Like so many other major art events planned for this spring, Frieze was forced to call off its New York fair—scheduled to be held in early May on Randall’s Island in Manhattan—due to the global health situation. But instead of going dark for 2020, the event is offering participating galleries the chance to show their wares online instead.

Next month, Frieze New York’s organizers will launch a virtual fair, allowing galleries the chance to have their own individual viewing rooms (think: art fair booths under a big tent), where they can showcase up to 30 works each. The site is also using augmented reality technology to offer users the ability to virtually view artworks to scale on their own walls. Plus, it will host video tours from curators of the fair’s special sections, including a special tribute to Chicago artists and a look at overlooked figures from the 20th century.

The virtual fair will debut on the same day the IRL fair was originally scheduled to open, kicking off with a VIP preview from May 6 though 7, but it will remain live a bit longer, through May 15. Like the in-person fair, it is sponsored by Deutsche Bank. “This is really similar to what the fair’s presentation would have been, just not in physical form now,” Loring Randolph, the director of Frieze New York, tells Artnet News.

Frieze’s viewing-room ambitions considerably predate the lockdown era. Randolph said the fair first began considering it a few years ago, when some of the bigger galleries—Gagosian, David Zwirner—launched their own individual platforms. Frieze sought to lower the barrier of entry for smaller and midsize galleries, which do not have the same development budgets as their behemoth peers. Of the more than 200 exhibitors at Frieze New York, the fair recently found that roughly 83 percent didn’t have their own dedicated viewing rooms, which allow galleries to more efficiently field offers for artworks.

“We saw an opportunity to make a platform available to a much wider group of galleries,” Randolph says. “And of course one of the things that fairs do that I think is a benefit, is bring everybody together under one roof in one place, so we thought we could do that through a digital platform.” Viewing rooms, she says, also offer dealers the opportunity to show projects that might not make sense at a physical fair—like a creative solo project, perhaps, or a video.

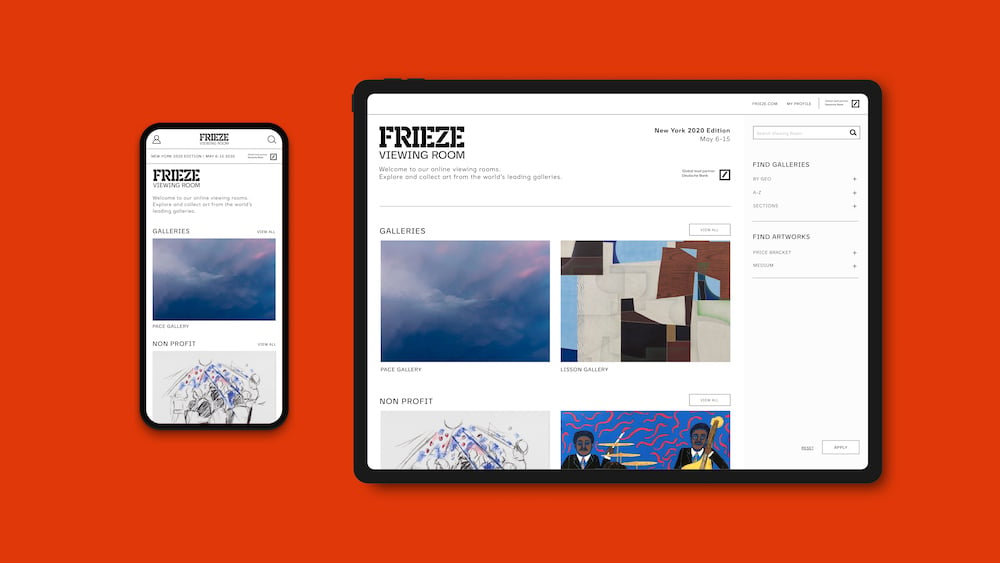

Frieze New York. Image courtesy of Frieze.

During test runs before the official launch, Frieze organizers worked closely with roughly ten galleries who experimented with uploading works in order to see what worked and what didn’t. “People are being thoughtful about what kind of works they should present,” Randolph says. Galleries will begin to upload work to the platform today; Frieze is encouraging them to include prices, but will not require it. The fair will not disclose names or contact information of anyone who enters the room to galleries unless visitors inquire abut a work on view.

Frieze is one of many art-market players working to beef up its online offerings in recent months. Within the past week alone, mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth unveiled ambitious plans for a new virtual reality platform and both Lisson Gallery and Massimo De Carlo announced plans to launch their own e-commerce VR platforms. Art Basel Hong Kong launched an online viewing room—to mixed success—in lieu of its physical fair in March. (Both Frieze and Art Basel offered exhibitors the chance to participate in the first iteration for free, although ABHK refunded dealers 75 percent of their booth fees, while Frieze provided full refunds.) If the Art Basel experiment is any indication, Frieze will face the test of whether its platform can funnel sales to smaller galleries as effectively as larger ones.

Randolph concedes the learning curve has been steep, noting “the urgency of the cancellation of Frieze New York changed the way we were thinking” about what was initially intended as a complement to the fair. “I think museums are having similar questions about how everything can translate from the physical experience. Conceptually and ideologically, I don’t think that’s possible. Nor do I or Frieze organizers think that an online viewing room should be a replacement for a fair or for all of us being together physically in one space and experiencing art in person.”

Still, the platform seeks to feature some of Frieze New York’s most highly anticipated projects, including “Spotlight,” a section dedicated to pioneering figures of the 20th century curated by Drawing Center executive director Laura Hoptman. Also available for browsing is “Diálogos,” a celebration of Latin American, Latino, Latinx artists organized by the leadership of El Museo del Barrio. Meanwhile, Julie Rodrigues Widholm, director of the DePaul Art Museum, has organized “Chicago Tribute,” an homage to the pioneering female artists of Chicago.

“This first iteration of the platform,” Randolph says, “has become a digital version of Frieze New York.”