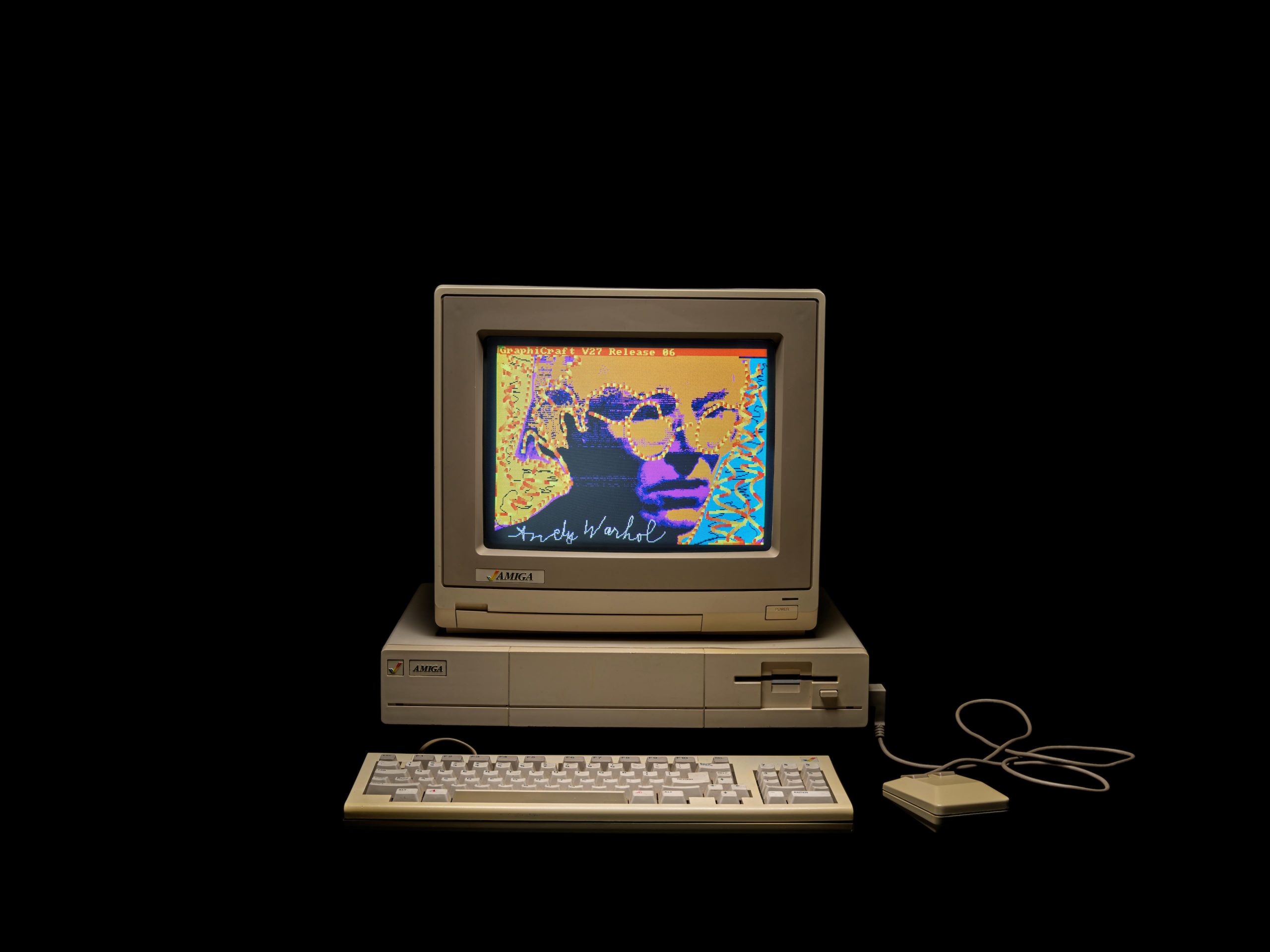

Last week, at an auction held at Bonhams in New York, a unique Andy Warhol work was on offer. It wasn’t one of the Pop artist’s famous silk screens, nor one of his more experimental videos. Instead, it was a floppy disk containing nine original digital artworks the artist made on an Amiga 1000 computer in 1985, one of the first personal computers to offer color, sound, and animation.

“During this morning [Friday, June 14, 1985] I went down to the Seagram’s building for that ‘How to Paint’ video thing that the computer company, Commodore, wants me to be a spokesman for,” Warhol recounted in his diaries. “And I guess I got the job […] It’s a $3,000 machine that’s like the Apple thing but can do a hundred times more.”

The subjects of the works include a sampling of Warhol’s most iconic themes—portraits of Marilyn Monroe, a Campbell’s soup can, a dollar sign, and even a self-portrait—but they were created in what was then a completely new and emerging medium: software programmed on a personal computer.

Normally, Warhols of these subjects in any format will spark heated competition. Similar digital images discovered in 2011 by the artist Cory Arcangel on floppy disks stored at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh brought in $3.4 million when auctioned as individual NFTs at Christie’s last year. At Bonhams on May 19, the lot—consisting of an Amiga 1000 computer plus nine original Warhols (eight of them animations) contained on a floppy disk, previously owned by a former treasurer at Commodore—received only a single bid, of $252,375 including fees.

The divergent result illustrates how the market for NFTs—despite being a newer, untested technology—has overtaken the much smaller, more niche market for early and historical digital assets.

Warhol Amiga 1000 Series as part of the collection of Don Greenbaum, Courtesy Bonham’s, 2022

The Warhol disk at Bonhams was purchased by the Carl and Marilynn Thoma Foundation, a Santa Fe-based nonprofit with a focus on art made with computers. Jason Foumberg, the curator at the Thoma Foundation, chalks up the broad price differential between the Bonhams lot and the Christie’s NFTs to two factors.

The first is, of course, the current hype around NFTs. Secondly, utilizing and displaying vintage technology like the Warhol disk often requires special skills outside the realm of art conservation. The Warhol disk and Amiga computer were restored by its original owner, Don Greenbaum, a former treasurer at Commodore, who was able to recover the disk’s contents by recreating the original software environment (first called GraphiCraft, later called Propaint) under which Warhol produced them.

“Traditional collectors fear equipment obsolescence,” Foumberg told Artnet News, adding that there seems to be a “reluctance by museums and collectors to purchase vintage technology.”

Amelia Manderscheid, vice president and senior director for postwar and contemporary art at Bonhams, says that the Warhol Amiga remains an important discovery that illuminates the oeuvre of one of the 21st century’s most important artists. “This is the first animated art we’ve ever seen by Warhol,” she said, speculating that the price disparity between this Amiga computer/floppy disk sale and the NFTs may be “tied to the exponential increase in the value of cryptocurrencies.”

Even the lowest-performing of the single, static Warhol NFTs at Christie’s last year fetched $250,000—despite the fact that their format raised questions of authenticity among experts. In its bid to lure wealthy crypto investors, the auction house marketed the five digital images as “machine made,” with Christie’s increasing the original images from 320 x 200 non-square pixels to 4,500 x 6,000 pixels for their sale as NFTs.

According to Golan Levin, however, who heads Carnegie Mellon’s Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry lab, which together with Arcangel helped recover the files from Warhol’s computer between 2011 and 2014, the enlargement fundamentally altered the originals. “Christie’s was blithely saying you’re getting five original artworks,” Levin said in an interview with ARTnews last year, adding, “[they’re] not accurate. You’re getting this kind of proxy or stand-in.”

Warhol Amiga 100 Series as part of the collection of Don Greenbaum, Courtesy Bonham’s, 2022

Jehan Chu, an art collector and former auction-house specialist who bought one of the Warhol NFTs at Christie’s last year, disagreed, telling Artnet News that the issue is not so much whether one format is more valid than the other. “As a collector, what I care about is the uniqueness of it, I do not care that the format or pixels were changed,” he said. “Like a painting retouched for auction, I’m happy that when I present this work, it is in the highest fidelity possible while remaining true to the spirit of the work.”

Chu bought the NFT of Warhol’s Untitled (Flower) for $525,000, more than double what the floppy disk and Amiga computer went for with all nine images restored.

He added that while it is important to understand that the reproduction rights over the images stored on the floppy disk and the NFTs both remain under the strict control of the Warhol Foundation, ultimately the tension between the two media should not be confused with the uniqueness of the works made by Warhol’s hand.

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Flower) (ca. 1985), minted as an NFT in 2021.

© The Andy Warhol Foundation.

Adding to this sentiment, others believe that NFTs will be more conducive for establishing provenance in the long term. According to Ryan Zurrer, founder of Dialectic.ch, digital art collector and owner of Beeple’s HUMAN ONE, NFTs are merely a tool by which to establish ownership, not to be confused with the actual art itself.

“We will continue to have issues around the provenance of legacy digital art,” Zurrer told Artnet News. “In my view, that brings credence to the value of NFTs for establishing provenance and digital scarcity.”

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Self-Portrait) (ca. 1985), minted as an NFT in 2021).

© The Andy Warhol Foundation.

Noting Warhol’s longstanding commitment to medium-agnostic experimentation, the curator and technological savant, Shumon Basar, agreed, stating that the Amiga series establishes Warhol’s digital footprint.

“In a way,” Basar said, “this is also part of the medium’s exciting new qualities—how it’s going to be claimed and counterclaimed. Andy’s engagement with the Amiga computer at the time may have looked like crass product endorsement, but at the same time we could also say that every new art medium is also the invention of its future legal contestation.”

Still, Foumberg believes he snagged a bargain on works whose historical significance only stand to grow. “The works are also all digitally signed by hand. You have really never seen Warhol artworks like these, they jump off the screen,” he said. “Warhol certainly was comfortable with brand synergy and capitalism, but beyond that this artwork embodies an ethos of early computer art. Having a 1985 Warhol in our collection, perhaps one of the earliest examples of PC-made art in color, and animated, helps us tell the history of digital art in its fullness.”