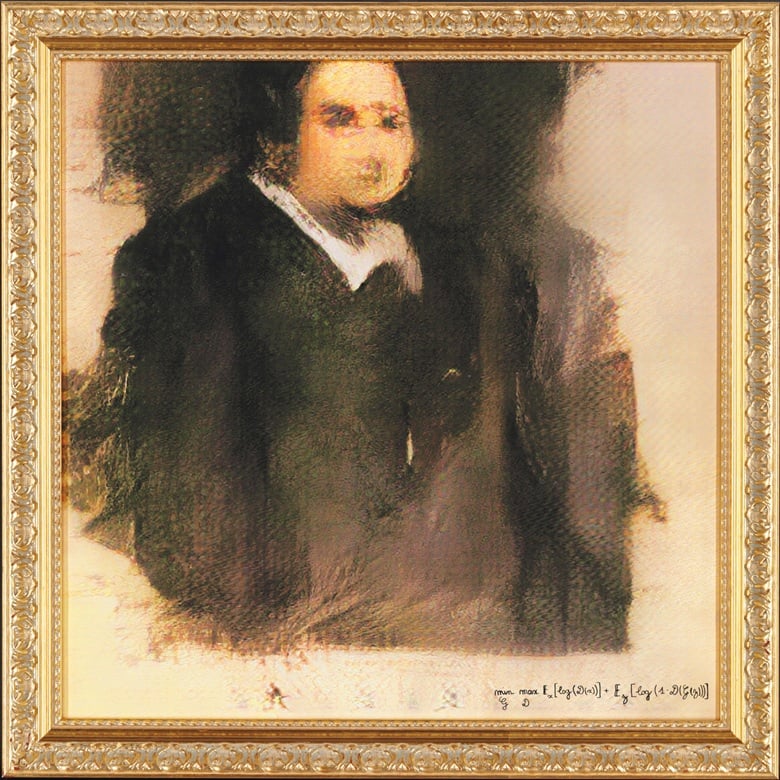

The first-ever work original work of art created using artificial intelligence to come to auction, Portrait of Edmond de Belamy (2018), smashed expectations at Christie’s New York this morning when it was hammered down for $350,000 after a lively bidding war that lasted for more than six minutes.

The final price, with premium, was $432,500—a whopping 4,320 percent increase from the presale high estimate of $10,000. Intense competition from bidders over the phone, in the room, and online swiftly drove the work over its $7,000 to $10,000 estimate. The action only began to slow after the price exceeded $200,000. An anonymous phone bidder won the lot after a battle between two phone bidders, an online participant in France, and one man in the room.

According to Christie’s catalogue description, the painting—”if that is the right term”—is one of a group of portraits of the fictional Belamy family created by an AI trained by Obvious, a Paris-based collective. Its members—Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel, and Gauthier Vernier—explore the fields of art and artificial intelligence using a set of algorithms that goes by the acronym GAN, which stands for “generative adversarial network.”

Co-founders of Obvious; Pierre Fautrel, Gauthier Vernier, and Hugo Caselles-Dupré. Courtesy of Ovious.

According to Caselles-Dupré, the algorithm used to create the work is composed of two parts: “On one side is the Generator, on the other the Discriminator,” he explained in Christie’s description of the lot. “We fed the system with a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th century to the 20th. The Generator makes a new image based on the set, then the Discriminator tries to spot the difference between a human-made image and one created by the Generator. The aim is to fool the Discriminator into thinking that the new images are real-life portraits. Then we have a result.”

The AI-generated work was the final lot in a prints and multiples sale at Christie’s New York that included works by Jeff Koons, Banksy, and Christo. The Obvious work was the second most expensive lot in the sale; the top lot was Andy Warhol’s suite of 10 screenprints, Myths (1981), which sold for $780,500.

Perusing the sale beforehand, curious observers might have realized something was afoot. The AI lot is the only one that doesn’t have an artist listed. Instead, the medium for the Belamy portrait is listed as “generative Adversarial Network print, on canvas, 2018, signed with GAN model loss function in ink by the publisher, from a series of eleven unique images, published by Obvious Art, Paris, with original gilded wood frame.”

The head of the prints and multiples department told The Art Newspaper that he is hardly an AI expert—in fact, he only learned about Obvious after reading an article on artnet News about a collector’s purchase of one of their works for around €10,000 ($12,000). (Considering the latest price, that somehow seems like a bargain.)

But Obvious has also attracted its fair share of critics, who contend that the hype about what AI technology can do on its own is premature—and that the current interest is driven more by speculation and novelty than deep engagement.

“People have been working with low resolution GANs like this since 2015,” Robbie Barrat, a young artist who works with AI, recently told artnet News. Barrat adds that last year, when he was 17 years old, he did a project using the exact same type of neural network and an identical data set. “No one in the AI and art sphere really considers them to be artists—they’re more like marketers,” he said.