Courtesy Christie's.

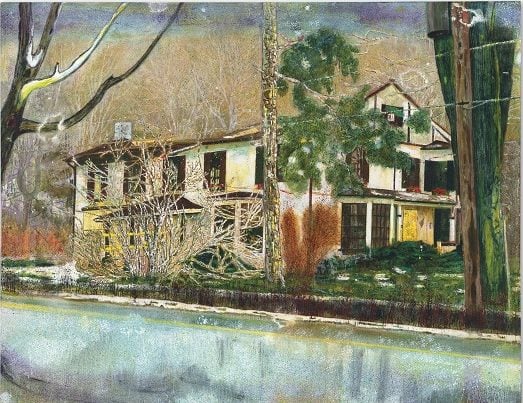

The art market continued its upward climb last week with unprecedented results at the New York auctions. But when Jasper Johns’s Flag (1983) makes a record $36 million at Sotheby’s (see “Rothko Reels In $45 Million at Sotheby’s $343.6 Million Contemporary Evening Sale“) or Peter Doig’s Pine House (Rooms for Rent) (1994) fetches $18 million (also a record), at Christie’s (see “Epic Christie’s $852.9 Million Blockbuster Contemporary Art Sale Is the Highest Ever“), it may not necessarily be good news for all. In a recent interview with German magazine Monopol, Allianz’s art insurance chief Georg von Gumppenberg suggests that the ever-rising art market is putting a damper on the quality of art most museums are able to show.

“Why?” you may ask. The answer is: insurance costs. Von Gumppenberg explains that pieces or groups of works that were in the past insured for one million may now be worth two to five times that amount. Thus, when museums want to own or borrow such works for an exhibition, they have to pay insurance premiums that are essentially two to five times the amount they would have had to pay in the past.

Doig is a particularly good example of the shift. The Christie’s result last week makes him the most expensive living artist from the UK. But even a half-decade ago, his prices were nowhere near as high (see “Peter Doig: Anatomy of an Art World Phenomenon“). Pine House (Rooms for Rent) (1994) sold for just $2.3 million when it last hit the auction block at Christie’s London in 2009. So, taking von Gumppenberg’s given premium calculation at two per mil as an example, premiums on the work have in just five years risen from $4,600 to $26,000.

According to the insurance expert, such increases mean that an ever-increasing number of museums are unable to afford exhibitions of high quality or popular artists on their own. He says that “museum directors must always be resourceful in obtaining external funding.” That may have long been the normal modus operandi for US institutions, but, on the continent, it is a relatively recent and difficult shift. So-called friends groups support European museums with various exhibition costs, but their funding only goes so far.

Collections are also affected. “Big acquisitions are no longer possible” for European institutions that rely on the state, von Gumppenberg adds.

That could mean a rather middling offering for the viewing public. When a major institution like Cologne’s Museum Ludwig announces that it needs €1.33 million essentially to keep the lights on due to energy and building maintenance cost increases, it’s not hard to imagine exhibitions suffering from insurance cost increases of a much greater multiple.