Frank Stella, Tomlinson Court Park (1959). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

This past Friday, the Whitney Museum opened Frank Stella’s third retrospective, with over 120 works ranging from paintings to sculptures, drawings to maquettes, prints to reliefs. Stella already holds the record as the youngest artist to be the subject of a major museum retrospective—his first being at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970, when he was only 33 years old. Now is the perfect time to take stock of this prolific artist’s career, and look at how his legacy continues to influence art being made today. To that end, we’ve put together a selection of younger artists that we can’t help but feel are particularly indebted to Stella, and his numerous contributions to the history of abstraction.

For a more a comprehensive overlook of Stella’s evolution as an artist, you should of course visit the retrospective at the Whitney, running through February 7, 2016, but for now, let’s go on this mini survey below.

Black Paintings (1958–1960)

Left: Ned Veena, Untitled (2011). Courtesy of Christie’s London. Right: Sermin Kardestuncer, Untitled (2014). Courtesy the artist and Pierogi.

When Stella first arrived in New York in 1958, Abstract Expressionism dominated the art scene. With his Black Paintings series, Stella deviated from the prevailing aggressively gestural style of his day by removing the artist’s hand completely, stripping painting down to simple geometry. All the work in this series sticks to a simple black and white palette, using lines to construct grid-like mazes and concentric rows of even paint. The flat planes and precise lines of the Black Paintings helped introduce New York to Minimalism, and the lasting influence of this movement can be seen in the work of countless artists to this day. Ned Vena’s work may be almost identical to Stella’s in appearance, but it differs significantly in its method. Vena uses his own mix of modern technology and everyday materials to recreate Stella’s methodical technique, while Turkish artist Sermin Kardestuncer uses thread and silk paper to stitch together linear compositions that also recall Stella’s early work.

Concentric Square Paintings

Top: Frank Stella, Double Concentric Squares (1973). Courtesy of Simon Capstick-Dale Fine Art.

Bottom Left: Jim Lambie, Metal Box (Tahiti) (2014). Courtesy of Paddle8. Bottom Right: Chul Hyun Ahn, Untitled 617 (2014). Courtesy of C. Grimaldis Gallery.

Beginning in the early 60s, Stella began moving away from the Black Paintings and started producing work that explored a broader range of color, exemplified in his Concentric Square paintings. During this time, he focused on pared-down squares and color scales on a geometric, flat surface. Korean artist Chul Hyun Ahn utilizes built-in light in his sculptures to take his playful exploration of color one step further, creating optical and bodily illusions with fluorescent light. Similarly, Jim Lambie’s works, such as his Metal Box installations, use layers of color in a three-dimensional formats to make a strong visual impact. Both artists channel the ideas of Minimalism while still delivering work that looks and feels contemporary.

The Protractor Series

Top Left: Greg Bogin, Accumulation of meaningless Moments (2011). Courtesy of Galerie Clemens Gunzer. Top Right: Frank Stella, River of Ponds I (1971). Courtesy of Leslie Sacks Contemporary. Bottom Left: Alban le Henry, sunset (2012). Courtesy of www.albanlehenry.com. Bottom Right: Frank Stella, Sinjerli Variation III (1977). Courtesy of Vertu Fine Art.

By the mid-1960s, Stella began deviating from the traditional rectangular canvas and started incorporating curved shapes in his custom supports. The asymmetry and energetic forms of his Protractor series are composed of overlapping rainbows of color conveying the illusion of depth. Similarly dynamic geometric shapes can be found in the works of contemporary artist Greg Bogin and designer Alban Le Henry. Both Bogin’s electric color gradients and Le Henry’s playful product designs echo the simple angles and curves Stella created with a protractor.

Sculptural Reliefs

Left: Frank Stella, Treat My Daughter Kindly (1986). Courtesy of Dranoff Fine Art. Right: Hyon Gyon, Archbishop (2013). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

In the early 70s Stella started pushing his two-dimensional work into the third dimension. This is known as his relief period, and Stella playfully refers to these pieces as his “Maximalist” paintings. Stella introduced wood and aluminum to his materials, achieving wildly dimensional and layered compositions. Though the works are a departure from the flat planes of his early repertoire, they are still heavily dependent on geometry—though this geometry is decidedly less regular, and more trapezoidal.

South Korean artist Hyon Gyon similarly explores the world between painting and sculpture, constructing elaborate reliefs that incorporate a wide range of materials such as yarn, beads, feathers, pottery shards, and wax. Before pursuing a career in the arts, Hyon Gyon worked as a designer of traditional Korean clothing. The influence of her prior career can be seen in her choice of materials and in the textural qualities of her work, and whereas Stella focused on aggressively edged geometry, Gyon focuses on creating intuitive, organic abstraction.

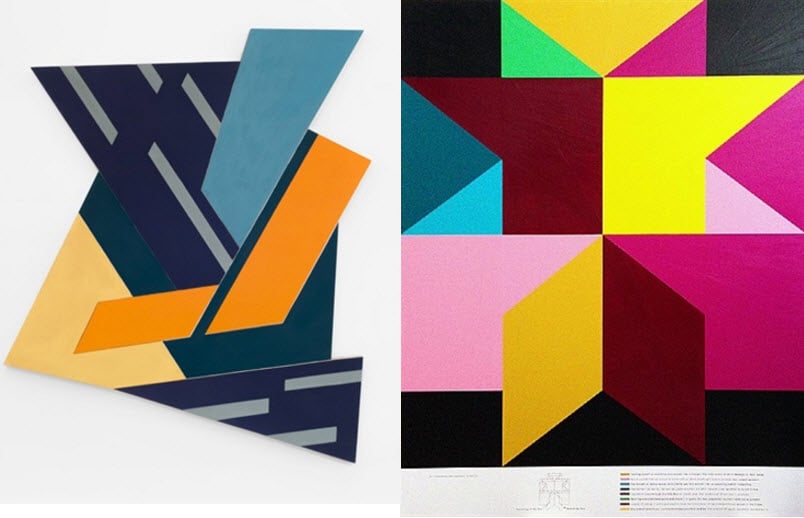

Polish Village Series

Left: Frank Stella, Felsztyn II (1971). Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery. Right: Andrew Kuo, If I Could Re-Do Tuesday 12/25/12 (2012). Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery.

In The Polish Village series (1970–74), Stella explored Cubism and Russian Constructivism through his fascination with the avant-garde design of wooden Polish synagogues and Polish villages built between the 17th and 19th centuries, extrapolating simplified, colorful compositions that echo rather than copy their source material. A corresponding approach is present in the work of contemporary artist Andrew Kuo. Whereas Stella found inspiration for The Polish Village series in historical, external material, Andrew Kuo uses internal sources such as thoughts, words, and phrases to create symmetrical abstract compositions. Kuo translates emotions and daily routines into colors and forms by labeling his feelings and thoughts, and reorganizing his internal monologue into colorful charts that become geometric abstract paintings. Kuo draws everything meticulously by hand, without assistants, letting words dictate his process.

Sculpture

Left: Frank Stella, djaoek (2004). Courtesy of FreedmanArt. Right: Tomas Saraceno , Biosphere 06 (2009). Courtesy of Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Stella’s most recent body of work falls squarely in the sculptural realm, consisting of both small-scale pieces and large-scale public installations. His sculptures have evolved over time into free-form, complex shapes that continue Stella’s lifelong investigation of abstraction, featuring daring, swooping compositions of poured and cast metal. Argentinian artist Tomas Saraceno’s installations and sculptures employ a multi-disciplinary artistic practice, inspired by his background in architecture and influenced by his interest in space exploration. Saraceno’s spatial biospheres resonate with Stella’s later geometric sculptures. Both artists use space itself as a to create complex works on a monumental scale.