Christie’s is kicking off the new year with news of an exciting discovery for collectors of American art and folk art.

At its upcoming sale in New York on January 24, the auction house is offering a rare double-sided portrait by 18th-century artist Ammi Phillips (1788–1865). Phillips was an itinerant portraitist who worked for more than 50 years and produced as many as 2,000 portraits, according to the National Gallery, in Washington, D.C. Because he embraced so many disparate styles, his works were at times thought to be by several different artists.

In the particular portrait in question, the work is painted on both sides in “a format which has not been documented to Phillips before discovery of this work,” according to Christie’s.

Outstanding questions surrounding the examination of the work include the identity of the sitter, who is believed to be the same person and rendered in a similar pose but with major differences in the portrayal and accessories she wears.

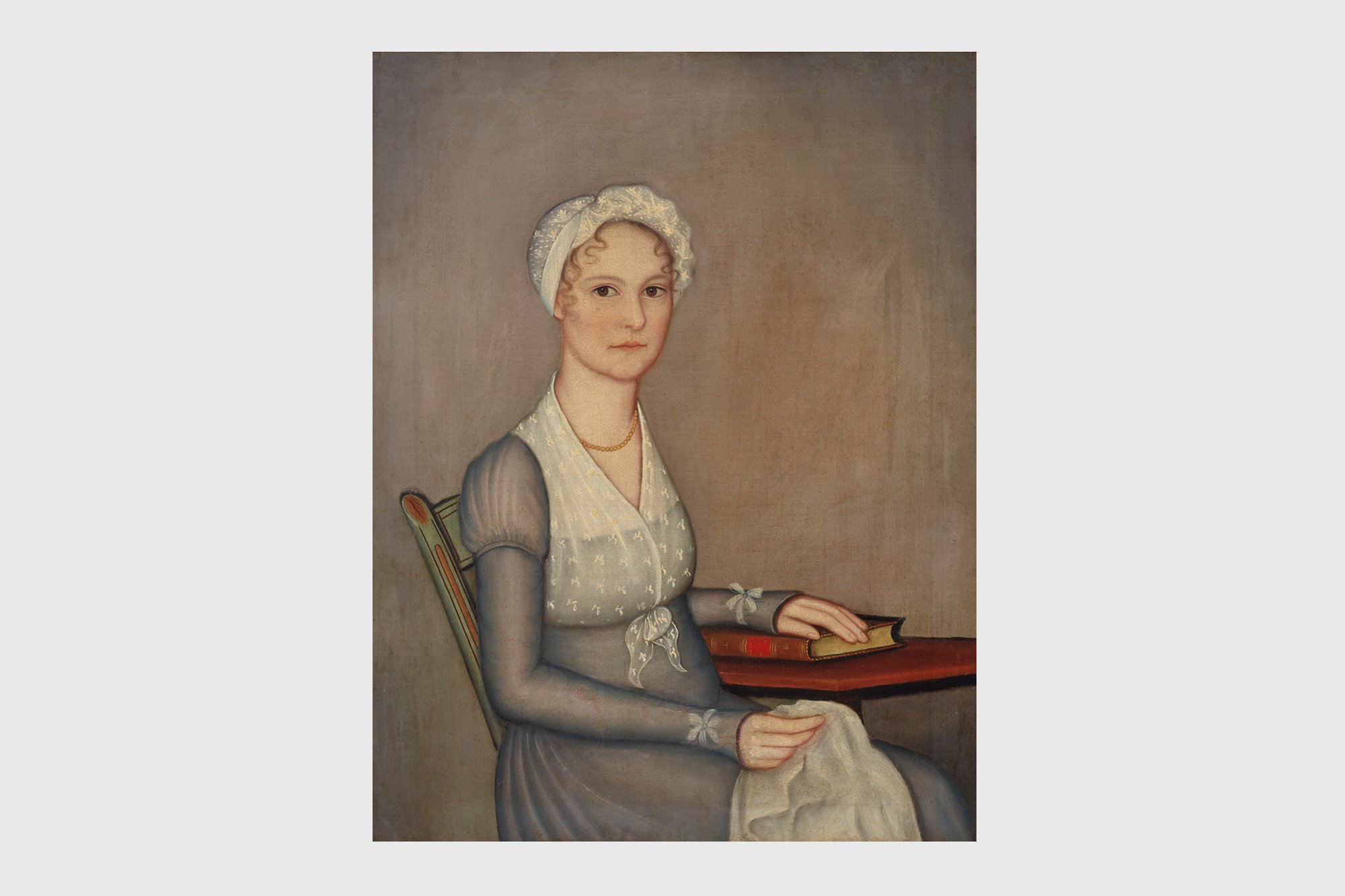

Ammi Phillips, Portrait of a Woman (Double-Sided) (Circa 1810). Image courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd.

For instance, each sitter is installed in the same pale, greenish-blue fancy chair and holds a lace handkerchief in her right hand with the other resting on a red book set atop a table. While the painting on the reverse shows a woman who is slightly larger in scale, with a wider face and higher forehead, the primary side “presents more feminine,” according to Christie’s. Her face is framed with softer ringlets, her nose is smaller, and her lips are more balanced. The overall effect creates “a more elegant portrait,” compared to the reverse.

Why did Phillips approach the work this way? It seems probable that the version seen on what is now the reverse was a rejected commission, according to Christie’s catalogue. “The sitter or family was not pleased by Phillips’s work and being ever resourceful, the artist repurposed the canvas to produce a portrait that was then deemed acceptable.”

According to the Artnet Price Database, the record for the artist at auction is $3.8 million, set at Christie’s in January 2022, for Woman With Pink Ribbons (ca. 1833). The PDB lists more than 270 artworks that have been offered at auction. This work has a far more modest estimate, at $40,000 to $80,000.

Mystery remains about the recent ownership, since the painting was discovered in an abandoned storage unit in California earlier in 2024, Cara Zimmerman, Christie’s head of American furniture, Folk and Outsider Art, told me. “The person who acquired the contents of the unit knew this painting was likely something special, and he reached out to us for thoughts. Our jaws dropped when we saw his photographs, and we had the portrait with us at Rockefeller Center within the week!”

She added that someone clearly prized the work enough to store it. “That it had been brought to the West Coast indicates someone cared enough to move the work across the country. Perhaps a descendant of the original sitter? A collector of Folk Art?”

Phillips, who was born in Colebrook, Connecticut, often traveled through western Connecticut and Massachusetts and through New York state. Advertisements in the Berkshire Reporter show that he was offering his services as a professional artist in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, as early as July 1809, according to the National Gallery bio.

Zimmerman said both sides of the portrait were visible when the auction house physically received the piece, “but interestingly, the secondary side was partially obscured by its stretcher.” Specialists eventually took it off its stretcher and the conservator constructed a larger strainer that supports the canvas without obscuring the work.

“We of course have kept the earlier support, which will be sold with the painting and can always be reattached should the new owner want to display the piece that way,” Zimmerman said, adding: “This painting begs to be displayed with both sides visible. It tells a unique story this way about the artist and his process as much as the sitter.”

As to the identity of the sitter, the auction house has mentioned three possibilities: that it is a member of the Dorr family of Rennselear and Columbia counties in New York; that it is a member of the Spicer family of Pittstown, also in Rennselear county; or that the sitter was a guest visiting the Dorr or Spicer family at the time the portrait was created.

“Our working theory is that the same woman is depicted on both sides of the canvas, based on the birth/beauty mark seen on the woman’s cheek in both paintings. However, the woman is much more alluring on the primary side—her features more refined, her gaze more direct,” Zimmerman said.

Early American portraits were prized and expensive possessions that often descended in families, she noted. “They move through time and space and continue to be displayed in many ways for many reasons.” When Christie’s exhibits the work soon in a pre-auction viewing, it will be shown on a pedestal with both sides visible.

Zimmerman added: “Hopefully, this tactility will appeal to institutions as well as private collectors, as the work tells many stories: of a beautiful young woman, of a talented artist embracing the needs of his patron, of an object moving through time and existing in space. I feel honored and excited to handle this work.”