Asked how their business is doing this spring compared to one year ago, the dealers Dominique Lévy and Brett Gorvy looked puzzled. They rejected the premise of the question. “You have to compare apples to apples,” Gorvy said.

We were speaking over Zoom—a far cry from 2019, when we crossed paths during Art Basel Hong Kong, where the dealing duo was opening a new gallery and making multi-million-dollar sales. This year, Lévy said, “the world is a different place. We’re in black and white circumstances.”

Like other galleries, Lévy Gorvy has swapped expos in metropolises around the world for online viewing rooms and digital fair platforms. And while the wave of innovation and collaboration this era has ushered in is all well and good, the question remains: Did any of the world’s top galleries, auction houses, and art advisors really sell any serious contemporary art during the first month of lockdown?

After talking with more than a dozen market players, a picture emerged of once-global elite now working from home (or, often, their second home), spending the days adapting to a new reality. Yes, some things are selling, but with the entire in-person infrastructure placed on hold, the volume of what’s trading hands is a fraction of a fraction of what it was a year ago—and only a narrow segment of the market is reliably active.

The conversations reveal that, for all its emphasis on online bells and whistles, the art market remains, at its heart, an in-person enterprise.

The interface for the online version of the Dallas Art Fair, which launched Tuesday. Photo courtesy Dallas Art Fair.

Speculated-upon superstars who, until last month, minted canvases as currency have seen their markets get a haircut overnight. Paintings that could flip for $500,000 two months ago suddenly can’t find homes for $200,000. One advisor who brokers deals primarily for high-end clients looking for expensive secondary-market works said that they were “literally selling nothing.”

“There’s just no secondary market right now, unless it’s at discounted, distressed, or very reasonable prices,” another advisor said.

On the primary market, collectors are still going after work in the $40,000 to $70,000 range, but primary-market deals inked last month rarely topped the $100,000 threshold. “The only regular business I’ve done is in-demand primary artists under $100,000,” another advisor said. “I did one a day last week. During a normal busy time, that’s not a lot of business.”

Smaller Numbers, Little by Little

At the start of the lockdown—just a calendar month ago, but what for some feels like an eternity of chaos—things seemed somewhat optimistic. After a month and a half of buildout, Art Basel Hong Kong’s online edition opened on March 18 with 235 galleries and a total of $270 million worth of art.

There, mega-galleries achieved something that was once commonplace, and is now a unicorn: the seven-figure sale. David Zwirner sold a painting by Marlene Dumas for $2.6 million and a painting by Luc Tuymans for $2 million, while Gagosian sold a Georg Baselitz for nearly $1.3 million.

But in the weeks that followed, the very real danger of the virus began to set in. “The people who we were reaching out to, that conversation was not about buying pictures, it was about friendships, and saying, ‘Are you OK?'” Gorvy said.

One advisor said that they were using the time to write long letters to their clients, telling them to seize the moment to research new artists—not necessarily to convince them to pull the trigger on anything.

As March turned to April, some advisors did tastefully bring up acquiring contemporary art—but it’s been a decidedly mellow period for transactions. Advisor Lisa Schiff said she sold just two works above $100,000, and instead focused on what would usually be considered—for an advisor with offices in Tribeca and Hollywood, and a client list that has included Robert de Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio and Meg Ryan—on the lower end of things. On the secondary market, Schiff mentioned that she had negotiated the purchase of a relatively inexpensive Sherrie Levine drawing.

“It’s just a different approach,” Schiff said. “Things are selling, we’re doing some primary market, and we did more secondary stuff mostly in smaller numbers, little by little.”

Harold Ancart’s Untitled (2020) which sold for $40,000 in the David Zwirner viewing room. Photo courtesy David Zwirner.

What’s Actually Selling

The primary market continues to churn, particularly for work by artists who were in high demand before the crisis hit. That’s bad news for long-suffering clients seeking an opportunity to leapfrog a waitlist, but good news for anyone hoping for signs of confidence in the market. “I still can’t get an Njideka Akunyili Crosby primary for my best clients,” Schiff said.

Among the more sought-after figures right now, according to another advisor, are Asuka Anastacia Ogawa (whose solo show at Blum & Poe’s Tokyo space was set to make a splash this spring before getting postponed), Jennifer Guidi, and Shara Hughes. Hauser & Wirth sold out of its viewing-room presentation of drawings by George Condo, priced at $125,000 (with 10 percent of the sales going to COVID-19 relief efforts) and Zwirner sold out of its virtual presentation of Harold Ancart’s new pool works, priced at $40,000 apiece.

There is also an understanding that low supply can help with what may be lower demand. While it also has online viewing rooms galore, the Artist Spotlight program at Gagosian makes available just one work each week, and last Friday a new work by Sarah Sze sold for $250,000.

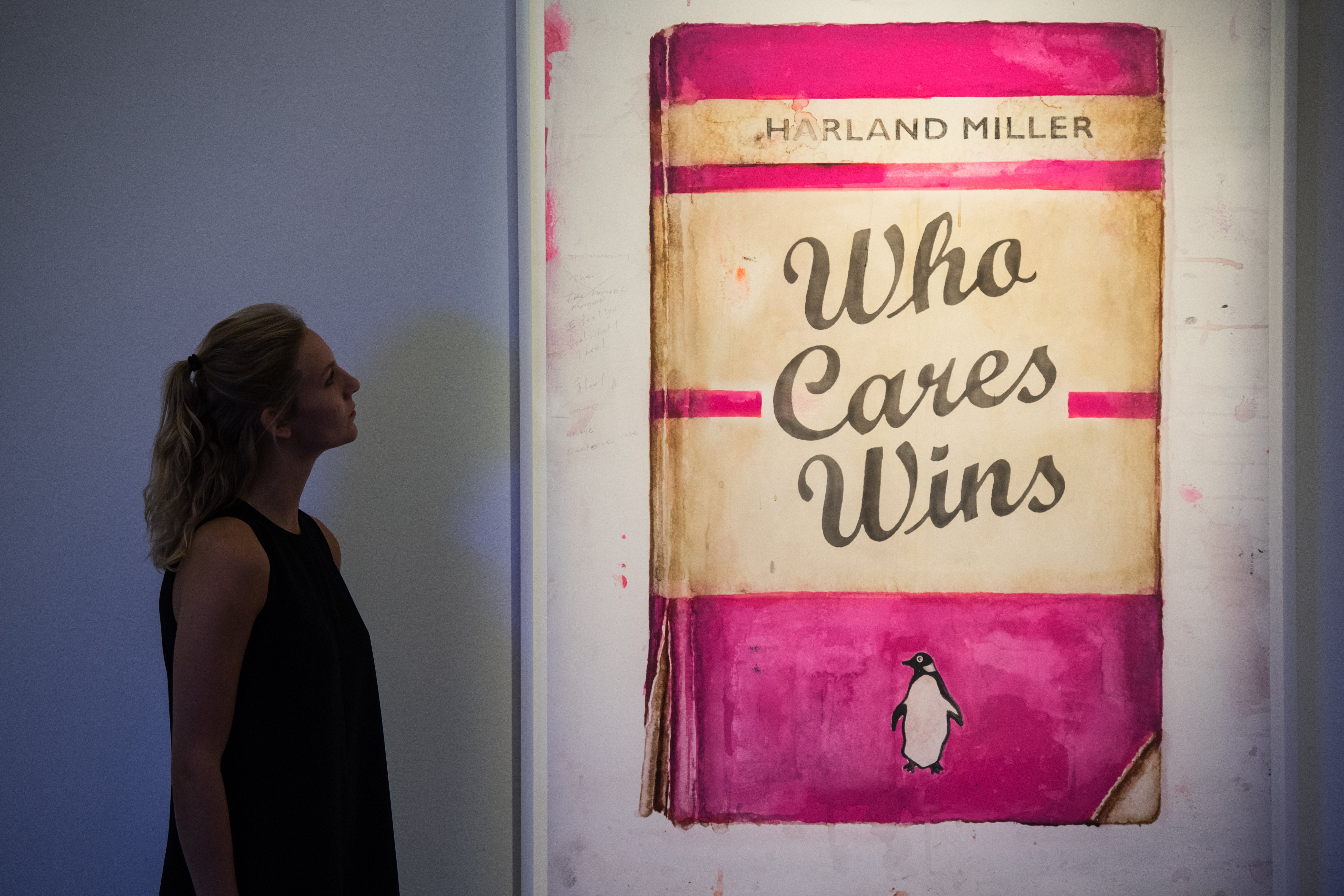

Some galleries, meanwhile, are taking the opposite approach, and releasing editions in high numbers priced low in order to crowdsource the buying. White Cube released 250 editions of a new work by Harland Miller priced at £5,000 and they all sold in 24 hours—all of the £1.25 million raised going to a number of causes tackling the pandemic.

And other galleries are having luck selling more established artists well past mid-career status. Lévy Gorvy sold a work from its online show of Chinese artist Tu Hongtao and another from a viewing room by the centenarian French artist Pierre Soulages—who was born not long after the Spanish flu pandemic. It sold for somewhere in the range of $870,000 and $1.3 million.

One way to restart the market, on both the primary and the secondary sides, is to entice buyers with slashed prices. While some speculators are unwilling to part with what were once ready-to-flip works at a loss, some dealers are already offering eye-popping discounts.

“A mid-level New York gallery just sent an email saying that, for the month of April, it’s 30 percent off everything,” an advisor said. “It’s crazy. It’s like Net-a-porter.”

László Moholy-Nagy, ‘UMSCHLAG FÜR DIE ZEITSCHRIFT “BROOM”’ (PHOTOGRAM ‘COVER FOR THE MAGAZINE “BROOM”‘) which sold at Sotheby’s earlier this month. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

The Last £30 Million Sale?

With all the real-life salesroom action on hold for the time being—and many expecting the June sales to be postponed as well, or at least reimagined in a radically social-distance-y way—major auction houses have, like their gallery peers, turned to the great salesroom in the cloud. The performance of online auctions has been somewhat middling, with the highlight being a László Moholy-Nagy work that sold in a Sotheby’s photo sale for $524,000—still below its high estimate.

The real action, however, is happening in private sales, according to the auction-house duopoly of Christie’s and Sotheby’s. (Phillips just launched its private sales portal—er, its online viewing room—this week, and does not have sales details yet.) This shift makes sense, since the total number of auctions held around the world and the number of lots sold dropped by 25 percent in March 2020 compared to the same month the previous year, according to the Artnet Price Database—and some of that squeezed-out activity needed a place to go.

At Sotheby’s, private sales went up immediately as the crisis was hitting, and department head David Schrader said that they have closed 30 deals in the last two weeks. “As is not uncommon during times of economic uncertainty, our conversations and negotiations with clients around private sales have increased significantly since the beginning of March, regarding both buying and selling works,” Schrader said in an email. “We are seeing significant appetite to transact right now, particularly when the best objects are available. Interestingly, we are seeing more demand from buyers than sellers at the moment.”

Meanwhile, sources within Christie’s say that private sales are up 27 percent compared to the first quarter of 2019. And according to a spokesperson, one deal brokered by the auction house had the gobsmacking price tag of £30 million—which means it resulted in a £4.05 million buyer’s premium for the house, likely more than perhaps any other sale, across all platforms, in the past month.

Who, and what, is actually driving the demand? There’s word that Asian buyers from countries that have relatively stabilized economies have been very active in private sales at Christie’s. And, separately, sources said that some transactions are actually coming out of all the time employees are putting in to beef up online content. One collector is said to have discovered a work from an article in Christie’s content section that went up a few days ago, took a fancy to it, and bought it from the website. (Christie’s would not specify which, but the auction house recently published a story about the Jean-Michel Basquiat drawing Untitled (Dynamic Tension), which was previously in the collection of Andy Warhol.)

Installation view, Tu Hongtao, Lévy Gorvy Hong Kong, 2020. Photo: Kitmin Lee. Photo courtesy Levy Gorvy.

Twice the Hard Work for a Quarter of the Real Business

Regardless of how many transactions are initiated this season, the true test will be whether money actually manages to change hands. A number of sales, particularly those priced in the seven figures, are currently on hold. “If you’re spending millions of dollars, you want to see the work, and it’s hard logistically to show it,” Schiff said.

Any success will be hard-won. A source on the online content side of a mega-gallery said that they have been working late in the night in order to put together new viewing rooms for exhibitions. And independent dealers and advisors are also burning the midnight oil to keep their businesses afloat.

“You have to work twice as hard to get a quarter of the business done, but it’s worth it, and it’s crucial to keeping our businesses alive,” said the advisor Meredith Darrow. “I didn’t sign up for a desk job, but that’s what I have now. I’m at my desk from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. every day. It’s boring and it’s laborious, but there is something gratifying about it, and at the end I’ll come out a better dealer.”

Brett Gorvy is also aware that such transactions often require in-the-flesh confirmation before cutting a check; the client who bought the Soulages, for example, saw the painting with their own eyes before the gallery closed. One solution some dealers are trying? Making appointments for collectors to see the work in the real gallery, in a really private viewing room, as long as all social-distancing measures are followed.

“The most challenging aspect is, how do you get in front of the work itself?” Gorvy said. “We’re trying to get people into a completely empty and clean safe space, if that is feasible. We’re talking about incredible challenges, but there are people who are willing to do this.”