Photo: @andrewesiebo/Instagram.

A work from the 2014 Welling Court Mural Project.

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

The Think Piece: As street art makes its way into more museums and auction houses, and neighbors fight to preserve illegal murals that would have been deemed blight 20 years ago, the Financial Times‘s Peter Aspden wonders whether the art form has lost its edge. “The battle is to take it back,” street artist and dealer Pure Evil (real name Charles Uzzell-Edwards) tells Aspden. Of course, the writer then visits Pure Evil’s eponymous gallery and describes his decidedly edge-less work thusly: “Warholesque prints of celebrities who are shedding trademark tears which often flow off the canvas all the way down to the floor.”

Ryann Ford, White Sands National Monument, New Mexico.

Photo: Ryann Ford, courtesy the artist.

The Eye Candy: The rest stops dotting US highways were once highly distinctive architectural markers of their specific location. But as rest stops have gone the way of the suburban mall food court, so these colorful relics of a bygone era of automotive tourism have begun to disappear. But not before a photographer with an appropriately car-based name, Ryann Ford, spent five years traveling the country photographing old-timey rest stops. The Wall Street Journal published selections from her resulting series, “The Last Stop.” Prints from the series are also available on her Etsy page.

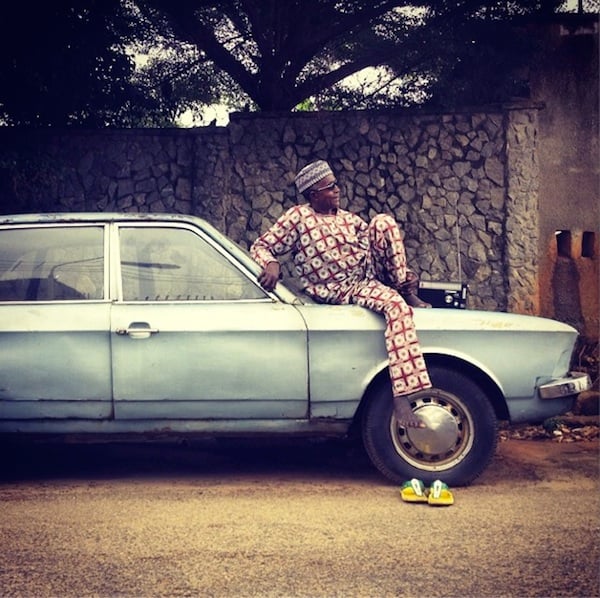

“Alhaji Umaru. Based in #lagos but very conscious of global politics and affairs. Thanks to his transistor #radio in which he gets globally in tuned. #lagos #andrewesiebo.”

Photo: @andrewesiebo/Instagram.

The Instagram User to Follow: Nigerian photographer Andrew Esiebo has been documenting his home city of Lagos for two years now on Instagram (@andrewesiebo), and is one of a group of photographers throughout Africa using social media in an attempt to give a better sense of everyday life on the continent. Their collective Instagram account, @EverydayAfrica, is a must-follow. “Instagram has been quite remarkable in the impact it’s had, especially in the northern hemisphere where people have little idea of everyday life here,” Esiebo tells the Guardian. “From a technical point of view it’s more limiting, but the idea of using Instagram for storytelling just makes a lot of sense.”

The Interview: Master forger John Myatt, who is currently having a solo show of his non-forgery artworks at London’s Castle Fine Art (see artnet News report), speaks with the Independent about his time in jail and how he made portraits of his fellow inmates to obtain contraband. “Money doesn’t get you anything in prison,” he says. “It’s a barter economy and the principal currencies were drugs and tobacco, but I didn’t do either. The only way I had of making money inside was doing prison portraits; I charged two phone cards for one pencil drawing, which was good money.”

Some middlebrow art currently on view at the Whitney Museum.

Photo: Benjamin Sutton.

The Extracurricular: New York Times film critic A.O. Scott is the latest writer to apply the ideas outlined by Thomas Piketty in his blockbuster tome of economic theory Capital in the 21st Century to the field of culture. For Scott, as the divide between lower- and upper-class grows, and the middle-class shrivels, it spells the end of middlebrow culture, which he sees as a potentially positive phenomenon. “In the hectic heyday of the middlebrow, intellectuals gazed back longingly at earlier dispensations when masterpieces were forged in conditions of inequality by lucky or well-born artists favored by rich or titled patrons,” Scott writes. “Social inequality may be returning, but that doesn’t mean that the masterpieces will follow. The highbrows were co-opted or killed off by the middle, and the elitism they championed has been replaced by another kind, the kind that measures all value, cultural and otherwise, in money.”