As the world watches the Amazon disappear by the day, artists from the region are finally gaining recognition on the global stage. The most recent São Paulo bienal included five Indigenous artists—the most ever. Meanwhile, recent shows at the Pinacoteca and the Museu de Arte Moderna, both in São Paulo, have presented overviews of contemporary Indigenous art. And in New York, this year’s Armory Show highlights the work of several artists whose practices—and lives—have been shaped by the Amazon.

This increasing interest in the Amazon within the Brazilian art scene corresponds to a growing awareness of issues around Indigenous land rights and environmental protection in Brazil. Largely, this is because of how dire the situation has grown as president Jair Bolsonaro rolls back regulations.

According to a recent Forensic Architecture report, Bolsonaro has specifically “adopted policies to encourage gold mining on Indigenous land.” Some researchers are now anticipating increased violence and aggression in the coming weeks as Bolsonaro faces a potential loss in the election scheduled for October 2.

A work of Brazilian artist Jaider Esbell during the 34th Biennale of Sao Paulo, at Ibirapuera park, in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Nelson Almeida/AFP via Getty Images.

This year’s edition of the Armory Show brings a selection of works that weave layered stories around the history, ecology, and politics of the fragile rainforest and those who live there—from the self-taught painter and Amazon rubber tapper (one who extracts latex from rubber trees) Hélio Melo to Macuxi artist and activist Jaider Esbell, whose work was just starting to make waves when he tragically died last year at just 41.

In the fair’s Focus section, curated by Carla Acevedo-Yates of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, one and two-person presentations look at the ways in which the environment intersects with personal and global politics. The section includes works by Melo, who was active in the post-war period, working at the same as the Neoconcretists who have dominated Brazilian art history narratives.

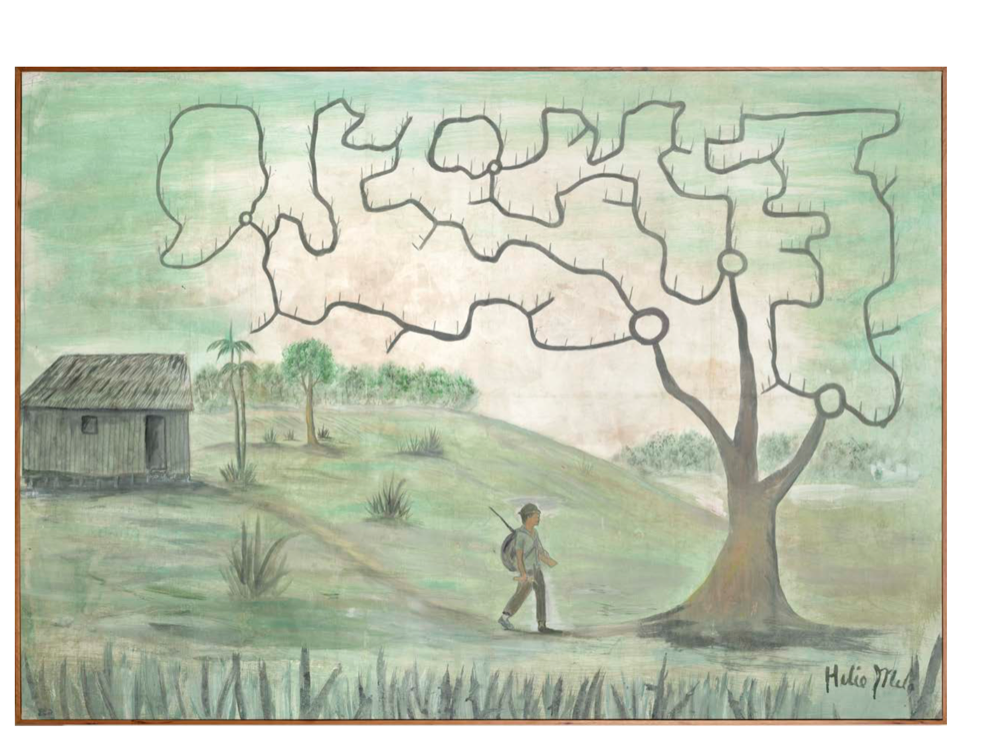

Melo’s polymathic practice included poetry, painting, and music. “He documents his life as a rubber tapper in the quotidian moments of cutting the tree, of a celebration, of a family having dinner,” said Paul Jenkins, director of the São Paulo gallery Almeida and Dale. “On top of that he layers this mysterious Amazonian universe with references to the myths and the customs of the forest, and delves into Surrealism.”

Hélio Melo, O homem e o burro (The Man and the Donkey) (1993). Courtesy Almeida and Dale.

Melo stopped tapping rubber at age 33 and later received moderate recognition for his work, showing it in galleries in the north of Brazil as well as in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, where he found a fan in Neoconcrete sculptor Sergio Camargo, who collected his work in depth. This week marks the first presentation of Melo’s work outside of Brazil since 1998, though his market is far from nascent with works on paper starting at $30,000 and larger canvases reaching $200,000.

Also in the Focus section, with Cecilia Brunson projects, is work by Katie van Scherpenberg, who was born in Brazil in 1940 and spent her childhood between Europe, Brazil, and North America before finding her way to the remote Amazonian island of Santana in 1968, living and working there for almost two decades. Her expansive practice is rooted in painting—she studied with Oskar Kokoschka in Europe—and her landscapes seem to have an almost psychological depth to them.

However, it is van Scherpenberg’s relationship to the Amazon River itself that has been the generative force in her practice, both for the pigments that it carries—which became her primary material—and for what it symbolizes about time, impermanence, and the relationship between human and nature.

Katie van Scherpenberg, Portal (1999). Courtesy of the artist and Cecilia Brunson Projects.

Van Scherpenberg had her first exhibition with Cecilia Brunson in 2021 and her showing this week indicates that her star is still rising at 82 years old, with smaller works available for less than $10,000 and larger paintings topping out around $60,000.

Peruvian artist Roberto Huarcaya’s large-scale photograms, taken in the Bahajua Sonene Natural Reserve in the Peruvian Amazon (at the invitation of the Wildlife Conservation Society), are on view in the Platform section of the fair. The section, curated by Tobias Ostrander from Tate London, takes on the timely matter of monuments: what we have chosen to memorialize and how we may choose differently into the future.

Huarcaya’s massive works, which he calls “Amazogramas,” were made by suspending rolls of photosensitive paper throughout the jungle and using the moon, in part, for light. Huarcaya then used water from a local river to develop the images, which measure more than 1,000 inches in length—making the impression of leaves and foliage true to size. The Amazon is roughly equal in size to the land mass of the entire United States, yet the rate at which it is being deforested (the highest rate of burning in 15 years was recorded just a few weeks ago) means that considering ways to memorialize it may be coming sooner than we realize, giving Huarcaya’s works a weight far beyond their already domineering heft.

Installation view, Roberto Huarcaya, “Amazogramas, Casa Rimac” (2014). Courtesy of Rolf Art.

The largest of Huarcaya’s photograms are $160,000, while smaller works—unique pieces and editions—can be had for as little as $3,000.

In the main section of the fair, on view with São Paulo’s Millan gallery, is a selection of works ranging from $20,000 to $80,000 by Jaider Esbell, the indigenous Macuxi artist and activist whose intricately crafted paintings and sculptures were on the cusp of global recognition when the artist tragically died by suicide in November 2021.

Working in drawing, paper, video, performance, and text, Esbell’s practice was equal parts art and activism—a sharing and celebration of Indigenous cosmologies as a way to bridge worlds and thinking—which he termed “artivism.”

Jaider Esbell, Água, da série Elementais, (2018). Courtesy of Millan.

The past several years have seen Brazilian curators and art historians actively working to expand the hegemonic history of Brazilian art that has denied the contributions of Black and Indigenous artists, as well as anyone else outside of the middle and upper-middle classes. Yet it’s hard to imagine any of it without Esbell.

“Esbell was a driving force and leader of Brazil’s contemporary Indigenous art movement, always claiming the protagonism of Indigenous voices,” said Hena Lee of Millan gallery. “He was the first indigenous artist in Brazil to have a prominent presence in the center of discussions in the academy and institutions.”

Esbell’s presence in São Paulo was groundbreaking and while his legacy is still taking shape, it is clear already that it will be profound and long lasting.