When Jill Miller found a photograph of her face had been used without her consent on an Ariel Pink album cover, she could have addressed the violation in any number of ways. Calling it out online maybe, or even bringing suit. But why do that, she reckoned, when, as an artist, she could respond with an art project?

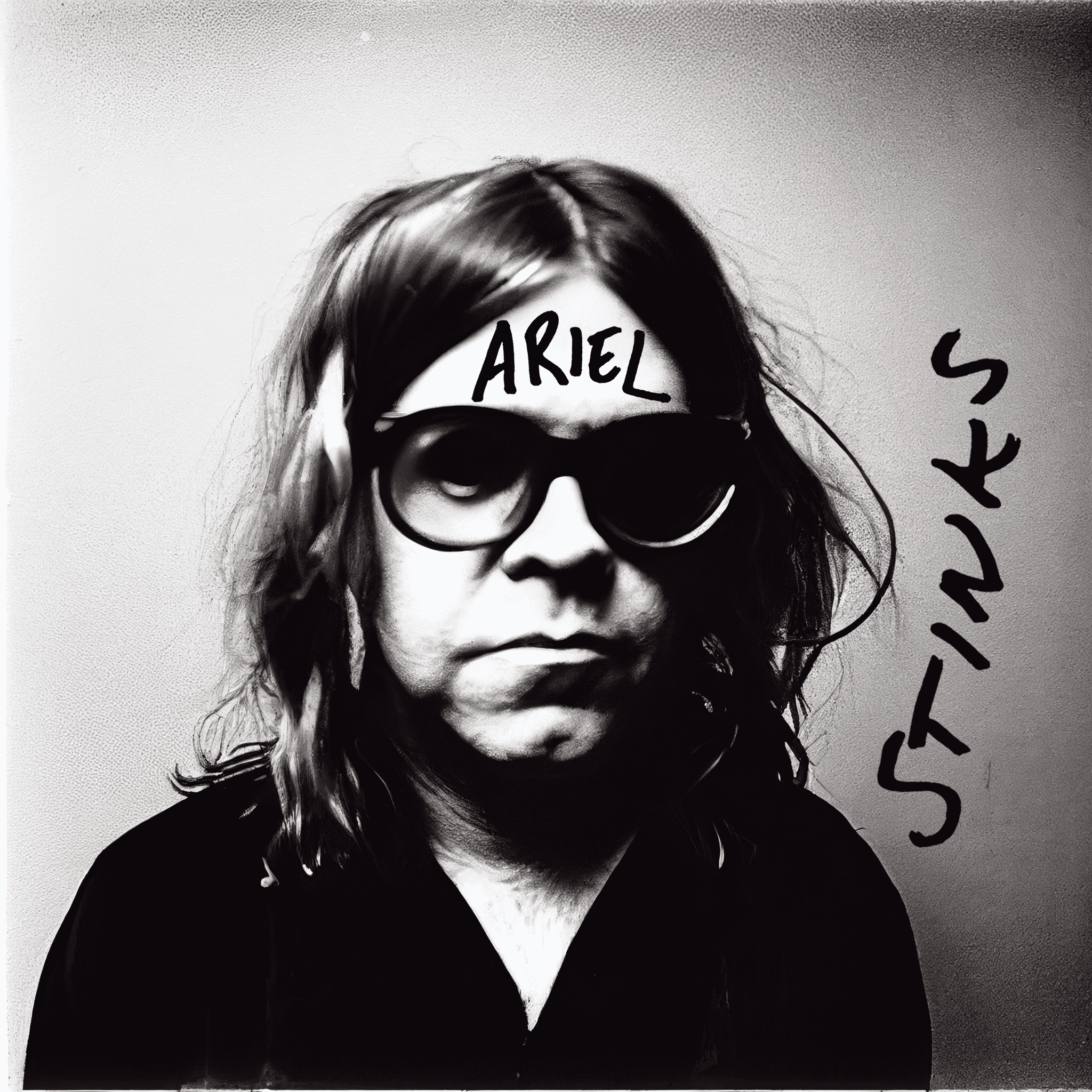

In 2006, musician Ariel Pink released Thrash and Burn, a 36-track compilation of his late-‘90s lo-fi experiments, its cover featuring a close-up image of Miller’s face. Across her forehead was scrawled his name “ARIEL,” and beside her face the word “STINKS.” The cover art was credited to visual artist Michael Rashkow; its subject remained unnamed.

During lockdown, Miller came across her own face on Pink’s record sleeve, and was confused. She had no idea how he had come to possess the photograph—and had certainly not granted permission for her image to be used on his album cover.

In subsequent DMs with Pink over Instagram, the L.A.-based singer simply directed Miller to Rashkow, who turned out to be her former classmate at UCLA. Back in the early 2000s, Miller was earning her MFA at the university and hosting regular open studio visits, where Rashkow likely snapped her picture.

The cover of Ariel Pink’s Thrash and Burn (2006), featuring a photograph of artist Jill Miller. Photo: HEM

That image would somehow end up in the hands of Jason Grier, the director of the music label Human Ear Music, which released Thrash and Burn (then reissued it in 2013). He claims his “next-door neighbor” designed the album’s cover, before he sought and received Pink’s sign-off on the artwork, though not Miller’s authorization.

“My initial thought was, ‘how rude,’” Miller told Artnet News of her reaction to seeing her face on Pink’s album sleeve. “And my follow-up thought was, ‘how predictable.’”

Her next move? Creating 50 alternate album covers of Thrash and Burn, intended to replace—and parody—the original.

Generated using A.I. software and released as NFTs, these digital works are grouped into four themes, largely centering Pink in a variety of absurd scenarios. There’s Ariel Pink as a sad clown, as a TSA agent, working at Walmart, with a pet skunk, and on a field trip to D.C. (a scene referencing the January 6 U.S. capitol riot, where Pink was in attendance), his face often warped by the algorithm. Every cover bears the phrase “ARIEL STINKS” for its added “comedic potential,” per Miller.

Field Trip to DC, from the series “Ariel Stinks (50 Alternative Album Covers to Thrash and Burn).” Photo: Jill Miller.

The first part of Miller’s “Ariel Stinks” NFT series has been released on crypto art marketplace Taex in one-for-one editions, priced at 0.39 ETH (about $624) each; a second drop is planned for February 2. One cover has also been made available for free as a digital download.

“Making a series of NFTs felt like the right response to a 16-year-old album cover with my stolen image on it,” said Miller. “I wanted the series to exist in a form that resonated with 2023—which is digital music.” Buyers of the NFTs, too, will retain commercial rights to the work.

The medium of NFTs further befits an artist, also the Assistant Professor in Art Practice at the University of California, Berkeley, whose practice has been intertwined with new media. In her work, she has sought to challenge contemporary perceptions with the help of technologies from augmented reality to 3D rendering to the internet. Her foray into NFTs, she said, expands on those explorations.

“As an artist who experiments with new technologies, I was curious about NFTs existing as art without the physical object,” she explained. “I see them as being conceptually linked to early photography, video, and other art forms that confused (and later delighted) the art world.”

Ariel Stars in a Horror Film, from the series “Ariel Stinks (50 Alternative Album Covers to Thrash and Burn).” Photo: Jill Miller.

And A.I., for that matter, is “another tool in the artist’s box,” Miller said. “I think it could be used as part of a studio practice, but I don’t think it’s essential.”

For “Ariel Stinks,” she used a text-to-image generator to “imagine a number of ways that Ariel could literally stink,” before editing the output in post-production. A generated image featuring Pink on a For Wanted poster, for example, was reworked to include a quote from Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication on the Rights of Woman.

The technology, too, served as a mediating layer between artist and subject, according to Miller. “Making a portrait is quite an intimate exercise,” she said. “I used the A.I. to run interference between Ariel Pink and me… The A.I. acts as a buffer between us, so I don’t have to look too closely for too long.”

Miller is of course well-aware of the copyright litigation currently swirling generative A.I., and has covered her legal bases. According to her attorney, M.J. Bogatin, an intellectual property lawyer based in California, “Ariel Stinks” falls under the fair use exemption of U.S. copyright law, as the work would be considered parody. “She absolutely has the creative license to use Pink’s image, to adulterate it the way she has,” he told Billboard.

Ariel works at Walmart, from the series “Ariel Stinks (50 Alternative Album Covers to Thrash and Burn).” Photo: Jill Miller.

All 50 “Ariel Stinks” covers will be compiled and released as a coffee-table book, the culmination of Miller’s project to reclaim her image, while examining the bounds of appropriation. The act, she said, “calls into question outdated values or cultural assumptions.”

“The record preceded the #MeToo movement,” she added, “and back then men were still getting away with things that would not be allowed today.”

Grier, for his part, has apologized for “unwisely [choosing the photograph of Miller] as the cover art for the release.” Pink—who, January 6 aside, has long courted controversy by spouting statements that have been deemed racist and misogynist—called the project “a prank” and “a sort of snarky bit of revenge,” adding that it exists “to make me look bad.”

“I didn’t realize he called it a prank!” said Miller about Pink’s response. “That’s funny, but not surprising. He can’t really acknowledge it as art without accepting the underlying concept behind it, which is that he authorized his record label to use my image without my permission.”