which figures are depicted with elongated necks and almond-shaped eyes, never fit neatly into one stylistic box, like Claude Monet’s Impressionist landscapes or Picasso’s Cubist portraits.

Another obstacle: In the nearly 100 years since his death, there has been no single authoritative entity to oversee and protect his legacy. Further, there are no fewer than five competing catalogues raisonnés (the comprehensive index of an individual artist’s output), which have alternately been criticized for being too strict or too generous with their inclusions.

An expert examines a painting believed to be by Modigliani for Kourtney Kardashian. The work turned out to be a fake. Photo: Courtesy E! via Bustle.

Disputes over his oeuvre have generated lawsuits, accusations of slander, and even death threats. Last summer, a Modigliani exhibition in Genoa came to an abrupt end when police—alerted by an expert that the majority of the show was comprised of fakes—shut it down.

Despite all the chaos, the artist stands today as one of the most expensive in the world, with a current auction record of $170 million and 13 works that have sold for more than $20 million apiece at auction.

An unprecedentedly ambitious retrospective at the Tate in London that wrapped up last month was a blockbuster. The artist’s oeuvre was explored further in a show at New York’s Jewish Museum this past winter, “Modigliani Unmasked,” which presented drawings and sculpture, many displayed in the US for the first time.

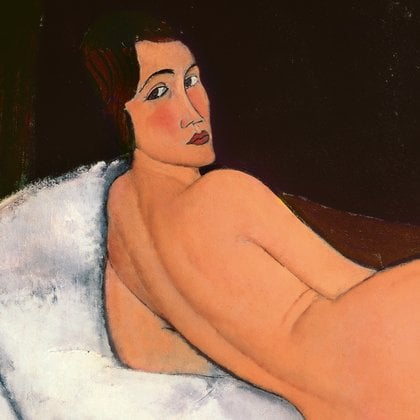

Tonight, Sotheby’s is offering Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917), the largest of a famous series of nudes that the artist painted during his time in Paris. It graces the cover of the Sotheby’s catalogue and was also featured on the cover of the Tate’s exhibition catalogue. One of the most buzzed-about lots this season, it carries the most expensive auction estimate ever placed upon a single work—at $150 million—and could potentially set a new high-water mark for the artist.

How did Modigliani ascend to this vertiginous peak of the Modern art market? Here we take a look at five key factors driving the current global craze.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917). Courtesy Sotheby’s.

1. The Market Makes Up for Lost Time

In 1995, a Modigliani stone sculpture was offered at auction with a relatively modest estimate of $1 million to $2 million and elicited not a single bid. What a difference 15 years makes. In June 2010, a comparable sculpture came on the block at Sotheby’s Paris and scored $52 million, more than ten times its $5 million to $7 million estimate.

In November of that same year, a nude, Nu assis sur un divan (La belle romaine) (1917), more than doubled its $35 million estimate at Sotheby’s New York, silencing the skeptics who said the asking price was too high. “Clearly in that short 15-year period, something changed dramatically,” said Kenneth Wayne, a curator and highly regarded Modigliani expert who is director of the nascent Modigliani Project, a new initiative that plans to release a comprehensive catalogue raisonné.

For years, Modigliani’s prices, while respectable, had lagged behind those of his blue-chip peers like Picasso and Monet. Suddenly, the artist’s profile rose—something Wayne himself had a hand in effecting. In 2002, he organized the acclaimed exhibition “Modigliani & the Artists of Montparnasse,” which traveled from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and then to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. That same year, French Modigliani expert Marc Restellini organized a separate, well-received Modigliani retrospective “The Melancholy Angel” at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. Before that, the artist had not had a major show in more than three decades.

IFAR’s recent Modigliani panel. L to R: Dr. Kenneth Wayne; Isabelle Duvernois; Lena Stringari; and Marc Restellini.

Photo by Steven Tucker. Courtesy IFAR

2. New and Improved Scholarship

Several Modigliani experts spoke at a panel organized by the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) in New York last month. The speakers included Wayne, who, in addition to outlining the scholarly armature of the Modigliani Project (the committee aspect is “absolutely key,” he said, and working with the Modigliani family is “essential”), acknowledged the problematic nature of previous catalogues raisonnés. Five have already been produced by an “unexpected group of individuals,” he noted.

The first one was done in 1929, just nine years after the artist’s death “and could have been invaluable,” according to Wayne. However the author, a German illustrator named Arthur Pfannstiel who later became a Nazi SS officer, “illustrated fewer than a third of the works… basically rendering it close to useless.” (A second edition published in the 1950s contained similar omissions.)

Then, in 1970, another German—a philosophy scholar named Joseph Lanthemann “with no previous experience working on Modigliani,” as Wayne put it—produced a catalogue and “reproduced every work that even remotely looked like a Modigliani,” Wayne said. “That tome is considered overly generous.”

That same year, Italian businessman and consultant Ambrogio Ceroni issued a third edition of his catalogue with 337 paintings and 25 sculptures. Today, the Ceroni compendium is considered “the Bible” in the Modigliani field. The problem? Ceroni never traveled to the United States, where many Modigliani paintings eventually ended up. Wayne and the Modigliani project are confident that 60 “correct” Modigliani paintings should be added to the catalogue, along with three sculptures.

Restellini, meanwhile, was commissioned by Guy Wildenstein via the Paris-based Wildenstein Institute in 1997 to produce a Modigliani catalogue, but that project was terminated in 2015. Restellini, who also spoke at the IFAR panel, said he is still working on a catalogue independently, and that he has made substantial headway, including establishing a protocol for paint-pigment analysis. He plans to release his catalogue online in about a year’s time.

Restellini also revealed it was he who was was responsible for alerting Italian authorities to the existence of fakes in the Genoa show, under what he described as “an authority by the expert right granted to me” by a Paris court. “It was not two to five works”—as some said—”but more than 16 notorious ones that we have known about for years that were shameless recycles in the show,” according to Restellini. “This was not a question of a few mistakes but quite something else.”

The independent specialist, who has often urged for physical destruction of known fakes, compared them to “cockroaches,” saying, “if not destroyed altogether they never fail to reappear.” The stakes are high: Restellini said he has received death threats in the past for calling out Modigliani fakes.

X-radiograph showing an earlier figure painted beneath the surface of Modigliani’s Portrait of a Girl. Image © Tate

3. Technological Advances

Ahead of the Tate’s recent major Modigliani exhibition, the London museum initiated the Modigliani Technical Research Study (2017–18) to take advantage of the fact that so many Modigliani paintings would be in the same place at the same time. More than a dozen institutions, including lenders to the show and other institutions whose works were not permitted to travel, such as the Barnes Foundation and the National Gallery of Art, contributed to the research.

Using techniques that sound as if they were invented for a spy thriller—X-radiography, infrared reflectography, ultraviolet and visible-light photography, and light microscopy—conservators and experts studied everything from Modigliani’s masterful drawing technique to the various background primers used on the canvas. Even the “weave,” or thread count, of the canvas was used to establish commonalities in the materials and working process.

The findings were presented in a series of articles for Burlington magazine, and Isabelle Duvernois, conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Lena Carol Stringari, chief conservator of the Guggenheim, presented some of their findings at the IFAR panel. “The goal is to make comparisons with other works and understand the working process of the artist,” explained Stringari. “Although we point out inconsistencies, I am not in the business of authentication,” she added.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché, 1917–18.

Courtesy Christie’s New York.

4. Global Appeal

It’s no accident that Sotheby’s chose to unveil its latest trophy lot in Hong Kong, where growing ranks of wealthy buyers have been homing in on Western masterpieces. The last major Modigliani nude, the one that set the current auction record, was sold to Chinese taxi driver-turned-billionaire Liu Yiqian, who plans to present the work at his Long Museum in Shanghai.

“Modigliani appeals to a wide audience,” Leslie Koot, a founding director and board member of the Modigliani Project, told artnet News. “But with the escalating prices for his work—especially for nudes, which rarely come to auction and are his most coveted works—only the ultra-rich can afford his masterpieces now.”

Unveiling the work in Hong Kong “makes all the sense in the world, and is a good business decision,” she said. “Furthermore, the purchase of the nude by the Asian collector two years ago may provoke a ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ effect among other, ultra-rich Asians.”

The interest is by no means Asia-specific, however, said Simon Shaw, Sotheby’s worldwide co-head of Impressionist and Modern art. “This is an A+ picture,” he said. “It has just as much resonance for American, European, Russian collectors, who’ve also had major bids on Modigliani in the past.” Notwithstanding the risqué subject matter, there is certainly interest in Modigliani in the Middle East as well, Shaw noted. “How often can you say, ‘Here’s an artist that there’s a big buzz about at the moment, and nobody will ever buy a better example than this’?”

Modigliani in his studio, photograph by Paul Guillaume, c.1915

©RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) I Archives Alain Bouret. Image: Dominique Couto.

5. Seeping Into Pop Culture

One of the most entertaining aspects of the IFAR night, and proof positive (if any were needed) that Modigliani has crossed into the mainstream, was Wayne’s introductory presentation of the wide-ranging influence the artist has had on today’s popular culture. He rattled off a slew of examples in which Modigliani has made an appearance, including novels and graphic novels, Laurent Seksik’s recent play Modi, and Woody Allen’s 2011 film Midnight in Paris, where a character played by Marion Cotillard says she has just broken up with an Italian Jewish artist, prompting the response, “You were dating Modigliani?”

Wayne also mentioned the James Bond thriller Skyfall, in which a replica of a Modigliani that in real life has been stolen and remains missing is the target of a connoisseur’s admiration—right before he is assassinated with a bullet to the back of the head. The artist has even furnished inspiration for rom coms: In the 2008 romantic comedy Made of Honor, Michelle Monaghan plays a so-called “director of acquisitions” at the Met whose favorite artist is Modigliani.

As if that wasn’t enough broad-culture cachet, the Modernist master may even seep into the world of sports. John Magnier, the billionaire Irish horse-breeder and art collector who is selling the $150 million-estimated nude, owns a horse named Modigliani, a three-year-old colt so named for an association with “excellence and success,” according to Wayne. When a slide of the horse came up during a recent presentation, the Modigliani scholar said with a smile: “Note the long neck.”