Eleanor Xiniwe, The African Choir. London Stereoscopic Company (1891).

Courtesy of © Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

A collection of archival photographs (all taken prior to 1938) has surfaced as the result of a British research project called the Missing Chapter, which aims to “redress persistent ‘absence’ within the historical record.”

This ‘absence’ is the black subject in Victorian Britain, and Renée Mussai and Mark Sealy MBE, the curators of Black Chronicles II, are working with these archival photos to create visibility. The exhibition seeks to “open up critical inquiry into the archive and continue our mission of writing black photographic history. At the heart of the exhibition is the desire to resurrect black figures from oblivion and re-introduce them into contemporary consciousness.”

“They are here because you were there,” wrote cultural theorist Stuart Hall in 2008. “There is an umbilical connection. There is no understanding Englishness without understanding its imperial and colonial dimensions.” Hall’s “presence is palpable” throughout the exhibition, artnet News was told during an interview with Vera Grant, Executive Director of The Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African-American Art at the Hutchins Center, Harvard University. The acclaimed show, a collaboration with the Hulton Archive (a division of Getty Images), on view at Autograph ABP in London last year opened stateside on September 2.

The gallery, designed by famed architect David Adjaye, is conducive to “curatorial moments that meander,” says Grant, making it a particularly good space for viewers to encounter the narrative elements in the exhibition.

And while the photographs are powerful enough to need no textual accompaniments, the subjects’ backstories are fascinating and revealing — these explanations show how and why the sitters found themselves having their portraits taken in London. Some subjects were performers, athletes, dignitaries — members of groups that had “global mobility” and traveled to London freely. Though the darker side of colonial practices meant that others were servants to imperial elites. The London Stereoscopic Company captured them all.

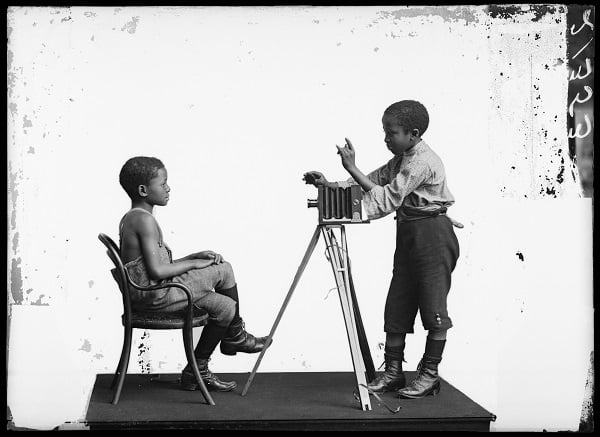

The elegant Eleanor Xiniwe traveled from South Africa with The African Choir to perform for British audiences. from 1891-1893, the troupe canvassed Britain to raise money for a technical college back home. Peter Jackson, a boxer from the Virgin Islands (then the Danish West Indies), donned his finest dress for his portrait. The “Black Prince” emigrated to Australia and won the heavyweight title in 1886, and received international recognition before his death in 1901. The young duo, Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe, were posed in a performance of photographer and sitter, replicating the postures they observed in the adults.

“Black Chronicles II” is atypical in that the research project that it emerges from isn’t finished yet: there is history yet to be uncovered. But Grant speaks of the exhibition as “a gift” that raises important and necessary implications that resonate strongly today: for the exhibition to be shared as work-in-progress communicates the necessity that these photographs be seen today.

Peter Jackson. London Stereoscopic Company, 2 December (1889).

Courtesy of © Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe, The African Choir. London Stereoscopic Company (1891).

Courtesy of © Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

“Black Chronicles II” will be on view from September 2 – December 11, 2015 at The Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African-American Art, Cambridge, MA.