Given the financial guarantees Sotheby’s needed to secure the huge cache of art collected by its former chairman, A. Alfred Taubman, who died in April, the New York company has yet to earn revenue or profit from auctioning it, the auction house said on Monday. Preparing for the Taubman sales, which kicked off November 4 with the best of the collection (which ranges from Old Master paintings to contemporary work), may also have distracted staff from a once-promising growth area: privately brokered transactions.

Private sales in the three months ending September 30 plunged 45 percent to $85 million, according to a filing Monday with the Securities and Exchange Commission. It was the auctioneer’s lowest tally since the third quarter of 2011.

The drop in the volatile category wasn’t an aberration. While second quarter private sales soared 59 percent, they rose just two percent for the first nine months. Last year, Sotheby’s private sales were the worst since 2010.

“We have a plan for improving our private sales execution that will be implemented for next year,” Sotheby’s chief executive of seven months, Tad Smith, said in a conference call Monday morning with analysts. “For competitive reasons, I don’t want to say much more about this, but there are many more things to come.”

Sotheby’s annual private sales peaked at $1.2 billion in 2013, under then-CEO William Ruprecht. (Ruprecht announced his resignation a year ago following pressure from activist investors frustrated by the depressed share price and earnings.) The $88 million in commissions from the 2013 private sales accounted for 10 percent of total revenue, as sellers enjoyed the discretion and relative safety of having their art shopped around quietly.

But private sales suffered of late amid the red hot auction market. As consignors have come to expect big prices in the salesroom—and big price guarantees from auctioneers seeking top material—there’s been less incentive to enlist the houses to sell privately.

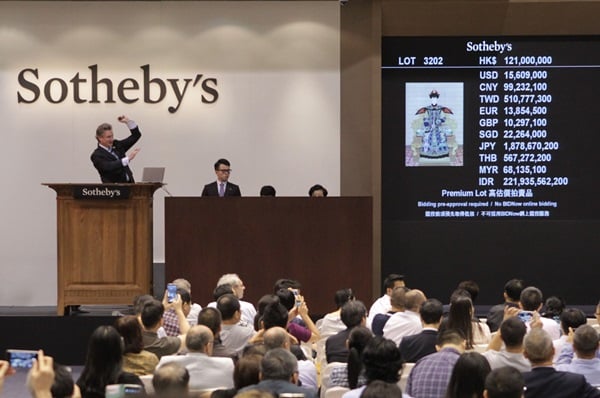

Last quarter, there was an added hurdle: Sotheby’s staffers were working on the four Taubman auctions, which the company guaranteed for $515 million. (In a guarantee, the auctioneer promises a minimum price for a work and is generally entitled to a share of proceeds above that price. If it goes unsold at auction, Sotheby’s takes possession and tries to resell it.)

“They had to be so focused on Taubman,” said Stephane Connery, an independent art advisor and former Sotheby’s worldwide head of private sales. “It was all hands on deck.” A Sotheby’s spokeswoman didn’t return e-mails for comment.

In Monday’s filing, Sotheby’s said it won’t earn anything from the Taubman auctions unless proceeds, including disposing of works that go unsold, exceed $515 million. Todd Levin, director of the Levin Art Group, said the company had to win the collection of its former chairman to save face, no matter how unfavorable the economics. “The best case scenario was to come out slightly bruised,” Levin said. Sotheby’s would’ve been “emasculated” had rival Christie’s won the consignment, he said.

Connery said he believes private sales will rebound as demand at auctions softens. “There is definitely a cooling in the market,” he said, citing in part the relative bargain price that Vincent van Gogh’s stately landscape Paysage Sous un Ciel Movemente fetched last week at Sotheby’s Impressionist and modern auction. It went for $54 million, well below the $70 million high estimate.

Connery said there’s less chance an artwork is stigmatized, or “burnt,” when shopped privately. “It takes the element of uncertainty out of it,” he said.

As of midday Tuesday, Sotheby’s shares tumbled 13 percent this week to a three-year low. Auction commission margins for the first nine months of 2015 were 15.3 percent, down from as high as 18.3 percent in 2010. Smith warned that expenses promoting the Taubman auctions will reduce auction margins for the fourth quarter.

Sotheby’s “has an approved strategic plan with the board” for creating a “compelling growth strategy,” Smith said. Without elaborating, he explained it’s made changes in how it secures consignments, how it hedges financial guarantees it extends and how it’s increased internal collaboration.

With competition with Christie’s as intense as ever at the top, and with the so-called auction middle market “more sluggish” than Sotheby’s would like (in Smith’s words), there are no easy answers to ending the auctioneer’s private—and very public—slump.