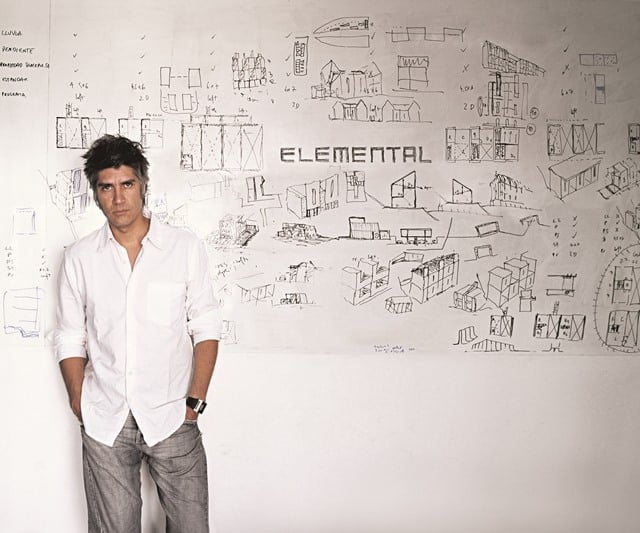

Photo: Cristobal Palma, courtesy Hyatt Foundation.

By their very nature, prizes are subjective—and flawed. In the past few weeks, for instance, magazines and newspapers were quick to note this year’s absence of black actors on the Oscar shortlist. And at the Grammy Awards earlier this month, Taylor Swift’s sleek 1989 confection laced with teen feminism depressingly beat out Kendrick Lamar’s epic, impactful tour de force “To Pimp a Butterfly” for Album of the Year.

In the more sedate world of design there is only one award that matters — the Pritzker Architecture Prize, which has had its own share of controversy over the years. Only two women have been bestowed the honor since it was founded in 1978: Zaha Hadid in 2004 and SANAA’s Kazuyo Sejima in 2010 (with Ryue Nishizawa). When Robert Venturi won in 1991, his wife and equal partner Denise Scott Brown had to make do with a single mention in the jury citation.

In 2013, two female students from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design gathered more than 20,000 names in an online petition to overturn the patriarchal move, to no avail. Not unlike the Oscars for Best Director, the Pritzker Prize has been partial to white men over sixty.

MIAMI BEACH, FL – MAY 15: (L-R) Alejandro Aravena, Jean Nouvel, Glenn Murcutt and Lord Peter Palumbo during Pritzker Architecture Prize 2015 at New World Symphony on May 15, 2015 in Miami Beach, Florida.

Photo by John Parra/Getty Images for Pritzker Architecture Prize.

So eyebrows were arched when 48-year-old Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena was announced the winner of the 41st Pritzker Prize in January. Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Hawthorne wrote, “Pritzker watchers looking for clues about potential winners perhaps needn’t have looked any further than the news that he left the jury last year.” At the Dallas Morning News, Mark Lamster added, “That timing inevitably, and unfortunately, raises the question as to the credibility of the $100,000 prize. But it is more generally indicative of the Pritzker’s historic inability to get out of its own way.”

In recent years, the Pritzker Prize has passed over several prominent senior architects in favor of younger ones engaged with contemporary issues. In what could be characterized as a mid-life crisis to reinvent their stodgy identity and a desire to broaden their audience, Wang Shu, 2012’s winner, represents the importance of China in the era of global urbanization while 2014’s Tokyo-born Shigeru Ban is an activist engaged in low-cost, recyclable shelters for disaster victims.

It’s in this quest for relevancy that the Pritzker powers that be shine the spotlight on their former juror. Aravena’s practice embodies many attractive buzzwords in architectural circles and academia: collaborative solution, social housing, innovation, civil society and individual responsibility. He is the opposite of spectacle architecture that has dominated the airwaves for the past two decades and slowly the pendulum swings to a new frontier. This past summer, he was appointed director of the 15th Venice Architecture Biennale, which was last held by Pritzker Prize winner starchitect Rem Koolhaas.

As art and architecture alternate in the Venice Biennales, the latter has always lacked the glamour, power and budget of its sister program, which is an ecosystem of artists, collectors, gallery and auction players, and of the museum world. It’s a perfect storm to see art, do business, and party. In contrast, the architecture biennales can be intimidating and technical, given the curatorial obstacles of making compelling exhibitions through drawings and scale models that are once removed from the actual project/space/building and thus result in a smaller audience.

In what could be posited as a provocation, Aravena announced his exhibition “Reporting From the Front” will tackle issues including segregation, inequality, access to sanitation, natural disasters, housing shortages, migration, crime, traffic, pollution, and the participation of local communities. The 88 participants hail from 37 different countries; over half are first-timers, and 33 are under the age of 40. It’s a refreshing proposition to see a generation of younger architects chosen to present innovative new work.

“They are battles that need to be fought,” Aravena charges in his Biennale introduction. “The forces that shape the built environment are not necessarily amicable either: the greed and impatience of capital or the single mindedness and conservatism of the bureaucracy tend to produce banal, mediocre and dull built environments.” He continues, “These are the frontlines from which we would like different practitioners to report, sharing success stories and exemplary cases where architecture did, is and will make a difference.”

As Aravena marches on to the opening of his exhibition on May 28, he’s emboldened by the new armor of the Pritzker Prize, which he will receive on April 4th at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Be it collusion or good luck, this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale and the Pritzker Prize are reflecting in each other’s seemingly quixotic decision: to bet big on an architect who just may have the right combination of idealism and pragmatism to drag us out of the 20th century and into a just new world.

Karen Wong was Managing Director of Adjaye Associates from 2000-2006. She is currently the Deputy Director of the New Museum.