Photo: maría josé/Flickr.

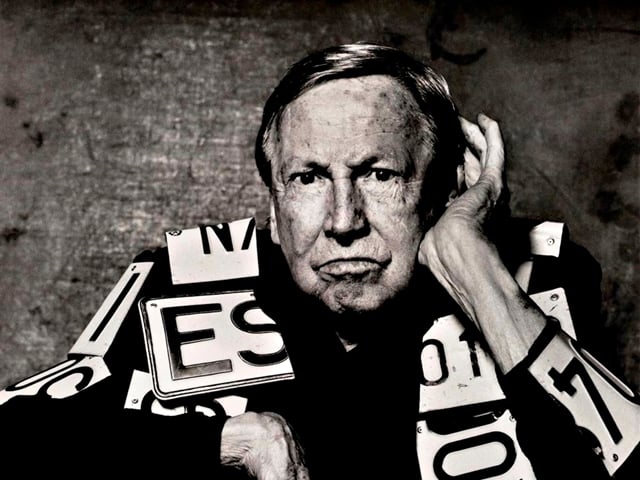

Robert Rauschenberg with his tongue stamped “Wedding Souvenir, Claes Oldenburg” at Oldenburg’s wedding (1966).

Photo: Dennis Hopper, via grey not grey.

“No one could mistake a Rauschenberg for the work of anyone else,” Calvin Tompkins wrote of artist Robert Rauschenberg, whom he profiled in the February 29, 1964 issue of The New Yorker. “It can be argued that his personal taste must be the guiding force in all his work, and that what his paintings really express, in defiance of his wishes in the matter, is his own unique view of life.”

This “unique view” is responsible for some of the more clever conceptual works for which the artist is known, such as the subtraction drawing he employed in Erased de Kooning (1953) as well as the mutability of his White Paintings, where passing shadows became “drawn” on the canvases. Rauschenberg worked across media and with a range of materials; he was a serial scavenger of found objects. He is credited with moving American art away from AbEx and toward pop art, although his work stands away from any label you try to pin on it.

If you live in New York, you can celebrate what would have been his 90th birthday tonight at Pace Gallery, with the opening of “Anagrams, Arcadian Retreats, Anagrams (A Pun).”

See the reasons why we still love Rauschenberg below.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning (1953). Image: Courtesy of SFMOMA.

1. “It’s not a negation, it’s a celebration.”

Rauschenberg showed up with a bottle of Jack Daniels, not anticipating a favorable response from Willem de Kooning. But when he approached de Kooning about erasing the work, the irascible Dutch American artist was all for the idea.

Watch Rauschenberg speak about his Erased de Kooning (1953) in the video above.

John Cage in his Model A car at Black Mountain College. Photo by Robert Rauschenberg. Image: Courtesy of Phaidon.

2. Rauschenberg “updated” his friend’s painting without his consent.

A friend from his Black Mountain college years, John Cage, may have been bitten by bedbugs while sitting on a mattress at Rauschenberg’s apartment. Cage then offered his friend a stay at his while he was out of town. As a token of gratitude, Rauschenberg allegedly painted over an artwork previously gifted to Cage, to the musician’s dismay.

Robert Rauschenberg, Franciscan II (1972).

Photo: via escapetonewyork.net.

3. Rauschenberg’s mother had wanted to wash his MoMA aquisition, Franciscan II (1972).

After the artist told his mother that the museum had just acquired the artwork, she replied “Tsk, tsk, tsk. Isn’t that something. There’s just no accounting for taste.”

Robert Rauschenberg, Gull (Jammer) (1976).

4. “Excess is expressionless without restraint.”

When questioned about his his Jammers series during a conversation with Leo Castelli and Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Rauschenberg shared some wisdom given to him by his legendary instructor and Bauhaus founder, Josef Albers, while he was enrolled at Black Mountain College.

See the artist explain his theory and methods in the video above.

“Speaking in Tongues” by the Talking Heads, with limited-edition LP version by Robert Rauschenberg.

5. He won a Grammy.

Rauschenberg designed the limited-edition LP version of the Talking Head’s album Speaking in Tongues. The motif was reminiscent of his work included in the boxed collection Artists & Photographs (1970) The artist won the Grammy in 1983, making it the “first and only” award the band received while active.