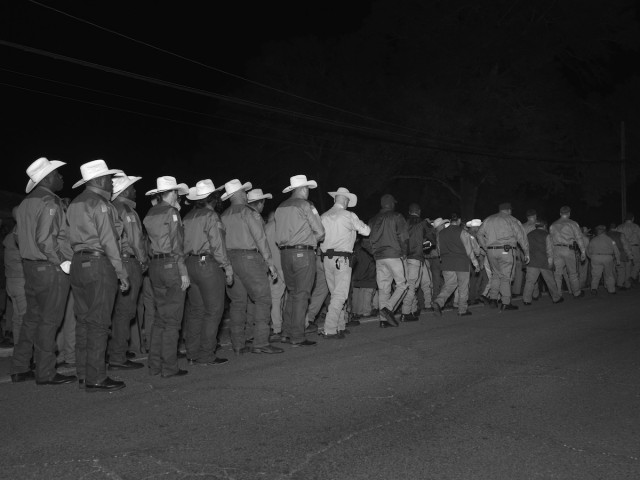

This is Execution, Huntsville Prison, Huntsville, Texas by Alec Soth, now on view at Sean Kelly gallery in New York. A while ago, I argued that Ansel Adams’s shots of unsullied nature where actually about the technology that first led to his making them, back before World War II. Soth’s latest photos made me revisit this idea. His pictures of odd corners of American life ought to seem like nothing more than another kick at the can of postwar street photography, so why have so many critics–including me–responded so strongly to them? I think the answer is that the preternatural sharpness and lack of grain in Soth’s huge black-and-white prints sets them off from the grainy look of traditional, 35mm, shoot-from-the-hip street photos. Instead, they evoke the older world of 19th-century view-camera work, with the special authority that comes from such a slow, formal take on the world – closer in some ways to the perspective constructions of Renaissance altarpieces than to the snapshots that Kodak brought about. The first images that made us notice Soth, early this century, were shot on giant 8-by-10 inch sheet film, and were quite clearly updates on that older tradition; they mostly involved today’s characters frozen in the fixed poses of yesteryear. The newer images at Sean Kelly were shot with a medium-format Hasselblad camera, giving Soth most of the flexibility of off-the-cuff 35mm work, but using an advanced digital back that gives the final prints their absurd, and archaic, view-camera clarity. Whatever their apparent subjects, Soth’s photos are about the authority that our new digital technologies give to our most casual views of reality. The whole world is now available to our eyes at a moment’s notice, all at once and in every detail. If Ansel Adams’s landscapes are about the new highways that gave him access to nature, then Soth’s new street photography is about the view from a cell phone, writ large. (©Alec Soth, courtesy Sean Kelly, New York)