Trends in the art market have a way of earning cheeky nicknames. There’s zombie formalism. Identity figuration. Zombie figuration. This auction season, a new trend seems to be surfacing that merits a moniker: naïf brut.

In recent years, the market has gone gaga for artwork that would seem to appeal mostly to children. Take Jordy Kerwick, who unabashedly creates what his kids would think is “awesome,” according to his gallery’s website. His two-headed tiger figures have become a staple at art fairs around the globe, and a piece of his sold for £200,000 at auction in London. Robert Nava polarized the art world with his gestural paintings of animals which, scaled down and put on printer paper, could feasibly have been sketched in magic marker by the kid next door.

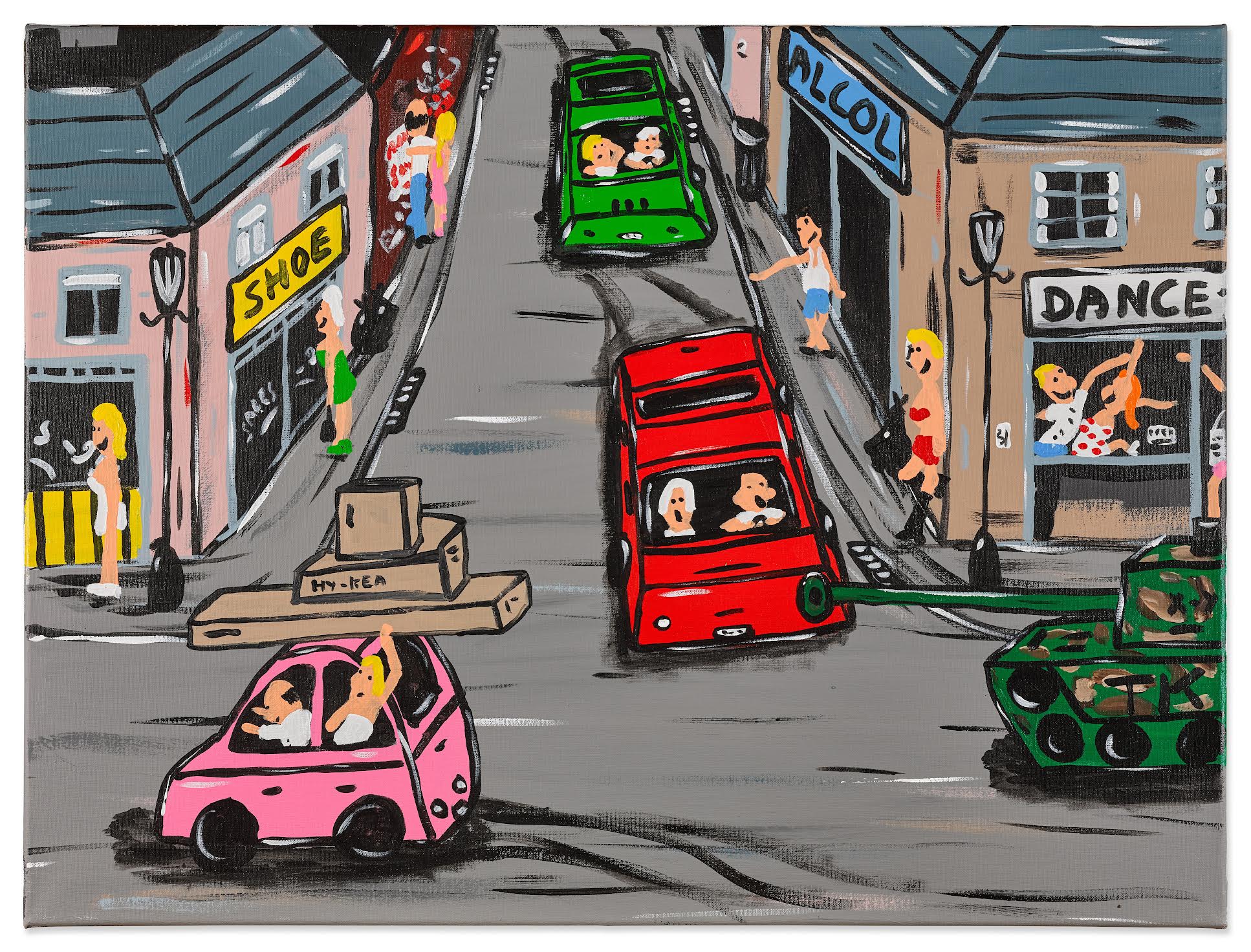

Add Belgian painter Albert Willem to the list. Willem is quickly climbing the charts and this season, he has one painting up for sale in Sotheby’s contemporary art day auction. Titled Pilgrim Street 8 (2021), and carrying an unassuming estimate of $8,000 to $12,000, the piece sold for $69,000.

“Albert Willem made his auction debut just six months ago at Sotheby’s, yet we had seen huge demand for his works from collectors long before then,” said Isabelle Paagman, a senior international specialist in contemporary art based in London. Paagman added, “People love Willem’s aesthetic: it’s bright, eccentric, and playful, and his paintings always have a narrative, packed with a lot of action and humor. They make people smile and undoubtedly carry an energy that emanates from these imagined stories.”

Willem’s works have been consistently outpacing their estimates by a factor of 10 or more. His current record was achieved just last month at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, where his piece Snowbound 大雪紛飛 (2021) raked in a staggering 1.8 million HKD, or about $225,000, on an estimate of 100,000 HKD to 150,000 HKD, or $13,000 to $19,000. Fourteen works have sold this year, and half have hammered for over $150,000 on estimates typically around $10,000 to $15,000.

According to Jonathan Dodd, of Willem’s gallery Waterhouse & Dodd, Willem’s work does exceptionally well with young collectors in Asia—a set who notoriously have quite a bit of money to spend on youthful, lighthearted artwork (think KAWS, Yoshitomo Nara, and the like). But European collectors are giving him a second look, too.

“Albert’s works are very different to most of the works being produced in today’s art world and his success, whilst a positive surprise to us, isn’t totally a shock, given how well he’s been received by people and collectors who stand in front of his works, or see it online,” said Dodd.

But, as interesting as Willem’s story is through the numbers, it’s also compelling to look at his rise through his aesthetic sensibility. The paintings are simple, unvarnished, sometimes half-baked. On the one hand, they boldly assert that the artist’s technical skill dawdles emphatically at elementary level. On the other, he is able to harness the distilled, pure energy of a novice who is unconcerned with competing against the canon, and therefore the works are absent of pretense.

“You have a sense of a very real personality behind the painting, a very open and likeable person,” said Dodd of his works.

Albert Willem, The nightlife area 3 (2020). Courtesy of Waterhouse & Dodd.

It wouldn’t be condescending to say that Willem’s works are, in fact, childlike. The 43-year-old artist rediscovered the craft at age 36, after not having picked up a paintbrush since he was 12. Going to university and raising a family distracted him from art, but he described returning to his practice as a “midlife crisis.”

He maintained an interest in art, however, citing Pieter Breughel the Elder as his favorite artist. “I’ve tried to use his references and bring it into today’s world with a humorous twist,” Willem told Artnet News over email. Once he gained a critical mass of works, he started uploading pictures of them to his Instagram, which is where he said he found his first collectors. From there, he got his first show at Hyde Gallery in Moscow, which is where Dodd discovered his work. “I was really happy when I finally got a gallery who allowed me to show my works in a more serious context,” Willem said of his decision to start working with Waterhouse & Dodd.

Facile humor is a focal point of Willem’s paintings, and each piece seems to have a David Shrigley-esque punchline. For instance, The Sound of Horror (2021), which sold at Sotheby’s New York this September for $164,00 on a $15,000 to $20,000 estimate, depicts a massacre at a drive-in movie theater where The Sound of Music is playing on-screen. The hokiness is sort of the point, Dodd said. “I think especially among younger collectors, the fact that the jokes can be understood immediately, without endless, abstruse cross-references, is very refreshing.”

“Most clients like the humor, which normally comprises a good joke well expressed,” Dodd continued. “And then there is the addition of secondary characters and incident. Thus the painting can be understood or ‘read’ very quickly, but then there’s lots more to repay going back to.”

Willem’s first solo show at Waterhouse & Dodd opens in London next year, and the gallerist told me that the tags on works for sale will be “significantly less than auction prices,” and that each work will carry a clause in the sale contract stipulating that the buyer can’t resell the work for three years.

For anyone rolling their eyes at the story arc of a hobbyist painter suddenly thrust into a market hot seat, rest assured that this was never really part of Willem’s plan. He himself feels pretty stunned by his overnight success, and expressed that his only long-term goal is to keep having fun while painting and keep his sense of humor about it.

He summed it up thusly: “This being the 21st century, a lot of crazy things happen in the world. I guess this is just another.”