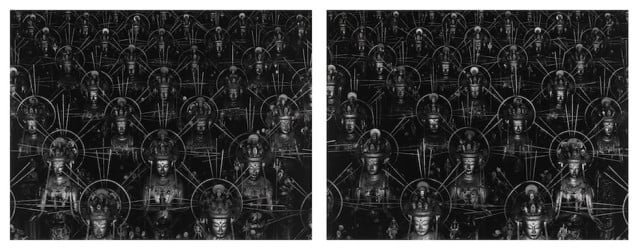

(Sea of Buddha 001, 002, 003 (detail); © Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy Pace Gallery, photo courtesy the artist)

THE DAILY PIC (#1496): I guess there’s an expectation that, as an art critic, each time I see a piece I’m supposed to come up with a new take on it. Well, to hell with that. I recently re-saw an installation of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Sea of Buddha at Pace Gallery in New York, just about 10 years to the day since I first confronted it in Sugimoto’s wonderful retrospective at the Hirshhorn museum in Washington. (Today’s Pic samples two of the series’s 48 photos.) A decade hasn’t left me all that much smarter, so here’s what I thought about it back then:

In a 12th-century temple in Kyoto, 1,001 gilded statues of the Buddha, sculpted almost at life size, face a translucent rice-paper shoji screen that fills a nearby temple wall. For a brief while in the early morning, according to Sugimoto’s account, the rising sun filters through that scrim, casting an unearthly glow over the sacred figures. (That glow reads as unearthly in part because it has no equivalent in nature. We hardly ever see it even in man-made settings: Sugimoto says he had to get special access to the temple’s morning light, before the monks came in at 9 to turn on the fluorescents.)

In 1995, Sugimoto set out to document those ranks of sculpted Buddhas, arranged nine-deep on low bleachers in a room-spanning row. Once again, he lugged his huge view camera in to do the job. The 48 crystal-clear pictures that came out of the shoot are mounted edge to edge, so they form a panoramic field of Buddhas that completely fill the picture space, just as the originals fill your eyes in Kyoto.

“Just as”? Maybe not. Sugimoto’s “truthful” depiction of these figures is in fact hugely artificial. To get such an improbably crisp focus across all the figures at the same time, he had to twist his lens and film in opposite directions — a trick you couldn’t try at home even if you wanted to, because it takes the most sophisticated photographic equipment and full knowledge of how its optics and mechanisms work.

To get his lens-filling, square-on view of all the Buddhas, he also had to shoot from a high vantage point, where no ordinary viewer would ever perch.

Finally, it turns out that Sugimoto’s truthful-looking panorama of the Buddhas shows us far, far more than the temple’s 1,001 sculptures. Because the Hirshhorn panorama is made by assembling a suite of separate photos, in which the camera was moved over to catch a new batch of Buddhas in each picture, only the frontmost sculptures actually change with every shot. Each time the camera moves sideways, many of the back-row Buddhas seen in one shot are repeated in the next. (Imagine standing at the back of a rock concert, looking at the two fans right in front of you. If you edge sideways so you’re staring instead at the next two over, the people in the far front row will mostly be the same ones you saw a moment before.)

One cliche about Buddhism is that it achieves its spiritual goals by encouraging the most intense, direct confrontation with reality — the here-and-now transcended by confronting the here-and-now. And yet Sugimoto’s photographs, which seem to capture such notions better than most others might, are about as full of unreality and trickery as anything could be.

You could argue that they use Madison Avenue lies to hint at spiritual truths.

And one new thought that comes to me in 2016: They are close kin to Warhol’s Campbell soups.

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.