The opening of a new art season is usually filled with excitement and anticipation. But this year, there is also a nervous vibration in the air. Heading into the onslaught of competing events around the globe, market players are trying to shake off the lingering unease of a slow summer that marked two years of the broader slowdown in sales at galleries, fairs, and auctions.

The cooling of the Asian market, retreat of speculators, the Israel-Gaza war and conflict in Ukraine, stubbornly high interest rates, upcoming U.S. presidential election—these are some stress factors that are making art buyers and sellers nervous.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty everywhere and no market likes uncertainty,” said art dealer Allegra LaViola, who expanded during the downturn.

Still, there’s cautious optimism, momentum, and growth. Christie’s is set to open new headquarters in Hong Kong despite the contraction in Chinese buying and tightening of the government’s iron grip. It follows the launch of Sotheby’s Maison in the city in July. The two houses will host their first sales in the new sale rooms later this month. In October, the newly renamed Art Basel Paris will launch in a revamped Grand Palais.

The stakes are especially high this season, which opens with overlapping trade events, anchored by the Armory Show in New York and Frieze Seoul in South Korea. Major galleries and auction houses have laid off staff over the summer and began reviewing sales targets in the face of more sobering reality. At least two dozen galleries closed in New York in the past year. Many are barely hanging on and the next four months will determine their fate.

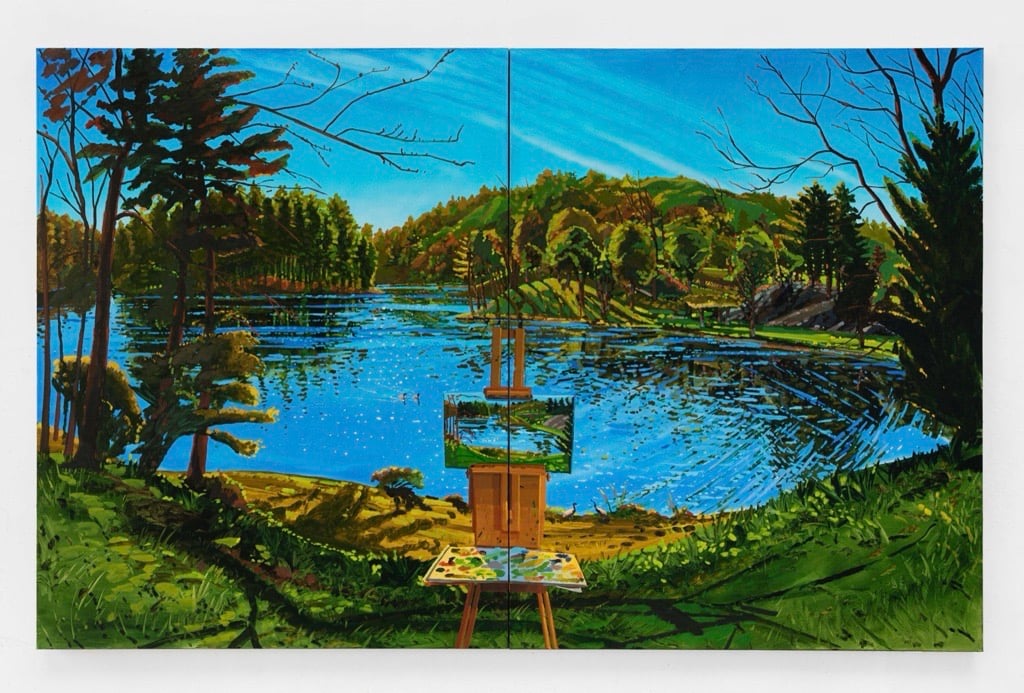

Courtesy of the Armory Show.

So far, just two big-name estates have been locked in for bellwether November auctions. In the aisles of the Javits Center, where the Armory Show brings together 235 exhibitors, secondary market dealers and advisers buzzed with the news yesterday: “Have you heard?” Apparently, Christie’s won the trove of the late interior designer Mica Ertegun, led by Rene Magritte’s masterpiece The Empire of Light while Sotheby’s got the collection of the late Palm Beach beauty mogul Sydell Miller, with its large, late water lilies by Claude Monet. The companies didn’t immediately respond to requests to comment.

Economic uncertainty or not, “great collectors are continuing to collect and are looking for beautiful things to live with,” an art advisor told me.

A downturn can be an opportunity. I was reminded of that during my recent visit to Glenstone, a private museum outside of Washington, D.C., whose jaw-dropping collection was largely built during the financial crisis of 2008.

Enthusiasm for art—and its sheer urgency in our lives—tends to blossom in tough times. The energy is palpable in New York this week, with many crowded openings and at least one sold out show: Hilary Pecis at David Kordansky where prices range from $125,000 to $225,000.

Hilary Pecis at David Kordanksy Gallery’s booth. Photo: Katya Kazakina

But sold-out shows are now an exception, not a rule. Artnet’s Andrew Russeth and Vivienne Chow reported slow sales at the VIP openings of Frieze Seoul and Kiaf Seoul. At the Armory Show, an art advisor told my colleague Eileen Kinsella that she was surprised when some works she wanted had been already placed.

Dealers are also adjusting to the changing conditions.

“Decoupling love of art and making a quick buck is necessary for the market,” said art dealer Harper Levine, founder of Harper’s Gallery.

Levine just closed his gallery in Los Angeles, after expanding aggressively during the pandemic. He still operates four spaces in Manhattan, one in East Hampton, and is eyeing an international location.

I stopped by his Chelsea gallery on the eve of the VIP opening of the Armory Show, in which Harper’s participates for the first time. “The worst is over, and things are getting better,” he said. As if to reinforce the positive vibes, the gallery’s group presentation featured ecstatic-looking paintings of plants, flowers, bubbles, bugs, and sunsets.

Installation shot of Harper’s booth at the Armory Show. Courtesy of Harper’s.

The following day, Levine texted me: “We’ve had a crazy day here at Armory, basically sold the whole booth.” The gallery placed 10-12 works, with prices ranging from $14,000 to $60,000, Levine said. Some were pre-sold, others took place at the fair.

“The market now has more clarity compared to the uncertainty that lingered over the summer,” said advisor and collector Adam Green. “There is broad acknowledgment among dealers, advisors, collectors, and even artists that the feeding frenzy of recent years is behind us, and we’ve entered a more normalized environment.”

Asya Geisberg, who moved her gallery to Tribeca from Chelsea this year, is another first-time Armory Show participant. Her stark booth featured solo presentation by Chilean artist Rodrigo Valenzuela, whose white ceramic pieces and photogravures depicting them gleamed on black walls. Prices ranged from $5,000 to $9,000. “I have faith that money will be made,” Geisberg said before the fair.

At the VIP opening, she spoke with so many people she almost lost her voice, but made no sales from the booth. Undeterred, she followed up with emails late into the night. On day two, she got a mention in Hyperallergic as “Most Duchampian” booth at the fair. By mid afternoon she had a confirmed sale: a museum trustee bought Valenzuela’s ceramic and a corresponding photo.

Rodrigo Valenzuela in Asya Geisberg Gallery booth at Armory Show 2024

The fair represented a serious investment for Geisberg, who operates a small gallery with idiosyncratic program. “It’s totally worth it,” she said. “This is my hometown. I believe in Rodrigo. I believe in the Armory. I have all the resources of being here in New York. It would be impossible for someone my size to do this if I had to go to a fair in Brussels or London. And you’ve got to take any advantage you have and go with it.”

Charles Moffett, who is returning to the Armory Show for the fourth time, pre-sold several landscapes by Keiran Brennan Hinton, priced at $5,000 to $30,000, as a safety net “to cover our bases, knowing that the market isn’t quite as frothy as it has been in the past,” he said. “Everyone in some shape or form is aware that it hasn’t been the same level of sales—whether it’s at a gallery or art fair.”

With FOMO, froth, and frenzy largely gone, buyers are in no rush to pull the trigger. There’s less competition. Access is easier. Waitlists for very in-demand artists still exist, but they are shorter than before.

“We definitely slowed down,” said Susan Hort, a consummate New York art collector if there was one. “Prices are too high, and we have a lot. I don’t want to buy and put things in storage.”

Installation view of Keiran Brennan Hinton solo show at Charles Moffett. Photo by Silvia Ros. Image courtesy the artist and Charles Moffett.

Green’s clients approach acquisitions “with greater selectivity, focusing on specific artists and high-quality examples of their work,” he said. Prices have to be right.

Dealers are discovering that they must work harder to get people’s attention.

“It’s taking more effort, more follow up, maybe not just one email, two emails, three emails just to get people to engage,” Moffett said. “Do I miss sending out a PDF and selling out the show off a PDF? Yes!”

Now that collectors have more time to make decisions, they try to see the art they are considering for acquisitions in the flesh, he said.

“There’s an interesting conversation that comes about when people place a work on reserve, have time to think about it, and actually come and see it,” said Moffett. “It’s a very positive reset.”

Reconnecting with art’s intrinsic value—as a cultural object, not a financial instrument—may be the ultimate silver lining of the new art season now that we’ve all awakened from the fever dream that was the pandemic art boom.